REVIEWED BY CONNOR SALTER:

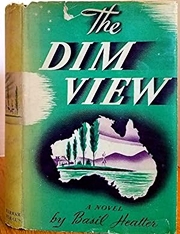

WILLIAM LINDSAY GRESHAM – Limbo Tower. Rinehart & Co., hardcover, 1949. Paperback reprints listed below.

Crime fiction fans know Gresham for his 1946 classic noir novel Nightmare Alley and nonfiction classics on carnival/magician culture (Houdini: The Man Who Walked Through Walls and Monster Midway: An Uninhibited Look at the Glittering World of the Carny). In 2010, Bret Wood released Grindshow: The Selected Writings of William Lindsay Gresham (see Walker Martin’s Mystery*File review here for more details).

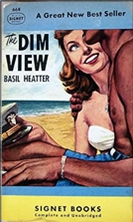

Few people today know about Gresham’s second novel, Limbo Tower, although it had some commercial success. My copy (William Heinemann, 1950) is the second hardcover edition, and Signet/New American Library published at least three paperback editions (Signet 839 in 1951, Signet D2046 in 1962, then a reprint of D2046 in 1973).

It’s a curious mix of crime thriller and melodrama. The limbo tower in question is an urban tuberculosis clinic—TB is a harsh disease, so the quarantined patients are in limbo between life and death. For the main character, Jewish atheist Communist poet Benjamin Rosenbaum, the rest-and-nothing-else routine is torture. He’s got words to write and systems to smash.

Catholic nurse Anne Gallagher struggles to care for him well because she can’t admit she’s in love with an atheist. Other patients—most notably Muslim cab driver Abdullah, con man Jasper Stone, and fundamentalist preacher Joe Kincaid—orbit around Rosenbaum, amusing or irritating each other. Meanwhile, Dr. Rathbone struggles with being a skilled surgeon in a job where his options to cure patients are limited. His colleague, Dr. Crane, strives to hide an affair with a woman whose boss is on the hospital board.

Many interesting things could be said about how the novel connects with Gresham’s real life. Gresham spent about six months in tuberculosis wards (leaving against doctors’ advice) in 1939-1940. He dedicates the book to Alexander F. Bergman, a poet who died of tuberculosis and was “a genius, a revolutionary, and an expert at handling small boats. God rest him, he’s dead now.”

Readers familiar with Gresham’s wife, Joy Davidman (she later married C.S. Lewis, a romance depicted in the movie Shadowlands) will know she edited They Look Like Men, a collection of Bergman’s poetry. All interesting things that biographers and researchers are still unpacking today.

The more interesting topic for crime fans is how much Limbo Tower feels like it wants, and doesn’t want, to be a crime novel. Wood (and Alan Prendergast in a Writer’s Chronicle piece) observe that the tuberculosis setting and ensemble cast make Limbo Tower resemble Thomas Mann’s novel The Magic Mountain. I found it felt more like a mix between Jim Thompson’s The Alcoholics and Elmore Leonard’s Touch.

Like The Alcoholics, it’s an ensemble clinic story with noir elements, yet its subject matter announces that it’s meant to be “serious literature.” In Gresham’s case, the crime comes via hints that preacher Kincaid has sinful secrets and Dr. Crane’s affair with a femme fatale who talks like the brunette in Detour.

In Thompson’s case, the crime comes via his usual tropes (women with odd sexual interests, heroes with unmentionable dark pasts), just in a clinic instead of his usual small Texas town. Yet Thompson makes his goal fairly clear: he highlights the fact the clinic is a “California gothic” style building, his ensemble cast resembles a gothic novel’s quirky mansion residents, and the essential dilemma is over accepting much-needed money from a crooked source (“how will we maintain the mansion?”).

This is noir returning to its gothic roots. Gresham’s much longer, rambling story doesn’t have such clarity: there’s a lot of talk about religion, allusions to people’s criminal pasts, and some vague hints of supernatural phenomena, but it never coheres into a clear vision. In both cases, attempting to write a self-consciously serious novel feels like overreaching. Thompson and Gresham seemed at their best when they took a pulp novel setup (con jobs, bank heists, etc.), then quietly made it more radical.

Like Leonard in Touch, Gresham offers a curious mix of piety and grit. Leonard isn’t strictly a noir writer, although his trademark messy urban characters and snarky humor seem to build on noir’s legacy of fast-talking crooks—hence why Tarantino liked Leonard so much.

In Touch, a novel about hucksters exploiting a Franciscan priest whose stigmata can heal people, Leonard wants to be simultaneously snarky and reverent. The religious elements aren’t scorned, as we’d expect from someone who wrote Rum Punch. Similarly, Gresham (writing during the tail end of his 1946-1950 churchgoing Christian phase, contributing testimonies to Presbyterian Life about how much C.S. Lewis’ apologetics informed his faith journey) takes faith seriously here. Readers familiar with Nightmare Alley, where the con artist hero poses as a spiritualist minister, keep waiting for a reveal where the faithful turn out to be fools. Instead, even Rosenbaum’s angry Communist tirades against religion are treated as misguided faith. Leonard and Gresham both try to combine writing styles known for irony and cynicism with pious treatments of religion. Neither quite pulls it off.

So, Limbo Tower is a messy book. That being said, Gresham provides some memorable scenes—including a wicked twist in Dr. Crane’s love life. The descriptions of the hospital—particularly the biblical allusions to Babel/Babylon as its furnace burns contaminated sheets—are also fun. The characters could use a stronger plot to orbit around, but they are all intriguing. As readers saw in Nightmare Alley, Gresham had a knack for making a community of characters feel like the universe in microcosm.

Maybe now that Guillermo del Toro has made Nightmare Alley into a movie and some lesser-known Gresham works have crept back into print (Dunce Books re-released Monster Midway in 2021), we’ll see new interest in Limbo Tower. I’m unsure how well a reissue would sell, but I can see a smart adaptor playing with the structure to make a compelling audiobook or graphic novel.

____

About the Reviewer: G. Connor Salter is a writer and editor living in Colorado. He has contributed over 1,400 articles to various publications, including Mythlore, The Tolkienist, and Fellowship & Fairydust. His interview with mystery author Clayton Rawson’s son was published here earlier in Mystery*File.