Fri 4 Apr 2008

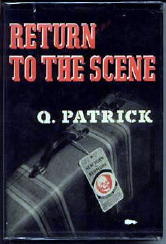

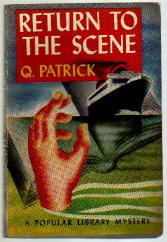

Archived Review: Q. PATRICK – Return to the Scene.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Magazines , Reviews[4] Comments

Q. PATRICK – Return to the Scene.

Books, Inc.; hardcover reprint, March 1944. First edition: Simon & Schuster/Inner Sanctum, 1941. Paperback reprint: Popular Library #47, ca. 1945. Serialized previously in The American Weekly as “The Green Diary.”

I don’t know how long this website will stay up, but it presently contains loads and loads of the beautiful (if not exquisite) artwork that filled the covers of The American Weekly in its heyday. While the examples are all from 1918-1943, the magazine, a Sunday newspaper supplement for the Hearst chain, continued on through the years until the title changed to Pictorial Living in 1963, then folded for good in 1966. (Information obtained from Phil Stephensen-Payne’s magnificent Magazine Data File website.)

Which is not relevant to anything more than the fact that this novel by Q. Patrick first appeared there, nothing more, but you really ought to see those covers.

(I couldn’t resist. The one shown here is from 1941, the artist Joe Little, and as you see, one of the authors who had a story in that issue was Max Brand.)

As for Q. Patrick, there is no way I am going to try to completely untangle the web of real names that lie behind that pen name and that of Patrick Quentin (and Jonathan Stagge). Suffice it to say that Return to the Scene was the result of the primary two collaborators who used that pseudonym, Richard Wilson Webb and Hugh Callingham Wheeler. On other Q. Patrick titles, Webb had as partners, at various times, Martha Mott Kelley and Mary Louise Aswell — pairwise, mind you, not in triple tandem.

It is interesting to note that Mary Aswell’s two efforts with Webb took place in 1933 (S. S. Murder) and 1935 (The Grindle Nightmare), and her single solo effort did not appear until 1957 (Far to Go).

As for Patrick Quentin (and Jonathan Stagge), we’ll leave any discussion of who they were (and when) for another time, but as well known as practitioners of the Golden Age variety of detection, none of the various aliases, nor their books, are very well known today.

Nor of course is Quentin/Patrick alone in this category. The rise and fall in popularity of various authors over the years is a subject that is likely to come up often in these pages in the days to come. Why, for example, are Agatha Christie’s books so timeless, and Borders has nothing on the shelves by Ellery Queen or Erle Stanley Gardner, and only a handful of titles by Rex Stout? John D. MacDonald’s books may be in print, but only from Amazon. I’ve not seen them on any actual bookstore shelves, new, in quite a while.

Not that answers are likely to be very forthcoming and/or definitive, but the question at least will be something that will turn up in one of these review/commentaries every once in a while.

Case in point. Return to the Scene, by Q. Patrick. Is it a book very likely to be published today? Answer, possibly, but not by a major publisher. Maybe by a small independent publisher like the Rue Morgue Press, which specializes in reprinting classic (and obscure) mysteries from the Golden Age, of which Return to the Scene is obviously one — and if you have gotten this far into this (which eventually will turn into a review), you really should be supporting them, and if you aren’t, then shame on you — or one of those publishers that specializes in large print editions for libraries, under the obvious assumption that only older people who can’t see so well any more will have any interest in reading them any more.

It starts out like a romance novel — this is now the review — with Kay Winyard rushing to back to Bermuda to stop her niece from marrying the man she once thought she was in love with, before she discovered what kind of man he was and walked out on him. And in her purse is her weapon, a diary. A very revealing diary written by the woman who did marry him, in spite of Kay’s warning, and who subsequently killed herself because of him.

It very quickly becomes instead a murder mystery, however, and there is no surprise to learn who the victim is. The rich, the powerful Ivor Drake, who is soon also very dead. And with a huge house of possible suspects, all of whom (it is also quickly discovered) had reasons to wish him that way.

The police investigate, and for one reason or another, no one tells them the truth. Alibis are created out of happenstance and convenience. Every one has their own package of facts that they do not wish to be known, and webs of intrigue and would-be (and only reluctantly admitted) love affairs make learning the complete truth next to impossible even for Kay, who is an insider, much less Major Clifford, the ultimate outsider.

Here’s a long quote from pages 116-117. It begins with Terry talking to his sister, Elaine. Elaine is the girl whose marriage Kay came back to Bermuda to stop:

“Killed Ivor!” Elaine have a sharp little laugh that was like a sob. “You and Kay! Why do you keep on saying that I killed him? Why would I have wanted to kill him? You don’t even know if he was murdered. It’s just Major Clifford, something crazy he said. It isn’t true. It’s all a terrible nightmare and we’re going to come out of it.”

“It isn’t a nightmare, Elaine. It’s real. And there’s no hope for us unless we tell each other the truth.”

“But what can I tell you when — when I don’t know anything?”

Brother and sister were staring at each other with a cold, desperate intensity.

Alliances are built, along with the stories the players tell the police, then collapse, and bit by bit the truth gets put together like a gigantic jigsaw puzzle. Delicious! There are clues aplenty, and the alibis so spontaneously constructed eventually cannot stand up under the pressure, and they begin to fall apart. Not one of the alibis, as it happens, is any good.

The ending is disappointing, a little, but this (it seems to me) is what almost always happens. The explanation is so mundane, so unworthy, so why-didn’t-I-think-of that, but only, you realize, in comparison to the mystery itself.

Another problem is that when the victim is so dastardly as this one is, one hates to see anyone found guilty of the crime, although of course someone must be, and in the end, all of the pieces fit together. (At least without a careful re-reading, all the way through, they do.)

Not a classic, but in the Golden Age, even the non-classics came close.

PostScript: A preliminary checklist of titles in the Books, Inc., line of Midnite Mysteries, of which this book is one, can be found by following the link provided.