UNCOMMONLY DANGEROUS: ERIC AMBLER ON TV

by Tise Vahimagi

The early literature of Eric Ambler belongs with such contemporaries as Graham Greene and Geoffrey Household: novels which plausibly construct their dark and ominous prophesies of quiet disaster and which find the power game, as played out by ordinary people on intercontinental trains and across shifting frontiers, more imaginatively stimulating than the one-man antics of the post-Ian Fleming era.

Above all, Ambler’s novels have that air of confident enjoyment in the game they are playing which is so easily conveyed to the reader: his works are entertainments, in Greene’s sense of the word, and, undeniably, intelligent ones.

It is a truism that Ambler was the founding father of the modern political thriller, the writer who brought the genre to maturity in the 1930s. In just six novels, from The Dark Frontier in 1936 to Journey into Fear, 1940, he created the distinctive form that was to have a seminal influence on all writers in the genre.

In the late 1930s, he had strong anti-fascist leanings and his stories reflected the political tensions of the time, when Europe was about to explode. Before he rewrote the conventions of the spy thriller, the genre was epitomised by Sapper’s thuggish Bulldog Drummond and Buchan’s Hannay, officer-class heroes with little more than a gung-ho approach to life and its problems.

Moreover, detective stories of the day (by the likes of Dorothy L. Sayers) were considered respectable; thrillers in the former vein were not. Happily, Ambler changed all that.

His heroes were genuinely ordinary people, amateurs of a kind closer to Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden. They stumbled into complex situations, where they had to make tough choices under pressure. A romantic sense of Ruritania gave way to a more precise Italy, France and Turkey preparing for a second world war.

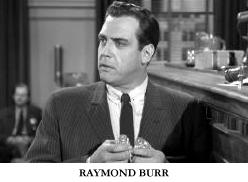

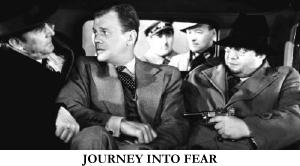

As we know, four of his six pre-war novels became films (of varying merit). The Mask of Dimitrios (Warner Bros, 1944; from A Coffin for Dimitrios) and Journey into Fear (RKO, 1943) remain consistently enjoyable with a nice tangle of mystery and suspense.

Background to Danger (WB, 1943; from Uncommon Danger) provides a suitably menacing, violent atmosphere for Greenstreet and Lorre to display their familiar brand of icy unpleasantness.

The British production, Hotel Reserve (RKO, 1944; from Epitaph for a Spy), already reviewed and discussed in detail here, looked better (thanks to camera operator Arthur Ibbetson) than it perhaps deserved.

For the most part, the television work of an author (whether as adaptations of their work or as original teleplays) is generally regarded — when it is regarded at all — as less than worthy of interest. My view is that all of an author’s work is of interest. The TV representations of Ambler’s work are, admittedly, more often less-than-rewarding but are still worthy of examination.

His earliest work to appear in a television translation was the espionage thriller Epitaph for a Spy (1953), a BBC-produced six-part serial dramatised by Giles Cooper and featuring Peter Cushing as the innocent-in-a-spot teacher Josef Vadassy. The following year, CBS adapted the story (drawing on the services of three writers) for their anthology series Climax! (CBS, 1954-58), starring Edward G. Robinson as the frightened, bumbling character.

BBC-TV returned to Ambler’s story again in 1963 for a four-part serial (dramatised by the usually dependable Elaine Morgan). Unfortunately, the producers, seemingly lacking confidence in the 1938 work, decided to condense the story into four instalments and, of all things, update it to the 1960s (changing nationalities, providing new motives and readjusting relationships). It is indeed unfortunate that the 1953 BBC version no longer exists; it should be considered a small mercy that there is no sign of a recording of the 1963 ‘satire’.

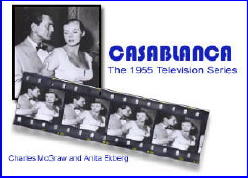

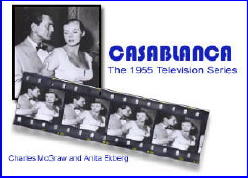

Although A Coffin for Dimitrios was not afforded an adaptation for television as such, the basic plot turned up as “Satan’s Veil” (1956), an episode of the Warner Bros. TV drama Casablanca (ABC, 1955-56).

The storyline (presumably a Warner property since their 1944 The Mask of Dimitrios) was reworked in the form of an adventuress (the sultry Rossana Rory) trying to conceal the details of her faked death from Charles McGraw’s hard-boiled Rick.

Considering that other WB works were given a small-screen adaptation (“Casablanca”, in 1955; “Mildred Pierce”, 1956; “To Have and Have Not”, 1957, etc.) via the adventurous Lux Video Theatre (CBS/NBC, 1950-57), one wonders why the perfect-for-TV Dimitrios was overlooked.

The other Climax! presentation was a lamentable “Journey into Fear” (1956) with a quivering John Forsythe as a terrified-out-of-his-wits American engineer whose life is endangered in Istanbul and then shipboard to Genoa by ever-present assassins. Hitchcock television regular James P. Cavanagh adapted Ambler’s 1940 novel.

The Schirmer Inheritance (ITV, 1957), involving a New York attorney’s search for the rightful heir to a $4,000,000 inheritance, was adapted into a six-part serial by Kenneth Hyde for Britain’s ABC-TV company. Not so much a wary passage through post-war Europe (in the Greene/Third Man vein) as a gallery of suspicious figures in a rather over-talky journey to a bandits’ lair on the Yugoslav-Greek border.

Ambler moved to Hollywood in the late 1950s and, in 1958, married long-time Hitchcock collaborator producer-writer Joan Harrison, who was at that time producing the Alfred Hitchcock Presents (CBS/NBC, 1955-62) and Suspicion (NBC, 1957-59) anthologies.

For the latter collection (where he met Harrison), Ambler wrote the soft mystery “The Eye of Truth” (1958) featuring Joseph Cotton as a blackmailed corrupt attorney who’s trying to cover up some incriminating documents. In 1962 he was brought on-board the Alfred Hitchcock Presents series to adapt a Nicholas Monsarrat short story as the episode “Act of Faith” (1962) in which an aspiring author seeks finance from a successful novelist, with unexpected repercussions. (This was Ambler’s second adaptation of a Monsarrat work; the first, the screenplay for the 1953 wartime drama The Cruel Sea, earned him an Oscar nomination.)

Perhaps his most curious and direct television contribution was as creator of the mystery series Checkmate (CBS, 1960-62), an often satisfying who’s-going-to-do-it drama involving a trio of San Francisco private investigators: their job, and the series’ hook, being to prevent crimes before they happen.

Although it was intimated at the series’ launch that Ambler himself would be contributing original stories, the series did employ the tantalising talents of many respected crime-mystery writers, including Leigh Brackett, Jonathan Latimer and William P. McGivern. The hugely enjoyable “The Terror from the East” (1961) episode (written by Harold Clements), with a highly suspicious, shambling Charles Laughton as a visiting missionary from China, has our heroes running in circles like hypnotised rabbits.

A later, similarly formatted series, The Most Deadly Game (ABC, 1970-71), created by Mort Fine and David Friedkin (for Aaron Spelling Productions), featured three criminologists who, rather than preventing crimes, engaged in solving offbeat whodunits. Since Joan Harrison was one of the series’ producers (along with Fine & Friedkin) one can be less than surprised by the similarity.

Although some modern sources have credited Ambler with the development of The Most Deadly Game, Fine and Friedkin are the only ones to receive a ‘created by’ credit.

An additional point of interest: a co-writer credit for the episode “Model for Murder” (1970) goes to the fascinating but elusive Elick Moll who, in collaboration with Frank Partos, wrote the screenplay for the hauntingly Woolrichian Night Without Sleep (20th Fox, 1952), based on Moll’s original treatment (and published as a novel in 1951).

For Alcoa Premiere’s “Pattern of Guilt” (1962), Ambler, as producer of the episode, hired Helen Nielsen to compose an original teleplay for what may have been a proposed series’ pilot episode. The story involved Ray Milland as a reporter who is assigned to cover a series of murders, all spinsters, where related clues are found at each murder scene. Little seems known about this one; why Ambler suddenly became a producer (if in fact so), was it actually intended to spin-off a Milland-as-reporter series?

Following up the association with Aaron Spelling Productions, Ambler wrote and Harrison produced Love, Hate, Love (ABC, 1971), an annoyingly tedious TV movie thriller starring Ryan O’Neal and Lesley Warren as a couple stalked by Warren’s psychotic ex-boyfriend (Peter Haskell).

The next of Ambler’s spy stories to be adapted for the small screen was the four-part A Quiet Conspiracy (ITV, 1989). Taken from his 1969 novel The Intercom Conspiracy, the post-le Carré plot follows former journalist Joss Ackland and his daughter Sarah Winman as they stumble about in an international conspiracy involving a secret NATO spy satellite. The red herring fishery was worked overtime, thanks to producer Anglia TV’s co-production casting of various, unfamiliar European actors.

With The Care of Time (ITV,1990), another made-for-TV film (Anglia TV), adapted from Ambler’s 1981 novel, the central character, an American ghost writer (a baffled Michael Brandon), is an outsider who is drawn into an overly-complicated web of international intrigue.

The puzzling plotting and colourful scenery moves (totters, at times) from Pennsylvania, across Europe to the Austrian Alps, collecting Christopher Lee’s political fixer, who’s ducking his enemies, and his attractive body-guard (Yolanda Vazquez) along the way. An ambitious TV film with a reach that was greater than its grasp.

A couple of Footnotes: one of relevance to the above television work; the other because it’s an irresistible connection.

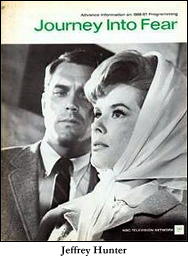

(I) In 1965, US trade journals began making brief, intriguing references to the production of a pilot episode (“The Seller’s Market”), written by Ambler, for a proposed espionage series called Journey Into Fear for NBC; the episodes would revolve around star Jeffrey Hunter as a scientist who is drawn into working for the CIA.

Completed (and an hour in length), the series was rejected by the network and the pilot episode was despatched to the vaults. Perhaps the partnership of Ambler and the 1960s Spy Boom would have been an awkward one (he had a dislike for master-villains, pseudo-scientific gadgets and the general paraphernalia that characterised the 1960s spy genre), but the possibilities still fire the imagination.

For a fuller report on this unsold series, check this link for Glenn Mosley’s (University of Idaho) absorbing survey.

(II) Geoffrey Household merits some reference here, not only because Ambler wrote the screenplay for Rough Shoot (1953; aka Shoot First), based on his 1951 novel, but that Household’s espionage/adventure characters belong to the same fold as Ambler’s victims of circumstance.

His most famous work is of course Rogue Male (1939), becoming the much praised Fritz Lang film Man Hunt in 1941 and, in 1976, an equally commendable TV film starring Peter O’Toole. Another TV film, Deadly Harvest (1972), was made from his 1961 novel Watcher in the Shadows.

Two early Suspense (CBS, 1949-54) episodes based on Household stories (“Death Drum”, 29 Jan 1952; “Woman in Love”, 26 Aug 1952) can be viewed on the Internet Archive. (Follow the links provided.)

Eric Ambler Television:

1. Epitaph for a Spy (serial; BBC, 14 March-18 Apr 1953; 6 x half-hour). Producer/Director: Stephen Harrison. Scr: Giles Cooper, from 1938 novel. Cast: Peter Cushing (as Vadassy), Ferdy Mayne, Warren Stanhope, Joan Winmill.

2. “Epitaph for a Spy” / Climax! (CBS, 9 Dec 1954). Dir: Allen Reisner. Scr: Donald S. Sanford, David Friedkin, from Ambler novel. Cast: Edward G. Robinson (Vadassy), Melville Cooper, Marjorie Lord, Dave O’Brien.

3. “Satan’s Veil” / Casablanca (ABC, 31 Jan 1956). Dir: Alvin Ganzer. Scr: Norman Lessing, Nelson Gidding, from ‘story’ by Ambler. Cast: Charles McGraw, Marcel Dalio, Rossana Rory, Dan Seymour.

4. “Journey into Fear” / Climax! (CBS, 11 Oct 1956). Dir: Jack Smight. Scr: James P. Cavanagh, from 1940 novel. Cast: John Forsythe (as Graham Johnson), Eva Gabor, Arnold Moss, Anthony Dexter.

5. The Schirmer Inheritance (serial; ITV, 3 Aug-7 Sept 1957; 6 x half-hour). Prod: Stuart Latham. Dir: Philip Dale. Scr: Kenneth Hyde, from 1953 novel. Cast: William Sylvester, Vera Fusek, Jefferson Clifford.

6. “The Eye of Truth” / Suspicion (NBC, 17 Mar 1958). Prod: Alfred Hitchcock. Dir: Robert Stevens. Scr: Eric Ambler. Cast: Joseph Cotton, George Peppard, Leora Dana, Philip Van Zandt.

7. Checkmate (series; CBS, 1960-62). Created by Eric Ambler. Regular Cast: Anthony George (as Don Corey), Doug McClure (Jed Sills), Sebastian Cabot (Dr. Carl Hyatt).

8. “Pattern of Guilt” / Alcoa Premiere (ABC, 9 Jan 1962). Prod: Eric Ambler. Dir: Bernard Girard. Scr: Helen Nielsen. Cast: Ray Milland, Myron McCormick, Joanna Moore, Olive Carey.

9. “Act of Faith” / Alfred Hitchcock Presents (NBC, 10 Apr 1962). Dir: Bernard Girard. Scr: Eric Ambler, based on a story by Nicholas Monsarrat. Cast: George Grizzard, Dennis King, Florence MacMichael, Jeno Mate.

10. Epitaph for a Spy (serial; BBC, 19 May-9 Jun 1963; 4 x half-hour). Prod/Dir: Dorothea Brooking. Scr: Elaine Morgan, from Ambler novel. Cast: Colin Jeavons (Vadassy), Burnell Tucker, Janet McIntire.

11. Love, Hate, Love (TV film; ABC, 9 Feb 1971). Dir: George McCowan. Scr: Eric Ambler, based on story by Ambler, Robert Summerfield. Cast: Ryan O’Neal, Lesley Ann Warren, Peter Haskell, Henry Jones.

12. A Quiet Conspiracy (serial; ITV, 24 Feb-17 Mar 1989; 4 x hour). Prod: John Rosenberg. Dir: John Gorrie. Scr: Alick Rowe, from 1969 novel The Intercom Conspiracy. Cast: Joss Ackland (as Theodore Carter), Sarah Winman, Hartmut Becker.

13. The Care of Time (TV film; ITV, 26 Aug 1990). Dir: John Davies. Scr: Alan Seymour, from Ambler novel. Cast: Christopher Lee, Yolanda Vazquez, Ian Hogg, Michael Brandon.

Footnote: “Seller’s Market” / Journey into Fear (1966 pilot episode; not transmitted). Prod: Joan Harrison. Dir: Robert Stevens. Scr: Eric Ambler. Cast: Jeffrey Hunter.

EDITORIAL COMMENT. Eric Ambler was born 28 June 1909, so next month will mark the 100th anniversary of his birth. We apologize for jumping the gun by a few days, but we welcome the opportunity to toast here and now one of the greatest spymasters of all time.

![BURN NOTICE [USA]](https://mysteryfile.com/blogImg509/BN-Four.jpg)

![BURN NOTICE [USA]](https://mysteryfile.com/blogImg509/BN-Pair.jpg)

![BURN NOTICE [USA]](https://mysteryfile.com/blogImg509/BN-GA.jpg)