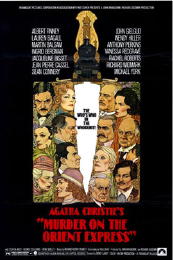

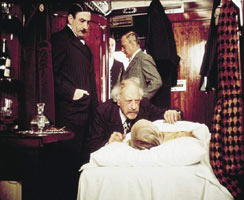

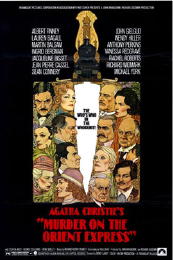

MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS. Paramount, 1974. Albert Finney, Lauren Bacall, Martin Balsam, Ingrid Bergman, Jacqueline Bisset, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Sean Connery, John Gielgud, Wendy Hiller, Anthony Perkins, Denis Quilley, Vanessa Redgrave, Rachel Roberts, Richard Widmark, Michael York, George Coulouris. Directed by Sidney Lumet.

They don’t make movies with all-star casts like this anymore, and maybe for a couple of good reasons. First of all, I don’t think you can convince me that in this modern, contemporary era of movie-making there are enough stars with the on-screen magnitude to match the ones you see above to make a film like this today.

And secondly — and here’s a point in favor of the small-scale modern day casting — having too many stars can sometimes detract from the story and divert the audience’s attention away from it.

Your eye sees the star, in other words, and you don’t see the character. The actors play roles rather than disappearing into parts. It probably can’t be helped in extravaganzas like this, but — and this is a rather subtle “but” — in thinking it over afterward, in terms of this grand, elaborate production of one of Agatha Christie’s masterpieces of deductive detective fiction, it may have even helped.

I’m sorry if I’m being cryptic here, but if you’ve seen the movie, it’s possible that you very well know what I mean.

Before going on, and perhaps I shouldn’t admit it, but last night was the first time I’ve seen the film. I don’t know how I missed it when it first came out, or if I did, I’ve forgotten it completely, and I hardly believe I could have done that.

So in what follows, you’re getting my opinion as it’s just been formed, with a “mature” eye, and not by the eye of a 30-something. (Notice that I put “mature” in quotes, keeping in mind that being old enough to collect Social Security does not necessarily imply mature.)

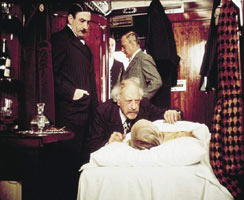

Albert Finney as Poirot. Other than the later BBC productions with David Suchet, and I regret to say that I have seen only one of them, I think too many actors play Poirot as a comic character, what with his large assortment of eccentric mannerisms and sometimes faulty English.

In the opening minutes of Orient Express, I could feel myself cringing at the anticipation of yet another performance played for laughs, but when Poirot gets down the business of solving the murder of a notorious crime figure traveling incognito on the train heading from Istanbul to England, he is exactly that. Down to business.

The final scene, confronting the group of passengers who are the only suspects on the snowbound Express, takes at least 20 minutes of intense revelation, going over the clues and the deductions the Belgian detective made from them.

I should have timed how long the scene actually takes. I know that I’ve read somewhere that filming the scene, in the restricted confines of the dining car, took several days. I can believe it.

Luckily the flashback scenes, with the crime being reconstructed, piece by piece, break up the sequence of talking heads in a rhythm that slowly builds and builds upon itself.

Even so, the lack of action that this approach entails means that there’s hardly action enough to suit modern day audiences, or am I only being cynical again?

Finney is probably the only actor to play a detective concerned with clues and not the third-degree in back rooms to have been nominated for an Oscar, but on second thought, without going to check on it, there’s a finite chance that I’m wrong about that.

But as for his performance, as regarded by others, according to IMDB: “An 84-year-old Agatha Christie attended the movie premiere in November of 1974. It was the only film adaptation in her lifetime that she was completely satisfied with. In particular, she felt that Albert Finney’s performance came closest to her idea of Poirot. She died fourteen months later, on January 12, 1976.”

If she was pleased, then how I dare say anything otherwise? I can’t, and I don’t. As for the rest of the cast, while I enjoyed Lauren Bacall’s role as the the outspoken (and never stopping) American tourist more, it was Ingrid Bergman who actually won an Oscar, for her much briefer part as a semi-demented Swedish missionary lady. A good performance, even a very good one, but I have a feeling it may have been a slow year for the Academy.

Should I say something about the plot, more than I have so far? Perhaps not, but this is a tour de force of some magnitude, based as it was on the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby. The book was first published in England in 1934, and as Murder in the Calais Coach in the US later the same year.

Before the movie was shown on Turner Classic Movies, which is where I taped it from, the host, Robert Osbourne, pointed out that it took 40 years before the movie could pass the Movie Code. If you know the story, you will know why, and once again, that is all I am able to say about that.

In terms of the detective work — well, let me tell you a story. Back when I was young, and maybe even younger than that, I decided that the next Agatha Christie novel I read, by golly I was going to take detailed notes and actually solve the murder myself. Well I did, and I didn’t.

I was so upset at how the crime was committed and who did it that I literally threw the book across the room. Carefully, of course.

The movie was extremely successful. Albert Finney was asked, but he turned down the opportunity to play Poirot again. Peter Ustinov, chosen in his place, played the part in Death on the Nile (1978), Evil Under the Sun (1982), and Appointment with Death (1988).

He also appeared in three made-for-TV films: Thirteen at Dinner (1985), Dead Man’s Folly (1986), and Murder in Three Acts (1986). From what I remember — I haven’t seen any of these films in a while — I mostly regretted Ustinov in the role. Albert Finney, I think I could have gotten used to, now that I’ve had some time to think it over, and even more so as time goes on.

[UPDATE] 03-11-07. Looking back on my comments above, I regret not saying more about the opening terminal scene with the passengers boarding the train in the Istanbul station. Beautifully photographed, highly choreographed, and true to the period, it is nearly worth the price of admission in itself.

Before I say anything more about it, though, I’m going to have to go back and watch it again. It was far too “visual” the first time, but for me, opening scenes often are. I find myself trying to make sure I’m not missing anything of the story while, at the same time, I’m struggling to take in everything there is to see. Delightful!

[A little bit later.] It was too hard to resist. I’ve just ordered the DVD from Amazon, the version with director Sidney Lumet’s commentary on “The Making of the Movie,” and who should know more how the movie was made than he?