REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

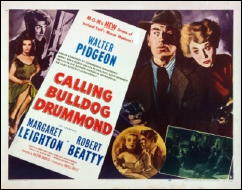

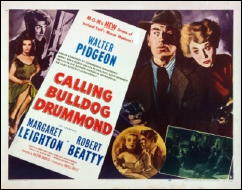

CALLING BULLDOG DRUMMOND. MGM, UK, 1951. Walter Pidgeon (Major Hugh ‘Bulldog’ Drummond), Margaret Leighton, Robert Beatty, David Tomlinson, Peggy Evans, Charles Victor. Based on a story by Gerard Fairlie. Director: Victor Saville.

Back in the late 60s, when I decided I wanted to live a life of adventure, I was quite taken with a gaudy Universal James-Bond-Rip-Off called Deadlier Than the Male, with Richard Johnson as Bulldog Drummond and Nigel Greene as bis arch-foe Peterson. Elke Sommer and Sylva Koscina were in it too, as scenery.

I liked the gaudy color, kinky violence, and general comic-book look of the thing. Don’t try to catch it on television, though, because it was castrated for Network Release and to my knowledge has never been restored. (Yeah, like someone would take the time to put all the sex and violence back in to this.)

Anyway, I tried the Drummond books and didn’t care much for the character in them at all, as he seemed something of a blow-hard bigot. Always liked the Drummond movies, though, including a B series from Paramount with John Howard, John Barrymore and lots of colorful baddies. And of course there was the great Colman film of ’29 which I viewed a wile back.

So I was sort of looking forward to Calling B. D. and was disappointed. The plot features a gang of crooks who operate in Military Style, prompting Scotland Yard to call Colonel Drummond out of retirement because of his military experience.

I don’t know about you, but I have a little trouble swallowing the notion that England in the 50s suffered from a shortage of men with Military experience, and the Surprise Bad Guy is unfortunately portrayed by an actor who later became mildly famous, so his off-screen voice tips us off immediately.

Add to this that Pidgeon seems to have taken his Dull Pills just prior to filming, and you have a very quiet movie indeed.

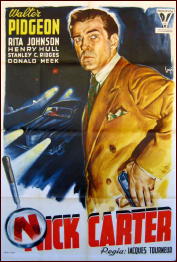

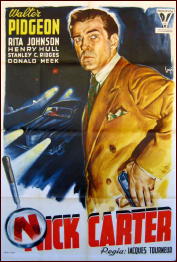

NICK CARTER, MASTER DETECTIVE. MGM, 1939. Walter Pidgeon (Nick Carter), Rita Johnson, Henry Hull, Stanley Ridges, Doctor Frankton, Donald Meek (Bartholomew), Milburn Stone. Director: Jacques Tourneur.

PHANTOM RAIDERS. MGM, 1940. Walter Pidgeon (Nick Carter), Donald Meek (Bartholomew), Joseph Schildkraut, Florence Rice, Nat Pendleton, John Carroll. Director: Jacques Tourneur.

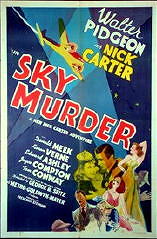

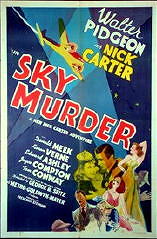

SKY MURDER. MGM, 1940. Walter Pidgeon (Nick Carter), Donald Meek (Bartholomew), Kaaren Verne, Edward Ashley, Joyce Compton, Tom Conway. Director: George B. Seitz.

Pidgeon came off much better in a series of “B’s” from MGM in the late ’30s centered around a character called Nick Carter, though for all the care they took to recreate the old Dime Novels, they might as well have called him The Saint or Bulldog Drumond or V.I. Warshawski. Nick Carter Master Detective, Phantom Raiders and Sky Murder are all quite fun and you should see them if you ever get a chance.

With that sonorous voice of his, Pidgeon always sounded like Gregory Peck’s older brother, but these films play against his tendency to stodginess and come out very light and fluffy. The first two were stylishly directed by Jacques Tourneur, but the best thing in them is the Comedy Relief played by Donald Meek.

The comical sidekick was as much a fixture of the B-Mystery series as he was in the B western, but Meek and the writers here lift the concept to dizzying heights. His Bartholomew is not the standard dim-witted clod of most B-Mysteries: he’s a dangerous madman, given to melodramatic fantasies and theatrical outbursts of classic,dimensions.

He looks like the kind of guy who might bite you on the leg for no good reason at all, and given the chance to play something besides a timid fuddy-duddy, Meek indulges himself with a flair for wild-eyed comedy I’d never suspected in him. He is that rarity, a Comic Relief you actually look forward to seeing, and be adds immeasurably to the films. Catch these if you can.

Editorial Comment: Mike Grost has some interesting things to say about the two Nick Carter films directed by Jacques Tourneur. Check out his website here.