Fri 18 Jul 2008

A Review by Mary Reed: S. S. VAN DINE – The Benson Murder Case (Take 2).

Posted by Steve under Authors , Characters , Reviews1 Comment

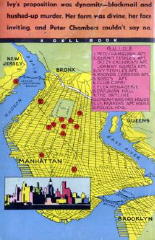

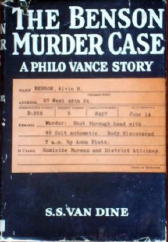

S. S. VAN DINE – The Benson Murder Case. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926. Hardcover reprints include: A. L. Burt, no date (shown); Gregg Press, 1980. Paperback reprints include: Pocket #333, 1945 (shown); Fawcett Gold Medal T2006, no date (ca.1968); Scribner’s, 1983 (shown).

Narrator ‘Van’ Van Dine originally met Philo Vance at college and is now not only a close friend but also his full-time legal and financial advisor. He is thus on the spot to record cases in which Vance becomes involved.

Vance is rich and cultured, possessing many beautiful and rare examples of art and artefacts from various eras and continents. He easily out-Wimseys Wimsey, what with addressing people as ‘Old dear’ and constantly talkin’ ragin’ nonsense, often dropping French or German into conversations with an occasional bit of Latin for variety, not to mention quoting luminaries such as Milton, Longfellow, Cervantes, and Rousseau as well as Spinoza and Descartes. But it’s all a front, of course.

John Markham, DA for NY County, arrives at Vance’s flat while Van and Vance are discussing business and announces wealthy broker Alvin Benson has been murdered. Alvin’s brother Major Anthony Benson has asked Markham to take charge, and Markham had promised Vance he would take him along on his next important investigation. It seems the authorities were casual about protocol as well as crime scenes, because not only do both Vance and Van tag along but they are also present at several interrogations.

At one point Vance produces a list of suspects based upon reasoning from available information and physical evidence. The only snag is they are innocent. It is a demonstration of his conviction that “The truth can be learned only by an analysis of the psychological factors of a crime and an application of them to the individual”.

Who then is the culprit? The actress Muriel St Clair, in whom the dead man had taken more than a passing interest? Her fiance Captain Philip Leacock, he of the hasty temper and jealous disposition? Major Benson, given the brothers did not get along? What about Mrs Anna Platz, Alvin’s housekeeper, who seems to be hiding something, or the precious and impecunious Leander Pfyfe, a close friend of the deceased?

My verdict: Some will find Vance’s insistence on keeping the identity of the murderer secret irritating but given he had it sussed out within an hour or two of visiting the crime scene, one can see why.

To be fair, he all but takes Markham’s hand and leads him to the culprit. There are clues aplenty, and to my delight the author provided those much-loved and now sadly missed tidbits — a room plan, a character list, and footnotes from Van.

Although readers may find Vance’s lit’r’y meanderin’s a bit tedious, his explanation of his psychological reasonings are interesting and convincing, although I am still not certain if the author was sending it up or using it as a genuine plot device. All in all, however, a good read with plenty of red herrings to confuse the issue.

Etext:

http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks02/0200341h.html

[EDITORIAL COMMENT.] Mary sent me this review back in September of ’07, along with a backlog of others. (Sorry, Mary!) I’ll get more of them online here soon, but after posting Bill Loeser’s recent comments about the same book, I thought I ought to pull this one out of the queue and give it some priority, the idea being that two independent views of a book are better than one, and certainly far better than none. (Where else has The Benson Murder Case been reviewed in the last 10 or 20 years?)

That’s a rhetorical question. You needn’t answer it.