Trick AND Treat:

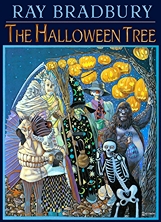

The Halloween Tree on Page and Screen

by Matthew R. Bradley.

When I interviewed Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) in 1994, he explained the genesis of his novel The Halloween Tree (1972), whose youthful protagonists were based directly on his own childhood experiences and friends, “In many ways, or experiences I had later in Mexico. It’s an amalgam of memories and my interest in Halloween. I painted a picture [in 1960] called The Halloween Tree, a large tempera painting, it’s about three feet by four feet…I was having lunch with Chuck Jones, the animator, one day…It was the day after Halloween and It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown [10/27/66] had been on, which I hated, and all my children ran over and kicked the TV set because they promised you the Great Pumpkin and [then] he never appeared.

“Well, you can’t do that to kids, you know. You cannot promise them something that exciting, you’ve got to have [him] appear. Maybe it’s an illusion, maybe it’s a trick, whatever, the children think they see [him] and we the audience know that they don’t see him. But nevertheless, one way or the other [he’s] got to show up.

“So I was complaining about this to Chuck [who made the classic How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (12/18/66) for MGM], and he said, ‘Well, hell, why don’t we do our own film on Halloween and do it right?’ [So] I brought him my painting and lugged it over to the animation studio and he said, ‘My God, that’s it, that’s the genetic tree, that’s the family tree of Halloween.

“‘Let’s go back in time to the caves and the Greek and Roman myths, and come on up through Europe with the Druids and into Ireland and Scotland and England and America and Mexico. You write the screenplay,’ which I promptly did in the fall of [that year], I believe.

“And in about two months I had the thing ready to shoot, at which point MGM tore down all of its animation studios and fired everyone. We were all out on the street suddenly. I peddled the screenplay around and optioned it to various animation studios off and on for many years, and it took a good part of twenty years to finally get someone else interested,†during which he converted it into a novel illustrated by Joseph Mugnaini.

In “a small town by a small river and a small lake in a small northern part of a Midwest state,†Tom Skelton and seven other boys dressed for All Hallows’ Eve are perplexed by the absence of Joe Pipkin, “the greatest boy who ever lived.†Emerging from his home pale, unmasked, and holding his right side, he pledges to catch up with them at “the place of the Haunts†in the inevitable ravine, whose tall, black-clad resident, Carapace Clavicle Moundshroud, slams the door with a “No treats. Only — trick!â€

Behind the house, they see the titular tree hung with 1,000 jack-o’-lanterns, and after rising from a pile of leaves in the guise of a skull, he offers to reveal “all the deep dark wild history of Halloween…â€

For this, they must travel to the Undiscovered Country (i.e., the Past), and when they say they must await Pip, he appears, feeling unwell, but in the ravine, his pumpkin light goes out, and he vanishes. Moundshroud says Death has “borrowed†Pipkin, “perhaps to hold him for ransom,†and taken him to the Undiscovered Country, so the lads can “solve two-mysteries-in-one.â€

He has them build a kite out of circus posters covering an abandoned barn, a pterodactyl with the boys (including Ralph Bengstrum and Wally Babb) as its tail, followed by a scythe-carrying Moundshroud, his cape serving as wings; they fly over the town and into Egypt, 2000 B.C., where food is left on doorsteps for homecoming ghosts.

Deducing that the youthful mummy in the funeral procession they are watching is Pip, his friends are eager to save him, but Moundshroud cautions patience, proceeding to explain how fire got the cavemen through the night, wondering if the sun would rise the next day. Atop a pyramid, they see similar offerings being made in ancient Greece and Rome; from there, the wind blows them off to the British Isles to see “England’s own druid God of the Dead,†Samhain, who turns the dead to beasts for their sins. A dog amidst this maddened menagerie, Pip eludes them again before they watch animal sacrifices being made by the druid priests, cut down by Roman soldiers who themselves are cut down by Christians…

In the Dark Ages, the boys are carried off by brooms, prompting a lesson in how “anyone too smart, who didn’t watch out,†was accused as a witch; they “liked to believe they had power, but they had none…â€

In Paris, Pip is chained as the clapper of a bronze bell on a huge scaffolding, and as they ascend to free him, Notre Dame builds itself beneath their feet, its giant shadow banishing the witches. Reaching the top and finding Pip gone, they whistle for gargoyles to ornament the cathedral, realizing that one figure is Pip, who says he is not dead yet, with parts of him in the places they’ve been and “a hospital a long way off home,†but a lightning bolt knocks him off before Pip reveals how they can help him.

Moundshroud says they must reassemble the Autumn Kite and fly to Mexico, the night’s “last grand travel†and a place of powerful association for Bradbury, who was frightened by the mummies in the catacombs of Guanajuato and set several stories there.

On El Dia de los Muertos (The Day of the Dead Ones), the boys see the graveyard filled with people singing and placing flowers, cookies, sugar skulls, candles, and miniature funerals on the graves of their loved ones. Opening a trapdoor in an abandoned cemetery, Moundshroud says they must bring Pip up from the catacombs below, where they find him at the end of a long hall, both he and they too terrified to run the gauntlet with 50 mummies on a side.

Moundshroud proposes a bargain: breaking a sugar skull bearing Pipkin’s name in eight pieces, he says they can ransom him if each gives a year from the end of his life, so they agree and eat the bits. Freed, Pip races right past them and disappears, so Moundshroud transports them back to Illinois, noting that “It’s all one…Always the same but different, eh? every age, every time. Day was always over. Night was always coming….Summer and winter, boys. Seedtime and harvest. Life and death. That’s what Halloween is, all rolled up in one.†The boys learn that Pip’s appendix was taken out just in time and, after decorating his porch with lit pumpkins to await his return, drift back to their own homes.

Continued Bradbury, “finally David Kirschner…of Hanna-Barbera, came into my life. We talked about it for a year or so, and then finally two years ago he came back and said, ‘Hey, we got the money, Ted Turner’s one of our new bosses, and we want to buy The Halloween Tree. Will you freshen up your screenplay?’ I said, ‘I sure will.’

“So I spent a couple of months [on it]…and that was it…Nothing was changed after that. We added a little more narration…They said, ‘Look, you’re ignoring your own best qualities here. Let’s add more of your individual voice, and let’s have you read it, hunh?’ And by God they were right. I went into the studio and read the narration, and it’s a nice addition.â€

The film halves the trick-or-treaters to Jenny (voiced by Annie Barker), replacing Henry-Hank Smith in the Witch costume, Tom (Edan Gross; Skeleton), Ralph (Alex Greenwald; Mummy), and Wally (Andrew Keegan; Gargoyle).

Backed with evocative music by John Debney, an Oscar nominee for The Passion of the Christ (2004) who’d also worked with producer — and in this case director — Mario Piluso on Jonny’s Golden Quest (1993), the narration is almost verbatim from the book. After seeing Pip (Kevin Michaels) taken off in an ambulance, they find a note urging them to “Go ahead without me,†but seek to visit him instead; a shortcut through the ravine takes them to Moundshroud (Leonard Nimoy).

Pip’s ghostly form takes a pumpkin bearing his likeness from the titular tree, vanishing in a tornado; this becomes a concrete cinematic MacGuffin rather than his peripatetic person or spirit, continually eluding Moundshroud, who seeks his soul.

After the kite takes them to ancient Egypt, a more kid-friendly druid episode — sans Samhain, sacrifices, or Roman soldiers to “Destroy the pagans! â€â€” is set in Stonehenge, segueing via the Broom Festival to Notre Dame, which Moundshroud says, echoing Quasimodo, offers “Sanctuary!†The gargoyles’ connection with the monster mask worn by oft-aghast Wally (a drinking game based on each time he gasps, “Oh, my gosh!†would imperil the liver) is now established.

Evoking Bradbury’s Playboy story (September 1963) and Alfred Hitchcock Hour episode (10/26/64) “The Life Work of Juan Diaz,†the final stop finds a more assertive Tom braving the mummies to reach Pip, taking the blame for wishing that something would happen to make him the group’s leader. But at the moment of forgiveness, Moundshroud grabs the pumpkin: “Children, it’s business. With his illness, his rent came due, and there was no payment. He’s mine now,†leading Tom to suggest the bargain instead. Pip flies off with his pumpkin and they are all whisked home, where it is found adorning his porch rail, Pip having narrowly survived the surgery, while Moundshroud delivers his summation about the universality of Halloween, and flies away with the remaining pumpkins from the tree.

“[I]t’s a nice film, and I…won an Emmy for it [it was also nominated for Outstanding Animated Children’s Program]. I had a wonderful relationship with the studio, and no problems, no friction. The film is…available…so people can buy it, and it’s been on two years running…It’s hard to find the damn thing. They’ll have it on in the middle of the afternoon or late at night, and I hope maybe next year they’ll have it at a decent hour.”

But I’ll leave the last word to his literary characters: “They were stopped by a final shout from Moundshroud: ‘Boys! Well, which was it? Tonight, with me — trick or treat?’ The boys took a vast breath, held it, burst it out: ‘Gosh, Mr. Moundshroud — both!’â€

— Copyright © 2023 by Matthew R. Bradley.

Excerpted from the forthcoming (God willing) The Group: Sixty Years of California Sorcery on Screen.

Edition cited:

The Halloween Tree: Bantam (1974)

Online source:

https://archive.org/details/the-halloween-tree_202106