Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

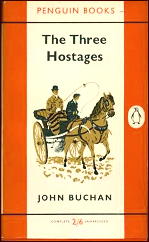

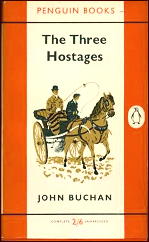

JOHN BUCHAN – The Three Hostages. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1924. Houghton Mifflin, US, hc, 1924. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback, including Bantam #31, US, pb, April 1946; Penguin, UK, pb in dj, 1955 (both shown). TV movie: BBC, 1977, with Barry Foster & Diana Quick as Richard & Mary Hannay; director: Clive Donner.

The Three Hostages is the fourth novel by John Buchan in the series of novels featuring Richard Hannay. Hannay made his debut in The Thirty-Nine Steps as a South African in his late thirties living in England on the eve of WWI, where he is drawn into a conspiracy and finds himself on the run from the police and the conspirators. He finally meets Sir Walter Bullivant, who is something in the British Secret Service, and foils a German plot to cripple the British fleet.

In the sequel, Greenmantle, Hannay is a Major in the army recalled from the front by Bullivant to take on a dangerous mission to stop the Germans from exploiting a prophecy involving a Turkish leader that could open a new front in the European war. In this book we first meet American agent John S. Blenkiron, South African voortrekker Peter Piennar, and Hannay’s best friend, the Lawrence of Arabian style mystic, warrior, and scholar Sandy Abuthnot, Lord Clanroyden.

In Mr. Standfast, Hannay is now a Brigadier General, again called back from the front to face the German spy master who eluded him in the first two books. He meets his wife to be, Mary, and again teams with Sandy, Blenkiron, and Peter Piennar, and RAF pilot Archie Roylance, who will feature in later Buchan novels, John McNab, Huntingtower, and The Courts of Morning.

The Three Hostages takes place five years after Mr. Standfast. Hannay, now Sir Richard, is comfortably retired with his wife Mary, and their infant son Peter John. The last thing Hannay wants is an adventure, but when he is approached by a man whose son has been kidnapped, but who cannot go to the police, he is reluctantly drawn back into action. With the help of Sandy Arbuthnot he decyphers a mysterious Latin quote, and that leads him to the charismatic upcoming political figure Dominic Medina, a man of considerable charm and rare hypnotic power.

Medina is ambitious and dangerous, and soon Hannay is caught in the middle of a power grab that involves kidnapping the children and loved ones of important figures and using the dark and possibly mystic hypnotic influence Medina has over the victims to control their loved ones.

Soon Hannay, Sandy, Mary, and a small group are racing across the continent from London’s night life to a remote farm in Norway to free the victims. Hannay foils Medina and the angered Medina sets out to stalk him in the rough country of Hannay’s estate. Medina dies horribly and Hannay is rescued by his wife and groundskeeper.

That’s a fairly simple description of what is one of the best and most influential thrillers ever written. Fully half the books under the thriller category fall under Buchan’s spell, and a whole school of writers like Geoffrey Household, Hammond Innes, Gavin Lyall, Desmond Bagley, Allan MacKinnon, Geoffrey Jenkins, Victor Canning, and more are his direct descendants.

In addition Buchan is generally credited with having created the modern spy novel with his 1910 Strand Magazine novella, “The Power House,” in which he predicted the rise of Fascism in the 20th Century.

In addition he moved the setting of the thriller from the wilds to the heart of the urban world when his hero, Edward Leithen first recognizes, in the middle of busy Piccadilly Circus, that the only thing protecting him is the thin veneer of civilization.

In The Thirty-Nine Steps Buchan carries it further by setting the pattern of the innocent man caught up in circumstances that he can’t control that would be the theme of writers such as Graham Greene and Eric Ambler (albeit with far more complex and less sportsman like heroes than Richard Hannay), and filmakers like Alfred Hitchcock and Fritz Lang. The novel of chase, pursuit, conspiracy, and intrigue comes from Buchan’s work. He is what O. F. Snelling once called, ‘the onlie beggeter.’

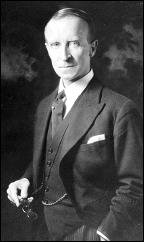

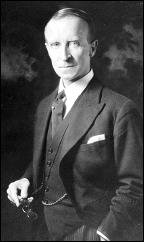

Buchan is unique among writers of popular fiction in that his influence in the real world is even more important than that in fiction. The son of a lower middle class Scottish family he became a noted scholar, historian, biographer, and political figure. He knew and influenced the most important figures of the early 20th Century from Lawrence of Arabia to Bernard Baruch.

A Member of Parliament he was later given the title of first Baron of Tweedsmuir, in 1935 he was given the difficult post of Governor General of Canada, his assignment to repair the shaky state of affairs between Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King and London and King and the United States, assuring that in any coming conflict Great Britain could count on its most important Commonwealth partner.

Working tirelessly, he died of exhaustion in 1940, he charmed King, reconciled him with London, reconciled him with FDR and the United States, and had no small influence in the eventual Lend Lease program that kept England alive in the early days of WWII before America entered the war. Time magazine had called him one of the most influential men of the age when they featured him on the cover. When he died he was mourned by statesmen, commoners, and kings.

That he was also a storyteller whose tales of horror inspired H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, a biographer of note, a noted historical novelist, a writer of popular thrillers (he preferred the term ‘shockers’), and a scholar is a mark of how great his talents were. Two of the books on John F. Kennedy’s famous list of this ten favorite books were by Buchan, his memoir Pilgrim’s Way (aka Memory Holds the Door) and his biography of Montrose. Scholar, statesman, and bestselling novelist is a difficult combination to beat.

The genius of the Hannay novels lies largely in the character of Hannay himself. Richard Hannay is a likable man of above average intelligence, some strength, and some ambition, but he is not a superman. He succeeds by hard work, risk, loyalty, and no small amount of luck. He has his flaws. He can be stubborn, obtuse, and impetuous (in Greenmantle his overreaction to a German officers sexual advance very nearly blows his cover and sends him on the run endangering himself, his friends, and his mission). He is also capable, generous, and unusually strong and fit. In short, he’s the perfect man for an adventure. And like all Buchan’s heroes he is motivated by duty, and willing to work to near exhaustion to get the job done.

He is also one of fictions most physical characters. In Buchan’s novels no one ever rests, stands still, or lollygags around. There is almost constant movement, tension, and physicality. Reading his novels is the literary equivalent of an aerobic workout. It isn’t uncommon to finish them literally breathless. Buchan heroes work hard and succeed big. Hannay gets a knighthood, Clanroyden is always off in some backwater of the Empire playing at international politics, Edward Leithen (the most biographical of Buchan’s characters) gets a knighthood and becomes England’s Solicitor General (more of less Attorney General), and even Glasgow grocer Dickson McCunn becomes wealthy and moves with the movers and shakers of the world. Buchan’s Calvinist upbringing valued hard work and its rewards, and his own poor health led him to overcompensate in those areas.

In The Three Hostages Buchan does for the civilian thriller what his previous novels did for wartime intrigue. He creates his greatest and most complex villain in Dominc Medina (Buchan was by all accounts a genuinely nice man, and villains aren’t usually his strong suit, but Medina is an exception).

Medina is charming, charismatic, mysterious, and chilling. His near hypnotic control over people is so great that even Hannay only escapes because he is the unimaginative type and less susceptible to that sort of thing, but he plays a desperate game getting close to Medina and playing at being under his influence.

As Medina’s ambitions rise Hannay, his wife Mary, and Sandy work to out maneuver the powerful man, and it is Mary who rises to the occasion first to put the fear of God into Medina who has hypnotised a young boy and hidden him in plain sight hypnotised to believe he is a little girl:

“You have destroyed a soul,” she said, “and you refuse to repair the wrong. I am going to destroy your body, and nothing will ever repair it.”

Then I saw her meaning, and both Sandy and I cried out. Neither of us had led the kind of life which makes a man squeamish, but this was too much for us. But our protests died half-born, after one glance at Mary’s face. She was my own wedded wife, but in that moment I could no more have opposed her than could the poor bemused child. Her spirit seemed to transcend us all and radiate an inexorable command. She stood easily and gracefully, a figure of motherhood and pity rather than of awe. But all the same I did not recognise her; it was a stranger that stood there, a stern goddess that wielded the lightnings. Beyond doubt she meant every word she said, and her quiet voice seemed to deliver judgment as aloof and impersonal as Fate. I could see creeping over Medina’s sullenness the shadow of terror.

“You are a desperate man,” she was saying. “But I am far more desperate. There is nothing on earth that can stand between me and the saving of this child. You know that, don’t you? A body for a soul–a soul for a body–which shall it be?”

The light was reflected from the steel fire-irons, and Medina saw it and shivered.

“You may live a long time, but you will have to live in seclusion. No woman will ever cast eyes on you except to shudder. People will point at you and say ‘There goes the man who was maimed by a woman–because of the soul of a child.’

It’s the kind of scene Buchan does with great power and conviction, and certainly Mary’s finest moment in the book. In the end Hannay saves the victims, Medina’s cronies are given rough justice, but Medina escapes, only to come after Hannay in the wild for revenge — always a mistake in Buchan, for his heroes have an almost uncanny relation with rough country. After a desperate struggle Medina falls, and Hannay tries to save him:

He had found some sort of foothold, and for a moment there was a relaxation of the strain. The rope swayed to my right towards the chimney. I began to see a glimmer of hope.

“Cheer up,” I cried. “Once in the chimney you’re safe. Sing out when you reach it.”

The answer out of the darkness was a sob. I think giddiness must have overtaken him, or that atrophy of muscle which is the peril of rock-climbing. Suddenly the rope scorched my fingers and a shock came on my middle which dragged me to the very edge of the abyss.

I still believe that I could have saved him if I had had the use of both my hands, for I could have guided the rope away from that fatal knife-edge. I knew it was hopeless, but I put every ounce of strength and will into the effort to swing it with its burden into the chimney. He gave me no help, for I think–I hope –that he was unconscious. Next second the strands had parted, and I fell back with a sound in my ears which I pray God I may never hear again — the sound of a body rebounding dully from crag to crag, and then a long soft rumbling of screes like a snowslip.

I managed to crawl the few yards to the anchorage of the gendarme before my senses departed. There in the morning Mary and Angus found me.

And there it ends, with Hannay alive and returned to the bosom of his family and Medina dead and broken on the rocks below. The Three Hostages is a remarkably prescient novel too. Buchan not only warns of the dangers of the post war world, but the strange lassitude that seems to fill England and Europe and the kind of man, men like Medina — and Adolph Hitler — who will use it to build their power bases and threaten all of civilization:

‘In ordinary times he will not be heard, because, as I say, his world is not our world. But let there come a time of great suffering or discontent, when the mind of the ordinary man is in desperation, and the rational fanatic will come by his own. When he appeals to the sane and the sane respond, revolutions begin.’

That’s a pretty fair interpretation of the madness Europe would soon descend into ending in another, and more vicious war.

There are one or two minor racial matters to deal with in the book and some of Buchan’s earlier books, but unlike fellow thriller writers of the period Buchan came early to be embarrassed by these remarks and even removed them from later editions of some of his books. He was an early voice decrying Fascism and the plight of the Jews in Germany, and an early supporter of the Jewish movement in Palestine.

Throughout his career he was a voice of reason, though certainly prey to the errors and the prejudice of his time and world. The most embarrassing passages in the book deal with a discussion of Gandhi. But in Buchan’s case I think forgiveness comes more easily than with some others. First he was a splendid writer, second a genuinely good person, and most important a man who gave his life that the Western World might untite in a time of danger against the forces of darkness and barbarity.

Hannay appears briefly to introduce The Courts of Morning (where Sandy Clanroyden, Archie Roylance and his wife Janet, and John S. Blenkiron are involved in a South American revolution), and the narrator of one of the short stories in the collection, The Rungates Club, and finally in one last adventure with Sandy and Hannay’s teenaged son, Peter John, Man From the Norlands (aka Island of Sheep).

There are three film versions of The 39 Steps, including the Hitchcock classic, a remake with Kenneth More as Hannay, and a third version with Robert Powell. There was also a short lived BBC series called Hannay. The Three Hostages (1977) was a made-for-television film shown here on PBS with Barry Foster as Hannay and John Castle as Medina, Clive Donner directed.

Also screenwriter Stephen DeRosa has uncovered evidence Alfred Hitchcock considered filming The Three Hostages, and that it may have influenced his first film of The Man Who Knew Too Much.

There was a silent film of the Dickson McCunn book, Huntingtower and later a BBC mini series, and Buchan’s Witch Wood, a novel of about devil worship in seventeenth century Scotland, was also adapted for television.

The Three Hostages shows Hannay at his most mature and capable, and Buchan at his best. Away from all the trappings of his earlier shockers he nevertheless creates a suspenseful and intelligent tale that at once demonstrates the mental state of the world in the post war era and at the same time warns of the dangers that world is prone to.

Good thrillers aren’t rare, but genuinely prophetic ones are. The Three Hostages succeeds as both a thriller and a prophetic look at a new breed that would use the unrest and disquiet of the post war era to play havoc with European society — the very ‘rational fanatic’ Buchan warned of.

Nor is the hint of occult powers and dark matters far off the mark from the Occultism practiced by the Nazi’s — a sinister Indian hypnotist named Kharama features in the novel, but turns out to be less dark than he is painted — literally. It is also some how prophetic that the evil in the novel is defeated by decent men who refuse to be swayed by attractive and easy solutions. Like Buchan himself they choose hard work, duty, and simple decency.

And all that might not amount to much if The Three Hostages wasn’t also a first class thriller with genuine puzzle elements. The obscure Latin quote that leads Hannay to Medina and the rescue is handled with intelligence and skill, and in these days of Da Vinci Code ripoffs and pseudo-scholarship, it is nice to know that Buchan managed to create a quote so realistic that for years Latin scholars sought its source before finding it was original to Buchan.

You can find more on Buchan at the John Buchan Society website.

Note: The quote was: ‘Sit vini abstemius qui hermeneuma tentat aut hominum petit dominatum.’ Translated in the Oxford University Press World Classics edition by Professor Miller as: ‘whoever seeks to interpret the world or seeks to exercise power over men should be an abstemious drinker of wine’. Or: ‘He who tries to interpret or seeks to dominate men should not drink wine.’ I don’t think even Christie ever managed to plant a clue that fooled classical scholars.