Fri 7 Jun 2024

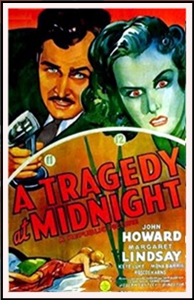

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: A TRAGEDY AT MIDNIGHT (1942).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[4] Comments

A TRAGEDY AT MIDNIGHT. Republic Pictures, 1942) John Howard, Margaret Lindsey, Keye Luke, Mona Barrie, Roscoe Karns, Miles Mande.r Screenplay by Isabel Dawn, based on a story by Hal Hudson and Sam Duncan. Directed by Joseph Santley. Currently streaming on YouTube (added below, but see Comment #1).

Radio detective Greg Sherman (John Howard) is roundly disliked by the police who he harasses with his weekly program solving crimes while they twiddle their thumbs, so when he wakes up to find a murdered woman in the twin bed in the borrowed apartment of Dr. and Mrs. Wilton (Miles Mander and Mona Barrie) where his new wife Beth (Margaret Lindsey) should be, while their apartment across the hall is being painted, it looks bad, and when Lt. Cassidy (Roscoe Karns) shows up and arrests him, it looks even worse.

Luckily for Sherman, with a little help from his wife and houseboy Ah Foo (Keye Luke), he quickly escapes, but now he is on the run not even knowing the name of the murder victim.

Obviously modeled on The Thin Man, and despite the stereotyped Chinese houseboy who speaks in pidgin English (but luckily has brains and knows judo) this film from Republic Pictures moves fast and has a decent mystery at its heart, as Sherman and his attractive wife discover the dead woman had two names, two apartments, and two lovers, one a club owning gangster.

As murder and circumstance eliminates their best suspects Sherman races to find the solution and manage to make the deadline for his next broadcast where he has to produce the killer.

Howard and Lindsey make for an attractive minor substitute for William Powell and Myrna Loy and have some natural presence playing off of each other. The suspects are the usual lot. and there are a number of decent red herrings along the way before Howard closes in on the real killer on the air.

Of course there are holes in the plot. and you probably don’t want to think too much about it, but the solution is satisfying and one of those “that was obvious” endings that aren’t really obvious until you actually hear them explained.

The whole stereotyped Chinese houseboy business is. as you might suspect, offensive, but frankly Luke seems to be playing it tongue ’n cheek and brings such energy to the part, it’s hard to dwell on the injustice. He was an actor who was invariably better than the material he was given. It’s hard to imagine why the pidgin English though, considering his years as the thoroughly American Jimmie Chan. He’s at least integral to the plot and not just comedy relief.

There’s nothing new here, but it is done with energy and at least some thought to the mystery and not merely the comedy and quick patter. As a B, it does exactly what it aims to, which is worth commending in any film.