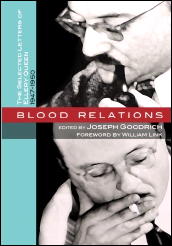

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

When the present loses its savor, turn to the past. I recently reread a suspense novel first published in my childhood and first encountered something like 45 years ago. I remembered very little about it except that it hadn’t impressed me much back in the Sixties. It still doesn’t, but some aspects of it merit space here.

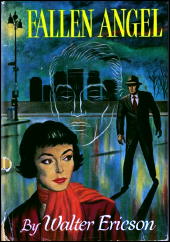

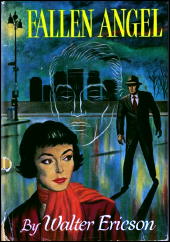

The byline on the first edition of Fallen Angel (Little Brown, 1952) was Walter Ericson but the author was Howard Fast (1914-2003), who is best known for mainstream novels like Spartacus and for his Communist affiliation, which sent him to prison for three months during the McCarthy-HUAC era.

According to his memoir Being Red (1990), he decided to present his first crime novel under a pseudonym because in those years of Red Menace paranoia he was afraid publishers would soon be boycotting all books by openly Marxist writers like himself.

Then some patriotic munchkin at Little Brown tipped off the FBI, and J. Edgar Hoover himself called the CEO with the message that it was okay for the book to appear under Fast’s own name but that the house would be in trouble if it came out under a pseudonym. With the book already printed and bound, the dust jacket copy was hastily revised to announce that Ericson was Fast’s newly minted byline for mystery fiction.

Critical reaction ran the gamut. Anthony Boucher in the New York Times Book Review called the book “something short of sensational… [It] has a few adroitly contrived pursuit scenes in the Hitchcock manner, but a limp, tired plot, an equally tired set of stock characters, rather heavy prose and unlikely dialogue, and a general air of never quite making sense.â€

At the other end of the spectrum, the reviewer for the Boston Herald found the novel “surprisingly absorbing and masterfully created…,†evoking a “mood that is often savage with a skein of madness.â€

The Michigan City News-Dispatch described it as “full of chills and thrills, ripe with suspense and psychological undertones.†The Cincinnati Enquirer praised the “good creepy atmosphere and excellent fast writing.†(Pun intended?)

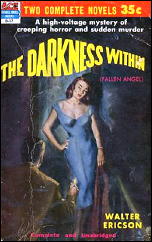

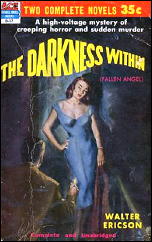

These and other raves were reprinted in two pages of front matter when Fallen Angel appeared in paperback, retitled The Darkness Within. This early Ace Double (#D-17, 1953) was bound together with the softcover original Shakedown by Roney Scott, who turned out to be PI novelist William Campbell Gault.

Apparently no one tipped off J. Edgar this time: the byline on the Ace edition is Walter Ericson and there’s no hint anywhere that Fast was the author.

The springboard situation here is as purely noir as in any Woolrich novel. The narrator, David Stillman, is in a Lower Manhattan skyscraper late one March afternoon when the lights suddenly go out and the building loses all power.

Descending 22 stories by the fire stairs, he encounters a lovely woman who seems to know him well but whom he doesn’t know at all. He follows her into the bowels of the building but loses her. Out on the night street he finds that a renowned public figure who kept an office in the building has fallen 22 stories to his death.

Arriving home, he discovers a gunman in his apartment who presents him with a forged passport and orders him to leave for Europe at once. All this in the first four chapters!

Stillman soon becomes convinced that he’s been suffering from amnesia for the last three years, but in Chapter Five he visits an obese and grotesque psychiatrist who calls him a liar to his face:

“So you have amnesia yet you don’t know you have it. No, Mr. Stillman, there is no such thing, only in Hollywood on the films, but in life there is no such thing. Even amnesia — it is for two, three weeks, Mr. Stillman, not for three years.â€

Whether Fast is right or not I have no idea but this passage seems to be a clear reference to Woolrich’s The Black Curtain (1941; filmed the following year as Street of Chance), which begins with the restoration of the protagonist’s identity after an amnesia lasting precisely three years.

Fast devised a storyline squarely in the Woolrich vein, and left as much unexplained at the end as Woolrich ever did, but he simply didn’t have Woolrich’s awesome skill at making us live inside the skins of the hunted and the doomed, feeling their terror as they run headlong through the night and the city.

David Stillman’s first-person narration constantly seeks to evoke a sort of existential dread — perhaps the threat of World War III and the fear of nuclear holocaust — but the style is absurdly pretentious and didactic:

“Here [in Central Park] a man was being hunted as men had been hunted in the forgotten past — and by creatures out of the past, or out of the future perhaps, creatures without sympathy or love or compassion or pity.â€

That last quartet of nouns illustrates another problem with the style: endless repetition. I’ll limit myself to two exchanges of dialogue, both from the climactic scene:

“I had to find something out,†I said. “Something I didn’t know. Something I couldn’t remember.â€

“But now you remember?â€

“Now I remember,†I said.

And then:

“I haven’t got it,†I said.

“You’re a damned liar, David.â€

“I haven’t got it,†I repeated evenly. “Do you hear me, I haven’t got it, Vincent.â€

Multiply by hundreds and you’ll get it. The picture that is.

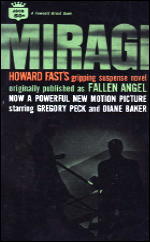

Speaking of pictures, The Black Curtain was filmed the year after its publication but Fast’s novel didn’t make it to the big screen until after his post-imprisonment break with the Party.

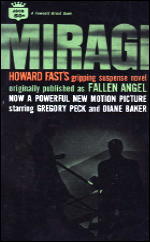

Mirage (1965) was directed by Edward Dmytryk, another member of the creative Left (although he avoided prison and salvaged his career by “naming names†before HUAC), and starred Gregory Peck and Diane Baker, with the performance of a lifetime by Walter Matthau as the hapless PI Peck consults.

Dispensing with first-person narration, Dmytryk and screenwriter Peter Stone eliminate the novel’s stylistic faults, but the film never generates the powerful mood of the finest noirs of the Sixties, like Cape Fear and Point Blank.

As a tie-in with the movie there came a paperback edition of the novel (Crest #d808, 1965), for obvious reasons retitled Mirage but now credited to Fast.

The back cover is graced by an amusing six-word condensation of Tony Boucher’s Times review: “Pursuit scenes in the Hitchcock manner.â€

Just a few years later Mirage was loosely remade as Jigsaw (1968), directed by James Goldstone in a hallucinogenic visual style, with Bradford Dillman and Harry Guardino replacing Peck and Matthau.

When Fast was in his early eighties I had a brief exchange of letters with him about his World War II court-martial novel The Winston Affair (1959) and the very different film version Man in the Middle (1964), which starred Robert Mitchum as a sort of Philip Marlowe in khaki. (Google my name and the movie title and you’ll find my University of San Francisco Law Review essay on that subject.)

If only I had reread Fallen Angel back then and asked him about that book too!