Mon 21 May 2007

Review by Mary Reed: MELVILLE DAVISSON POST – The Sleuth of St. James’s Square

Posted by Steve under Authors , Characters , Crime Fiction IV , Reviews[2] Comments

Lesser known are two other characters, Randolph Mason, a lawyer in the 1890s who advises his clients on how to commit crimes and avoid punishment; and the detective of note in the book reviewed below, Sir Henry Marquis. “In the far corners of the earth and in the most intimately known places the reader travels. In delightful suspense he follows the destinies of singers, hoboes, mock priests, beautiful creoles, sinister hunchbacks, and German officers to their inevitable climax.”

And with that brief introduction, Mary Reed will take it from here.

MELVILLE DAVISSON POST – The Sleuth of St. James’s Square

D. Appleton & Co., New York & London, hardcover, 1920.

The sleuth who lives in a large house in St. James’s Square, London, is Sir Henry Marquis, head of the Criminal Investigation Department of Scotland Yard. He also owns a country mansion and a villa on the French Riviera and internal evidence suggests he was educated at Rugby’s famous public school and Oxford University. He previously ran the English secret service in the India-Burma border area and had also been busy in unspecified places in Asia, although there is reason to suppose he is familiar with Mongolia. Sir Henry belongs to the Empire Club in Piccadilly and apparently goes to the opera now and then.

He is enthusiastic about scientific methods for solving crimes, mentioning dactyloscopic (fingerprint) bureaus and photographie mitrique in particular, but also laments lack of “intuitive impulse” in the men under his command. However, not all the cases in this collection of short stories are solved by deduction or even intuitive impulse, and indeed one or two end in triumph for those on the wrong side of the law. Oddly enough, although Sir Henry is the titular sleuth, in some stories he is not directly involved and in a couple he is referred to only in passing.

Shall we begin?

“The Thing On The Hearth” is blamed for the death of Mr Rodman, a scientist who invented a process to make precious gems. He is found dead in a locked room guarded by an Oriental servant and his death involves what appears to be a visitor from … somewhere else. Sir Henry visit Rodman’s New England mansion to investigate the matter.

In the next tale, Sir Henry has been looking over the memoirs of Captain Walker, head of the US Secret Service. In their ensuing discussion Walker tells him the tale of an inebriate hobo, who, when everyone else had failed, was instrumental in locating a number of stolen plates for war bonds, thus earning “The Reward.”

The following adventure involves a large sum of money Madame Barras is foolishly carrying on an unaccompanied two mile journey through the forest lying between the home of an old school friend and the village hotel in which madame is staying. Sir Henry is also a hotel guest and helps search for “The Lost Lady.”

The titled parents of a young man fighting at the front in France are extremely distressed. His fiancee has been staying out half the night motoring all over the landscape with Mr Meadows, and even admits to having deliberately picked him up! But when Mr Meadows obligingly gives a lift to Sir Henry, who is on his way to investigate a murder, footprints from “The Cambered Foot,” not to mention other clews, turn out to be not at all what they seem.

In the next story, an Englishman, an American, and an Italian are *not* sitting in a bar but rather are chatting about the justice systems of their respective countries at Sir Henry’s villa. The Italian count relates how it was legally possible for “The Man In The Green Hat,” proved without a shadow of doubt to have been guilty of premeditated murder, to escape the death penalty.

Sir Henry owns a diary kept by the daughter of his ancestor Mr Pendleton, a justice of the peace in colonial Virginia. The diary describes cases in which Pendleton was involved and this one concerns dissolute Lucian Morrow’s wish to buy a beautiful Hispanic girl from Mr Zindorf, whose ownership of her is dubious to say the least. However “The Wrong Sign” turns out to be right for saving the innocent.

Another Pendleton story follows. Peyton Marshall’s will favouring Englishman Anthony Gosford has gone missing, and it transpires Marshall’s son has hidden it for what appears to be good reason. But can the lad’s unsupported claims be proved, allowing him to inherit what his father promised him? “The Fortune Teller” will reveal the answer.

The next tale relates a third case involving Sir Henry’s ancestor. Pendleton meets a girl wandering about in despair. This is not surprising given her uncle, with whom she had been living, has just kicked her out of his house after informing her that her father was a rogue who robbed him and absconded. “The Hole In The Mahogany Panel” bears mute witness to the truth.

After the war is over, the traitoress Lady Muriel is in desperate financial straits as she can no longer sell British secrets. She overhears a conversation that ultimately leads to her to commit murder in order to steal an explorer’s watercolour of, and map showing the route to, a lake in the French Congo where treasure lies at “The End Of The Road.”

In “The Last Adventure” explorer Charlie Taylor has been trying to find the ancient route of gold-bearing caravans crossing Mongolia in order to salvage the precious metal from those that foundered. After he returns to America with only a few months to live, his friend Barclay undertakes to sell Taylor’s map to the location of a heap o’ gold to Nute Hardman, a man who had previously cheated Taylor.

Continuing onward, jewel dealer Douglas Hargrave meets Sir Henry at their London club. Sir Henry is puzzling over an advertisement run in papers in three European capitals, trying to deduce what “The American Horses” represent in an obviously coded message. Then Hargrave meets a lady who wants to buy a large lot of valuable gems from a Rumanian who demands payment in cash….

Lisa Lewis, American Ambassadoress, relates next a curious tale at a dinner party at Sir Henry’s house. “The Dominion Railroad Company” has experienced a number of terrible accidents and fears numerous reports alleging negligence will lead to its bankruptcy. Yet despite all possible precautions the Montreal Express derails because of “The Spread Rails.” Lisa’s friend Marion Warfield, who has revised a highly praised textbook on circumstantial evidence, solves the mystery.

At the same dinner party Sir Henry describes the case of the hardhearted lawyer who demands more money to represent a butler on trial for murdering his employer. The money cannot be found and the accused’s wife wanders the streets in despair. A wealthy opera singer takes pity on her, treats her to a meal, and listens to her story. Is she a fairy godmother in the modern equivalent of “The Pumpkin Coach,” and can she help the man on trial?

In the case following, Miss Carstair is having doubts about her marriage to diplomat Lord Eckhart despite her fiance’s gift of a stunning ruby necklace, for she is extremely troubled by gossip he is the worst ne’er do well in London. While she is pondering the matter Dr Tsan-Sgam, who has been dining with Sir Henry, arrives with news of the death of her father in the Gobi Desert, ultimately learning of its connection to “The Yellow Flower.”

Up next, a post-war story narrated next by a weekend guest at Sir Henry’s country house. Sir Henry reveals the true story of an incident on a hospital ship boarded by Prussian submarine commander Plutonberg. Wounded St Alban defies him with the fighting words “Don’t threaten, fire if you like!”, becoming an instant hero to the British. But there’s a lot more to it than that, and a situation as bitter as the rolling waves is revealed in “A Satire of the Sea.”

In the final yarn, the uncle of narrator Robin tries to put him off visiting him, but the envelope in which the letter arrives has a hastily scrawled appeal to ignore the contents and come to The House By The Loch. Will his uncle’s labours to cast a perfect Buddha ever be successful? Who is the highlander sitting knitting while talking about the Ten Commandments and taking a great deal of interest in the movements of Robin’s uncle?

My verdict: A first rate collection with several stories having a O. Henryesque twist or two and catching the reader by surprise. My favourites were “The Last Adventure,” a wonderful biter-bit yarn, and “A Satire of the Sea,” with its psychological underpinnings. An author’s note for “The Man In The Green Hat” cites a specific case and readers may like to know it was heard by the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals in 1913.

Etext: http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/

Original story appearances [taken from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin] —

* The Cambered Foot [“The Man from America”] • ss Ladies Home Journal Nov 1916

* The End of the Road • ss Hearst’s Magazine Nov 1921

* The Fortune Teller • ss Red Book Magazine Aug 1918

* The Hole in the Mahogany Panel • ss Ladies Home Journal Apr 1916

* The House by the Loch • ss Hearst’s Magazine May 1920

* The Last Adventure • ss Hearst’s Magazine Sep 1921

* The Lost Lady • ss McCall’s Jun 1920

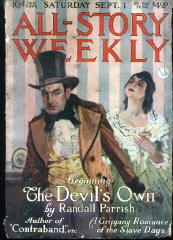

* The Man in the Green Hat • ss The Saturday Evening Post Feb 27 1915

* The Pumpkin Coach • ss Hearst’s Magazine Oct 1916

* The Reward [“Five Thousand Dollars Reward”] • ss The Saturday Evening Post Feb 15 1919

* A Satire of the Sea • ss Hearst’s Magazine Feb 1918

* The Spread Rails • ss Hearst’s Magazine Jan 1916

* The Thing on the Hearth • ss Red Book Magazine May 1919

* The Wrong Sign [“The Witness of the Earth”] • ss Hearst’s Magazine Apr 1916; with added material.

* The Yellow Flower • ss Pictorial Review Oct 1919