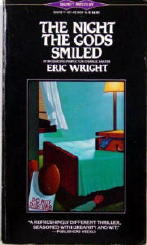

ERIC WRIGHT – The Night the Gods Smiled. Signet 13409; paperback reprint, February 1985. Hardcover edition: Charles Scribner’s Sons, September 1983. Canadian hardcover: Collins, 1983. Canadian paperbacks: Totem (two editions), 1984, 1988.

Sub-titled “Introducing Inspector Charlie Salter,” this is the first of ten mysteries solved by Eric Wright’s most well-known series character between 1983 and 1993. An eleventh (and presumably last) case for Salter, a Toronto police detective, appeared in 2002. After first appearing in hardcover, all eleven of them were later published in paperback. When the series was dropped by Signet, the rest were picked up by Canada’s own Worldwide Mysteries (also known as Harlequin).

Wright eventually added a second series character in Mel Pickett, a cop who first played a second fiddle to Salter in A Sensitive Case (1990) and then who tackled one on his own in Buried in Stone (Scribner, 1996), followed by Death of a Hired Man in 2001.

The first of two adventures of Lucy Trimble Brenner also appeared in 1996. Ms. Brenner is a librarian who inherits a Toronto private detective agency and decides to make the big career move. (I have never seen either of the two books, and I think I had better do something about it.)

In the year 2000 a fourth series character came along, a part-time community college English teacher named Joe Barley, who also works part-time as a private eye. He has two books under his belt so far, the second coming out in 2003. The latter may end up being Eric Wright’s final mystery, as he was born in 1929, making him now 77 years old, and perhaps he is no longer writing. Or he may yet surprise us. Perhaps there is yet another in the works.

Eric Wright himself was (and more than likely, in this order) professor, chair of the English department, then Dean of Arts at Ryerson Institute of Technology in Toronto, from where he is now retired. And if his first book (and also more than likely) several of his others deal with academia, one should hardly be surprised. I know I am not, and in fact after reading The Night the Gods Smiled, I highly approve.

The victim, in fact, was a professor of English at a small college in Toronto, but he was found dead in his hotel room while attending an academic conference in Montreal. The dead man’s occupation, however, gives Charlie the opportunity to interview many of his colleagues, none of whom seem to have liked the man very much, some less than others, and in the process, Charlie learns a lot about academic squabbles indeed.

There was a glass with lipstick on it in the dead man’s room. Had he picked up a streetwalker? He had also bragged of good fortune earlier in the day (hence the title). I should back up. Charlie is on the outs with the current administration of the Toronto police force. He works under the category of General Duties, and homicide is by no means his regular assignment. But the investigating officer in Montreal is French, and the roots of the crime may lie in English-speaking Toronto, hence Charlie is assigned liaison duty.

In the background is Charlie’s home life. While they are happily married, there is a class and/or cultural divide between Charlie and his wife (and children) and especially his wife’s family, who are considerably wealthier than Charlie, who gets by on a policeman’s pay, but usually no better than that. That Charlie is (platonically) attracted to the free-spirited Molly, one of the dead man’s students (and so was the professor) is part of who he is and who he is learning himself to be. She is a charmer.

Here’s a short quote taken from a conversation Charlie has with one of the dead man’s colleagues at the Faculty Club, taken from page 59:

“The thing you’ve got to understand, Inspector,” Usher said, causing Salter to hope the others would take him for an inspector of drains, “is that we all have a field. What we specialize in. My field is Lawrence. D.H. I come from Nottingham — did you realize I’m English? — and my grandfather knew Lawrence, or said he did, like most of the old codgers in Nottingham.” Usher broke off again for a sustained maniacal laugh at the lies Nottingham codgers told about Lawrence.

The paragraph is longer, but I’ve changed my mind and decided to cut it off here, omitting the rest of it. The part that I cut has Usher explaining how courses are set up and who gets to teach what course and the like, all of which is necessary for Charlie to feel himself in the dead man’s shoes, and I hope you get the idea well enough from this greatly truncated version.

The following quote shows Wright’s ability to describe something entirely ordinary and everyday, but when you look at it more closely, is not. From page 113:

The office of the Dean of Women was open, and Salter pushed the door back and walked in. A secretary looked up from her typewriter, and he introduced himself. She was the drabbest girl he has seen in some time; she looked as though she were hired for her plainness by the original sex-fearing governors of the residence. Her glasses, steel-rimmed, round, and tiny, were balanced on the end of her nose; her thick blonde hair was cut in a straight line, parallel with the bottoms of her ears; she wore a brown smock that looked like a shroud. Salter was appalled and piteous. “Is Miss Homer in?” he asked. “She’s expecting me.”

The girl stood up, took her glasses off, and smiled, transforming herself like the heroine of a musical comedy. She had beautiful teeth, and the shroud, when she was upright, clothed a perfect figure. It’s a style, thought Salter. They do it deliberately.

I have a number of other quotes jotted down to provide to you, but I will resist and behave myself. I also see that I wrote myself a note about the mystery and its solution: “somewhat frazzled at the end but OK.” It’s been a while since I’ve read the book — I’ve had to put off writing this review for several weeks, I’m sorry to say — but I skimmed through the ending again, and I was right. It’s the characters that I remember the most about this book — characters who are described as individuals and (even better) who are allowed to think and behave like human beings that we either know or see around us every day.

The book won a couple of major awards (see below) and if my opinion matters at all, at this late date, I think the author deserved them.

BIBLIOGRAPHY [With a couple of exceptions, these are the US editions only. Some books may have appeared earlier in a Canadian or British edition.]

Charlie Salter:

The Night the Gods Smiled. Scribner, hc, September 1983. (John Creasey Memorial Award, Arthur Ellis Award)

Signet 13409, pb, February 1985.

Smoke Detector. Scribner, hc, December1984.

Signet 14123, pb, February 1986.

Death in the Old Country. Scribner, hc, August 1985. (Arthur Ellis Award)

Signet 14450, pb, 1986.

Signet 14450, 2nd pr., July 1991.

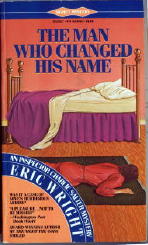

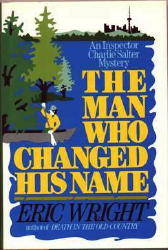

The Man Who Changed His Name. Scribner, hc, August 1986.

Signet 14930, pb, August 1987.

A Body Surrounded by Water. Scribner, hc, December 1987.

Signet 16385, pb, September 1989.

A Question of Murder. Scribner, hc, October 1988.

Worldwide 26039, pb, 1989/90?

A Sensitive Case. Scribner, hc, 1990. [Note: Mel Pickett also appears.]

Worldwide 26083, pb, Oct 1991.

Final Cut. Scribner, hc, May 1991.

Worldwide 26107, pb, Oct 1992.

A Fine Italian Hand. Scribner, hc, 1992.

Worldwide 26143, pb, 1994.

Death by Degrees. Scribner, hc, 1993.

Worldwide 26169, pb, 1995.

The Last Hand. St. Martin’s, hc, February 2002 [in which Salter, having reaching the mandatory retirement age of 60, does exactly that]

Worldwide 26569, pb, 2006.

Mel Pickett:

A Sensitive Case. Scribner, hc, 1990. [Note: A Charlie Salter case in which Pickett also appears.]

Worldwide 26083, pb, Oct 1991.

Buried in Stone. Scribner, hc, March 1996.

Scribner, trade pb, January 2001.

Death of a Hired Man. St. Martin’s, hc, March 2001.

Worldwide 26521, pb, 2005.

Lucy Trimble Brenner:

Death of a Sunday Writer. Foul Play Press, hc, 1996.

Death on the Rocks. St. Martin’s, hc, June 1999.

St. Martin’s, trade pb, June 1999.

Joe Barley:

The Kidnapping of Rosie Dawn. Perseverance Press, hc, 2000. (Barry Award)

Perseverance Press, trade pb, October 2000.

The Hemingway Caper. Castle Street Mysteries (Canada), trade pb, April 2003. No US publication.

Collection:

Killing Climate: The Collected Mystery Stories Eric Wright. Crippen & Landru, trade pb, August 2003. Collection of 16 stories, one original. A limited hc edition also appeared.

“Licensed Guide.” Criminal Shorts, ed. Eric Wright & Howard Engel, Macmillan Canada, 1992

“The Boatman.” [“Start with a Tree”]. Paper Guitar, ed. Karen Muhallen, 1995

“One of a Kind.” Secret Tales of the Arctic Trails, ed. David Skene-Melvin, Simon & Pierre, 1997

“Twins.” A Suit of Diamonds, ed. Anon., Collins, 1990

“Two in the Bush.” Christmas Stalkings, ed. Charlotte MacLeod, Mysterious Press, 1991

“The Duke.” 2nd Culprit, ed. Liza Cody & Michael Z. Lewin, Chatto & Windus, 1993

“Kaput.” Mistletoe Mysteries, ed. Charlotte MacLeod, Mysterious Press, 1989

“Caves of Ice.” EQMM, March 2002

“Hephaestus.” Cold Blood II, ed. Peter Sellers, Mosaic, 1989

“Bedbugs.” Das Magazin, April 26 1996

“Duty Free.” Cold Blood V, ed. Peter Sellers, Mosaic, 1994

“Jackpot.” [“Looking for an Honest Man”]. Cold Blood, ed. Peter Sellers, Mosaic, 1987

“The Cure.” Fingerprints, ed. Beverley Beetham-Endersby, Toronto: Irwin, 1984

“The Lady from Prague.” Cold Blood IV, ed. Peter Sellers, Mosaic, 1992

“An Irish Jig.” The Globe and Mail, December 22, 2001

“The Lady of Shalott.” [Insp. Charlie Salter]. Original.

Lodgings for the Night. Crippen & Landru, August 2003. Separate pamphlet accompanying the limited edition of A Killing Climate: The Collected Mystery Stories by Eric Wright, Crippen & Landru, 2003.

EDITOR: Criminal Shorts: Mysteries by Canadian Crime Writers, ed. Eric Wright & Howard Engel, Macmillan Canada, hc, 1992.

SOURCES:

Allen J. Hubin, Crime Fiction IV.

William J. Contento, Mystery Short Fiction: 1990-2004.