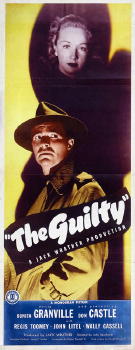

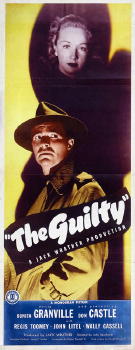

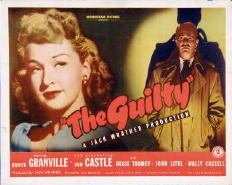

THE GUILTY. Monogram, 1947. Bonita Granville, Don Castle, Wally Cassell, Regis Toomey, John Litel. Screenplay: Robert Presnell Sr., based on a story by Cornell Woolrich. Producer: Jack Wrather. Director: John Reinhardt.

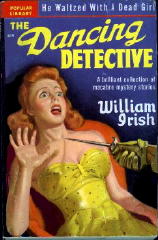

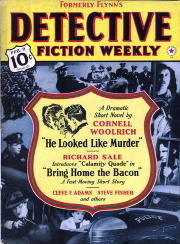

[WILLIAM IRISH – “Two Fellows in a Furnished Room.” Long novelette included in The Dancing Detective, Lippincott, hardcover, 1946; Popular Library 309, ppbk, January 1951. Originally published as “He Looked Like Murder,” as by Cornell Woolrich, Detective Fiction Weekly, 8 February 1941.]

Some of the books on noir films like this movie quite a bit, but if I were writing one, the one I’d write wouldn’t be one of them. It’s a noir film all right – how could it not be, based as it is one of the originators of noir fiction, Cornell Woolrich?

Poor production values, for one possibility, is the answer, and even more poorly conceived changes and/or additions to the story, both of which, in my opinion, occurred in the making of The Guilty.

Woolrich’s story is long but compact, complete in itself, and full of his usual “things gone wrong in an everyday world” motif. One fellow of two sharing a room together asks the other to stay away for a couple of hours while his girl friend comes over. After Stewart Carr, the one who was asked to leave, returns – he’s also the one telling the story – the girl’s mother calls, asking where her daughter is.

She’s disappeared, and when Carr’s roommate John Dixon begins to act more and more suspiciously, Carr tries to stay on his side, but he begins to find it more and more difficult to do so. This is the kind of mess you get into, suggests Woolrich in his role of author, when you start to hide things you needn’t, you panic, and all you end up doing is making the mess even worse.

Fate, at nearly the last minute, steps in, however, before Dixon is picked up by the police and (more than likely) railroaded off to the death house. The friendship is over, of course, even though things worked out OK in the end.

Woolrich’s stories are almost always a little over the top, some more than others, and this is one of them. It’s a little too short for a movie, even one only 71 minutes long, so of course some additional material has to be added.

Some of what was done is understandable, or at least you can figure out why. I mentioned in the opening credits that Jack Wrather was the producer. In 1947, the same year that The Guilty was made, he and Bonita Granville, the star of the film, were married. And any story in which the only major female role is someone who dies in the first chapter is hardly a part for any leading lady to consider, married to the producer or not.

Solution? Double the part by giving the girl who dies (Linda) a twin sister (Estelle) who’s as manipulative-of-men bad as the dead girl was good. More, to complicate matters – none of which appeared in the original story, of course – make Carr fall for the bad girl after she was dumped by the roommate for the good girl, who’s the one who died, with (as in the story) the roommate strongly suspected of doing the killing.

I don’t recall ever seeing it, but in 1946, the year before The Guilty was made, Olivia De Havilland played a similar pair of good and bad twins in The Dark Mirror. Apparently one takes ideas wherever one can get them. Similar story lines probably occurred even before that, and probably several times over.

In any case, it takes a while to sort things out – luckily the girls meet on the screen together only once, and after all, Linda leaves the film soon after anyway. What seemed awkward to me at the beginning, though, was the framing device of Carr coming to the bar around the corner from the room where all this happened, some six months later, waiting for a girl to show up – we don’t know who, of course, at the beginning.

The purpose? To help extend the ending of the novelette to include a newly devised one. A twist, in other words, as to who the real killer was.

And here’s where everything really does goes wrong. Retrofitting a new ending to a detective story – and that is exactly what this is – one in which the clues are already pointing to one person – simply can’t be done without a complete rewrite, in which case you may as well write a brand new screenplay and leave Woolrich’s tale out of it altogether. What’s done is done, but even so, Pfui is what I say to the new ending.

One other thing. Jack Wrather is described as an oil millionaire, but he certainly didn’t sink any money into this movie. (In 1954 he bought the rights to The Lone Ranger, and later on Sergeant Preston and Lassie, eventually producing all three as television series.)

But in 1947 the sets in The Guilty are bare bones to the max. Some observers suggest that this only heightens the noir mood of the film, emphasizing the bleakness of the characters’ fates.

To some extent I can see what they’re saying, but when all you can see in the film are little more than solid but completely stagey sets, all I can say is another Pfui. (Regretfully. I do want to make that clear.)

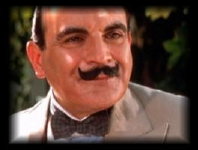

I guess I was wrong; there were two other things I meant to add a moment ago, not just one. Bonita Granville was only 24 when she made this movie, but she’d already had a long career behind her in making films. She was, of course, most well known for the four movies she made in her teens as Nancy Drew, girl detective.

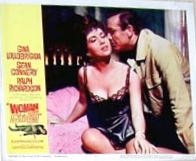

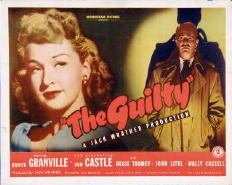

Girlishly buoyant and full of enthusiasm in the role, one she may have been perfect for, if she had not married Wrather, she may have had a even longer career playing “bad” girls in noir films such as The Guilty. I don’t believe this photo I found of her is necessarily related to her role in that movie, but if not, it’s close enough, and I think it will show you more what I mean than I can say in words.

Unless one of the words is Huzzah!