A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

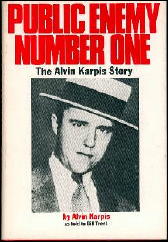

JAMES ELLROY – Blood’s a Rover. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, September 2009.

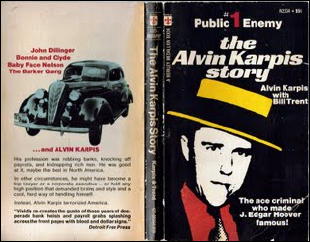

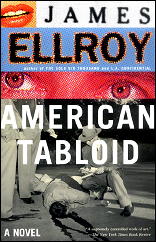

James Ellroy has long been the mad bad devil dog of crime fiction, and beginning with American Tabloid then The Cold Six Thousand, the first two books of the “Underworld USA” trilogy, he made a political move toward a sort of crackpot history of all the paranoid secret conspiracy theories of the twentieth century from the days of Bugsey Siegel in Vegas to the Kennedy election and assassination on.

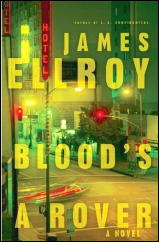

In his latest novel, Blood’s a Rover (the title is from a poem by A.E. Houseman) he has settled on perhaps the most tumultuous period in American history since the Civil War, the period from the assassination of Martin Luther King to the death of J. Edgar Hoover on the eve of Watergate, 1968 to 1972.

This isn’t to suggest Ellroy has forgotten his roots in the mystery and crime genre. The book opens with a splendidly choreographed armored car robbery in a black neighborhood in Los Angeles. It is a perfectly done scene that deserves to be filmed.

Blood’s a Rover turns on three characters and their relation to a fourth, a beautiful and legendary radical American woman, Joan Rosen Klein, aka Red Joan. The three men are Dwight Holly, J. Edgar Hoover’s personal gunman, who knows all the secrets of his secret-ridden boss and some of his own, and who may be damned by his growing humanity, thanks to his growing love for one of his informants; Wayne Tedrow, who murdered his own father, who had been part of Hoover’s operation Black Rabbit to disgrace and finally kill Martin Luther King, and who now finds as he moves to building a casino empire in the Dominican Republic that his politics are growing more radical; and Don “Crutch” Crutchfield, a young LA private eye, once Joan’s lover, and on the cutting edge of the right wing reactionaries and the left wing crazies who populate the story.

These three will be thrown into a dizzying world of violence and conspiracy tying together a brutal and bloody armored car robbery; Hoover’s plans for Operation Baaad Brother aimed at creating then cracking down on black radicals; the 1968 Presidential election, and the Chicago riots at the Democratic Convention; Sal Mineo, the Oscar-nominated actor fallen to the level of gay street hustler and informer; two psychotic LA cops, one white and one black; and Howard Hughes’ Mormon aide, a closeted homosexual — among others.

Wayne blundered into the hit plot in post-hit free fall. He linked Jack Ruby to Moore and that right wing merc Pete B. He saw Ruby clip Lee Harvey Oswald on live TV.

He knew. He did not know his father knew. It all went blooey that Sunday.

JFK was dead. Oswald was dead. He tracked down Wendell Durfee and told him to run. Maynard Moore interceded. Wayne killed Moore and let Durfee go. Pete B. interceded and let Wayne live.

Pete considered his own act of mercy prudent and Wayne’s rash. Pete warned Wayne that Wendell Durfee might show up again.

This goes on for two pages, explaining what occurred before in American Tabloid and The Cold Six Thousand, a crackpot history of American conspiracy that has ended with Hoover engineering the assassination of Martin Luther King, an event that will eventually be his downfall through Dwight Holly, Wayne, and Crutch. I’d quote more, but it isn’t easy to find a good sustained quote that doesn’t end in an obscenity or two

As Nixon nears the White House, the plots spin together in a melange of conspiracy and insanity that only ends when Crutch destroys Hoover’s secret files in an act of vandalism that triggers the FBI director’s fatal stroke.

It’s difficult to describe the book. It is written in a style that is part jazz riff and part docu-noir, and spins from one act of stunning violence to another. The plot spins in and out of control from racial politics in the LA police to Hoover’s paranoia, to the growing radicalism of the protagonists as they rebel against the world they live and operate in, much of it inspired by Red Joan who eludes Hoover and the police while planting her seeds of discontent.

Each of the three main protagonists is saved or destroyed by his own growing soul and conscience, and the book carries the story from the first two books to its logical end with the death of Hoover.

Whether or not Ellroy believes this insane plot or not is impossible to tell. The book at times seems to have been bred out of Richard Condon by way of William Burroughs and The Turner Diaries. It all makes a sort of sense if you don’t stop too long to think about it, and certainly it is a brilliant work, though at times the confluence of plots, conspiracy, violence, and secret history threatens to teeter over into something closer to the Marx Brothers than the dark secret history of our recent past Ellroy intended. His ambition has almost, if not quite, exceeded his grasp and ours.

Blood’s A Rover is the weakest of the three books in the trilogy, perhaps naturally since it is the repository for tying up all the loose ends. At times it feels as if you should have American Tabloid and The Cold Six Thousand open beside you as you read in order to keep up. Even then I don’t know if that would be possible.

But Ellroy has developed a style and voice that are unique. No one else writes like him, and no one else finds that strange mix of humor, horror, paranoia, humanity, and violence that mark his works. It is the work of a master, about the price we pay to “live history,” but it is a masterwork that dares to dance dangerously close to the edge, and by staying true to his vision, its creator risks losing some readers to its purity of vision.

There are times you may not know whether to laugh or cry, and times I’m not sure Ellroy knows whether he wants you to do one or perhaps both.

This completes the “Underworld USA” trilogy, and ties it up, though I can’t say neatly. It is likely to stand a while as a unique achievement, but it is not without flaws, not without questions unanswered, but the trip is worth taking, even if untangling the conspiratorial plot may require a bottle of aspirin, and more than one reading.

Blood’s A Rover is the work of a great writer stretching himself, but it is not a perfect work. Its flaws should not keep you away from the book, but anyone reading it should be warned. Ellroy’s world is unforgettable, but at times incomprehensible as well.

Luckily his prose carries you past the rough patches, but when you turn the final page you may not be sure how you feel about the trip. At this point I suspect the final judgment of the critics will be to find this a flawed masterpiece by one of our most interesting writers, but I can’t say I would be too surprised if their judgement was simply, “huh?” It’s that kind of book.