REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

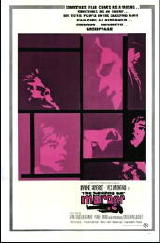

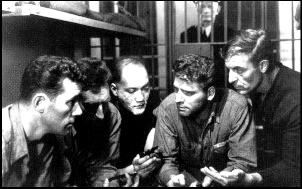

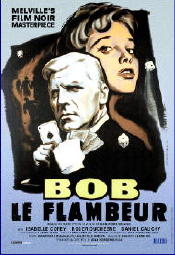

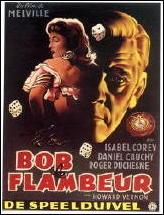

BOB LE FLAMBEUR. Mondial, France, 1956; William Mishkin, US, 1959, as Bob the Gambler. Isabelle Corey, Daniel Cauchy, Roger Duchesne, André Garet, Gérard Buhr, Guy Decomble. Director: Jean-Pierre Melville.

One of the advantages of being something of a round peg in a department of square holes is that I am occasionally allowed to teach something that “nobody else” has any interest in doing, like the course on French Film that I have just finished teaching.

Most of the films are by directors like Renoir, Clair, Virgo, Carne, and Ophuls, but I always manage to slip in a genre film by a director not many people would consider essential. In past years this meant films by Clouzot (Le Cor beau and Jenny Lamour).

This year it was Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1955 thriller, Bob le flambeur (Bob the Gambler), a film that Melville had repudiated before his death in 1972 (“I will not allow this film ever to be screened again”) but that many critics now consider to be his finest achievement in a series of studies of criminals and the criminal milieu.

Ostensibly, Bob the Gambler is an extended character study leading to a climactic caper, the robbery, by a team of well trained specialists, of the casino at Deauville.

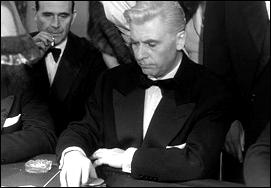

But Melville manages to undermine almost every cliche of the caper film with a rigorously analytic style that manages to distance the spectator from the characters and cut away from the caper at the climactic moment, only returning to it in the final moments to dispense almost briskly with the basic plot elements and provide a final, comically ironic look at the protagonist, Bob the gambler.

Melville, in an interview, related how, after seeing Huston’s film The Asphalt Jungle, he realized that he no longer wanted to — or could not — make a classic caper film. He decided instead to make what he called a “comedy of manners” (“comedie de moeurs”), but most American viewers will probably, like the students in my class, find this an odd film indeed.

Melville’s film preceded New Wave films like Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Godard’s Breathless by about four years, but the look of the film (shot on location in the streets and buildings of Montmartre) and the use of a jazz sound track seem to look forward to the innovative filmmaking of the late fifties and early sixties.

The credits are presented over shots of Montmartre from the “heights” of Sacre-Coeur (the church) to the “depths” of Place Pigalle, a moral distance underlined by the matter-of-fact narration of Melville.

But the spectator who expects an explicit moralistic study of the contrasts between the sacred and the profane will be disconcerted as the camera prowls restlessly along the streets, into the back rooms of cafes and restaurants, with Sacre-Coeur only present as a shape dimly glimpsed through the closed curtains of Bob’s elegant apartment.

The affection the camera shows for the landscape may be disconcerting to the viewer who is looking for a narrative thread that will engage him, but location filming is a prominent feature of New Wave films, as in The 400 Blows, whose “travelogue” beginning is reminiscent of the beginning of Bob, all the more so in that both films benefited from the same superb photographer, Henri Decae.

The final shot in Bob is of an empty car parked on a lonely stretch of beach and completes a circle initiated by the documentary shots of buildings at the beginning of the film.

The inner life of the characters is never explored in a way that is satisfying to the viewer, and it is perhaps appropriate that the frame is emptied of people at the beginning and the end.

The viewer expecting the tight plotting of Hitchcock or the claustrophobic, fatalistic character study of Huston, will be disappointed. In Melville’s work, fate is chance, but the camera lingers on geometric patterns (wall-paper, windows, a floor covering) that suggest an intercrossing of plot lines that will only be evident on repeated viewings.

The characters are elusive and the “content” of their relationships is like a crossword puzzle that may or may not be correctly filled in by the spectator.

Melville’s expressed wish that the film not be re-released has been ignored. The formal, discreet patterns of this apparently open but controlled narrative with something of the look of a photograph by Walker Evans have lost none of their capacity for frustrating the viewer accustomed to the heightened, mounting suspense of Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950) or Kubrick’s The Killing (1956).

All three of these films are about defeat and loss, but Bob manages to retrieve an ironic victory from a failure, and the sardonic humor of this victory appears to clash with the conventions it has intermittently adhered to.

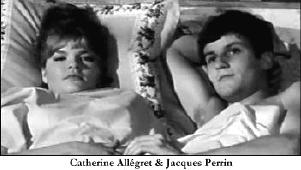

In Breathless, Goddard paid tribute to Melville by including, a reference to the character, Bob (Roger Duchesne), and by using Melville to play the role of a novelist interviewed by Patricia, the young American with whom the small-time Parisian hoodlum, Michel, has fallen in love.

She betrays Michel, echoing the thematics of betrayal in Bob, where Anne (Isabelle Corey) betrays Paulo and Bob’s careful planning, but the final irony is perhaps Melville’s attempted betrayal of his beautiful and still fascinating portrait of Bob the gambler and his Parisian milieu.

And one can only wonder to what extent Godard was again tipping his hat to Melville when one of his characters comments that he and his friends avoid Montmartre, which is dangerous for them and their “kind.”

But Godard met successfully the cinematic challenge of his gifted predecessor and his tribute is, finally, the best witness to Melville’s achievement.

– Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 2, March/April 1987.