After the

discussion on this blog about the two versions of Steve Fisher’s

I Wake Up Screaming, Frank Loose asked the following question in the comments section:

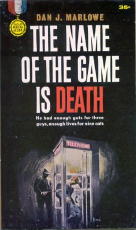

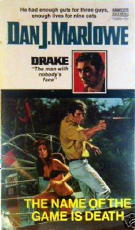

“If I understand correctly, Black Lizard did a similar thing with Dan Marlowe’s The Name of the Game is Death. I believe their edition is of a revised, tamed down version of the book, and that the original first edition was a bit more violent. Perhaps you can enlighten me on this?”

I asked around but didn’t get anything specific about this, so I asked on the rara-avis Yahoo group. Mark Sullivan posted the following response, which he’s allowed me to reprint here. NOTE the spoiler alert partway through.

I have both Gold Medal versions of The Name of the Game is Death, but I don’t have the Black Lizard version to compare them to. However, some time ago, I posted this comparison, so perhaps [from this] you can tell us which BL used:

I recently found a copy of the 1962 The Name of the Game is Death. I haven’t read it yet, but I have compared it to the copy I already had [which was] “Copyright 1962, 1972 … Printed in the United States of America, January 1962/January1973”

The story is exactly the same. The earlier one has one extra chapter, but that is only because the later edition combines Chapters VIII and IX. However, the book has been extensively rewritten, from first page to last. The language of the earlier one is a bit more clipped, more “just the facts” simple sentences, but longer paragraphs.

Here are two examples. The first two paragraphs from 1962:

“From the back seat of the Olds I could see the kid’s cotton gloves flash white on the steering wheel as he swung off Van Buren onto Central Avenue. On the right up ahead the strong late September Phoenix sunshine blazed off the bank’s white stone front till it hurt the eyes. The damn building looked as big as the purple buttes on the rim of the desert.

“Beside me Bunny chewed gum rhythmically, his hands relaxed in his lap. Up front, in three-quarter profile the kid’s face was like chalk, but he teamed the car perfectly into a tight-fitting space right in front of the bank.”

From 1973:

“From the back seat of the Olds I could see the kid’s cotton gloves flash white on the steering wheel as he swung the car from Van Buren onto Central Avenue. The strong, late-September, Phoenix sunshine blazed off the bank’s white stone front till it hurt the eyes. The damn building looked as big as the purple buttes on the rim of the desert.

“Beside me Bunny chewed gum rhythmically, his hands relaxed in his lap. Up front the kid’s face was like chalk, but he teamed the car perfectly into a tight-fitting space right in front of the bank.”

So it’s close, but subtly different.

And the last chapter, from 1962: [SPOILER ALERT]

“I was in black darkness for six months. I may have gone a little crazy, too. I gave them a hard time. I went the whole route: baths, wet packs, elbow cuffs, straitjackets, isolation. I stopped fighting them a little while ago. They don’t pay much attention to me now.

“Even before I could see again, I knew what I looked like. I could feel the reaction, when a new patient was admitted, or a new attendant came on duty. Hazel came to see me four or five times. I refused permission for her to be allowed in.

“They don’t know that I can see again, that I’m not crazy. They think I’m a robot. A vegetable.

“I’ll show them.

“I have a hermetically sealed quart jar buried in the ground up in Hillsboro, New Hampshire, and another in Grosmont, Colorado, up above the timber line. There’s nothing but money in both. I don’t need it. All I need is a gun. Some one of these days I’ll find the right attendant, and I’ll start talking to him. It will take a while to convince him, but I’ve got plenty of time.

“If I can get back to the sack buried beside Bunny’s cabin, plastic surgery will take care of most of what I look like. With a gun, I’ll get back to it.

“That’s all I need — a gun.

“I’m not staying here.

“I’ll be leaving one of these days, and the day I do they’ll never forget it.”

And from 1973:

“I was blind for six months.

“I may have gone a little crazy, too. I went the whole route: baths, wetpacks, elbow cuffs, straitjackets, isolation. I stopped fighting them a while ago. They don’t pay much attention to me now.

“I knew what I looked like even before I could see again. I could tell from the reaction when a new patient was admitted or a new attendant came on duty. Hazel came to see me five or six times. I refused to consent for her admission.

“They don’t know that I can see again. That I’m not crazy. They think I’m a robot. A vegetable.

“I’ll show them.

“There’s a hermetically sealed quart jar buried in Hillsboro, New Hampshire, and another in Grosmont, Colorado. There’s nothing but money in both. I don’t need money. All I need is a gun. One of these days I’ll find the right attendant, and I’ll start talking to him. It will take time to convince him, but I’ve got plenty of time.

“Plastic surgery will take care of most of what I look like if I can get back to the sack buried beside Bunny’s cabin. With a gun, I’ll get back to it.

“That’s all I need — a gun.

“I’m not staying here.

“I’ll be leaving before too long, and the day I do they’ll never forget it.”

Again, same content, slightly different presentation. Nothing had to be changed to make it a series. As a matter of fact, the prologue in my copy of One Endless Hour (March 1969/January 1973) begins with yet another close, but not quite the same, version of the last chapters of The Name of the Game. I don’t have the Vintage edition, so I can’t tell you which version they used, one of these or yet another one.

The individual changes that Mark mentions are interesting but essentially only stylistic. The consensus has always been that drastic changes had to have been made, in order to transform the hero into a series character. The changes demonstrated by Mark certainly don’t fall into that category.

In the meantime, Frank was also asking the question to a few other people. Here’s the reply he received from Chuck Kelly, who is very definitely an expert on Dan Marlowe’s books. He agrees with Mark in terms of the stylistic changes, all relatively minor, but then goes on and provides what appears now to be a definitive answer:

Thanks for your question on the two versions of The Name of the Game Is Death.

There are indeed two versions, both published as Fawcett Gold Medals. The original one was published in 1962, and the revised version was published in 1973. It is sometimes said that the 1973 version is a “toned-down” version, but, with a couple of exceptions, that really isn’t true. In fact, it’s basically just a rewrite with some different phrasing, paragraph structure, etc.

The significant differences in the story in the two versions, and they are rather subtle, have to do with a couple of passages in which the main character discusses his sexuality with his new girlfriend, Hazel Andrews. In the 1962 version, the character appears to be a bit more uncertain about his heterosexuality than he does in the 1973 version.

Also, in the 1962 version, there’s the implication that killing turns him on, which is removed from the 1973 version. The change probably was made to make the character fit more closely the “secret agent” Drake character readers knew by then, one who was sexually potent and a tough guy, but not a wanton killer.

The Black Lizard edition actually is a re-issue of the 1962 version, so you’ve read the story as Marlowe originally wrote it.

Phyllis A. Whitney’s books have been great favorites of mine for as long as I remember. I discovered her juvenile mysteries about the same time that I discovered her adult suspense novels, and I read both groups of books with great pleasure. Growing up on a farm in Mississippi, I did all my world-traveling in those days through books. Miss Whitney took me to far-flung, exotic places that I could never hope to go on my own, and after I read one of her books I felt I had been to those locales, if only for a brief while.

Phyllis A. Whitney’s books have been great favorites of mine for as long as I remember. I discovered her juvenile mysteries about the same time that I discovered her adult suspense novels, and I read both groups of books with great pleasure. Growing up on a farm in Mississippi, I did all my world-traveling in those days through books. Miss Whitney took me to far-flung, exotic places that I could never hope to go on my own, and after I read one of her books I felt I had been to those locales, if only for a brief while.