Sat 6 Dec 2025

by Dan Stumpf:

Centuries hence, fans and academics may still be sorting through the cultural remnants of the Twentieth Century looking for something worthwhile. When they speak of Mysteries, I hope they will be kind.

I hope that whoever they are, the literary historians of the future will pass lightly over those exaggerated grotesques that passed for Eccentric Detectives from the pens of authors who wrote as if they’d never in their lives met a Real Person. I hope they will skip over the showy blowhards who tried to pass off Violence as Realism and Platitudes as Philosophy.

And perhaps they won’t even mention those puzzle-writers who mistook Contrivance for Cleverness.

There now; Have I covered all the bases without actually offending anyone? What’s that? A word or two about the pretensions of Wordy Critics? Well, I think that may be going too far, so I’ll skip to the punch line.

I hope, in short, that our Future Forefathers (?) will ignore all that overrated dreck and spend most of their time talking about Fredric Brown.

No, not everything that Brown wrote was dipped in gold, and a lot of his stuff is awfully routine, but when Brown was at his peak, no one could touch him tor speed and agility. In the Science Fiction genre, Philip K. Dick sometimes came close to emulating Brown’s counter-logic (so neatly displayed in his short story collections Honeymoon in Hell and Nightmares and Geezenstacks), but in the realm of the Clever Mystery — light, fast-paced and ingenious — no one (not even that ponderous puzzler Agatha Christie) ever came close.

A lot of trees have died in the last several years, sacrificed to weighty articles demonstrating that Brown’s Content is a lot deeper than his Style would indicate, and I will admit that there’s quite a bit beneath the surface of books like Here Comes a Candle, The Wench Is Dead and Martians, Go Home.

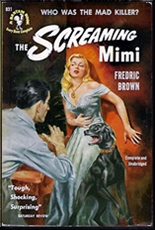

I particularly like the fearful symmetry of The Screaming Mimi, which opens and closes with the hero talking to God and demonstrates along the way that God is not a particularly nice person. You could even string Brown’s short short stories together into a chapbook of commentary on the futility of Human Endeavor and I think be reminded irresistibly of the disciplined poetry of Omar Khayyam’s effort in that direction.

But what impresses me most favorably about Fredric Brown is his sheer love of writing for its own sake, and his ability to communicate this love to the reader. Following the twists and turns of a Fredric Brown story recalls the thrill one gets from seeing Astaire dancing or Olivier doing Shakespeare or Gershwin playing Gershwin: The sheer felicity of a gifted artist doing what he loves best has an appeal all its own.

This felicity comes across very appealingly indeed in Homicide Sanitarium (Dennis McMillan, 1984), with an introduction by Bill Pronzini) a very welcome collection of previously unreprinted Brown stories that was followed by another half-dozen or so volumes in the same vein.

Reading these tales, one gets some idea of what the Mystery Story can be at its best as well as a fascinating glimpse into the workings of Brown’s uniquely inventive mind.

“Red-Hot and Hunted” for instance starts off as a moody chase story, then veers subtly into whodunit, as the Brown starts dropping subtle hints that All is not What It Seems, then wraps up with a fast, surprising but logical solution — it also shows Brown’s gift for creating plausible red herrings, characters who seem to have lives of their own outside the confines of the pages but who fit quite comfortably into the restrictions of even a short story plot.

My other favorite in this collection, the title story, offers the engaging Brown-logic of an escaped Homicidal Maniac who hides out in a Sanitarium. There’s a lot more to this story than merely the cute logic of what would have been a facile punch-line in the hands of a lesser writer.

For Fredric Brown, the idea is a starting point, a place to begin his story and characters from. He is thus able to do a great deal with a very simple premise Not for Brown the lugubrious machinations of a Mystery where Everybody Dun It or the character-flouting of a puzzle that makes a mockery of Motivation.

He keeps one hand on his premise but the other one very firmly on plausible characterization and the result is writing in which even the most outrageous of crimes (and another story in this collection, “The Spherical Ghoul” features the most ludicrous puzzle I have come across in years) still does not insult the reader’s intelligence.

Fredric Brown’s talent was probably a little too diffuse to earn him a very high place with most critics. Like Michael Curtiz, he seems to have crafted gems in almost every genre but never settled down to that predictable consistency that makes the works of Woolrich or Hitchcock so much easier (and therefore critically popular) to analyze.

I hope, though, that in some golden future time, when some of the more grotesque “giants” of the Mystery have gone to a well-deserved obscurity that fans or academics or both will still be reading Brown.

NOTE: For more, much more from the pen (?) of Dan Stumpf, check out his own blog, filled with great fun and merriment at https://danielboydauthor.com/blog