REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

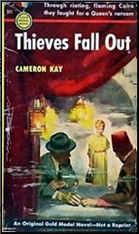

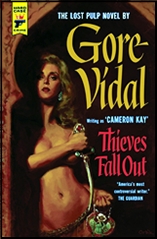

CAMERON KAY – Thieves Fall Out. Gold Medal #311, paperback original, 1953. Hardcase Crime, paperback, April 2016.

The bright Cairo noon dazzled his eyes. Shimmering waves of heat made the modern buildings across the wide street quiver as though they were fashioned of gray rubber… It must have been a rough night, he thought, moving toward a booth where a grizzled, bearded villain was selling cigarettes.

It was when he came to pay for the cigarettes that he discovered he had been robbed.

If you ever wondered what a Casablanca-style Fawcett Gold Medal original (GM 311) novel by Gore Vidal might read like, Thieves Fall Out is your chance to find out.

The hero, who we meet when he wakes up in what appears to be a whorehouse (never stated), having been drugged and robbed on his first night in Cairo is Pete Wells, ex-roughneck, combat veteran, and recently deck hand on a freighter to pay his passage to Cairo, where he feels something will come his way because things are happening in post-war Cairo.

Like him getting rolled his first night ashore.

The American Consul is no help with his plight, but does find him a half decent room in a clean hotel and it is there he meets the bald, pink Englishman Hastings (An honest open face… with a grin concealing a larcenous soul…) who takes him to meet Countess Hèléne de Rastinac (“I always feel like spy when I sit in this room…â€), a beautiful woman who has an offer for him. It seems there is a certain relic that needs to be transported out of Cairo, not entirely legally, but it’s only a minor crime, and Wells could earn enough to help him out of his dilemma and then some by taking on the simple job.

Of course, nothing could possible go wrong…

It has to be pointed out that the world of thriller fiction would be seriously diminished if the protagonists had the common sense of a poodle.

Vidal was one of the enfant terrible of the literary scene. His work was almost always brilliant and often shocking to be shocking, spinning dizzyingly from the serious literary fictions like his war novel Williwaw and his controversial The City and the Pillar; to broad social satire like Myra Breckenridge written to shock for the sake of shocking; well-written historical novels like Julian, Burr , 1876, and Lincoln, prize winning plays like The Best Man; and as Edgar Box, a trio of sophisticated mystery novels modeled loosely on Mickey Spillane’s formula as Vidal saw it, featuring Public Relations man Peter Cutler Sargeant.

In addition he twice sought public office, became a political commentator, was outspoken about his sexuality and sex in general, and famously feuded with both William F. Buckley and Norman Mailer, both of which threatened him with violence and different points. His interests were catholic and you might find him waxing eloquent about American politics one day and writing nostalgically about Edgar Rice Burroughs and Tarzan in Esquire the next.

His long public career was marked by deliberate provocations of just about any sensibility he could manage as well as fascinating insights into the famous and infamous including his childhood friendship with Amelia Earhart. He was related to both Al Gore and John Dickson Carr among numerous other figures in American history, and impressed with almost none of them.

It’s little wonder one his best books was narrated by the infamous Vice President Aaron Burr who shot Alexander Hamilton in a duel and barely escaped with his neck in one of the most infamous plots in American history.

For much of the 20th Century following WW 2 it was simply impossible to avoid Gore Vidal even if you wanted to in American politics, culture, or letters.

For Pete Wells, his foray into foreign adventure starts with a bit of smuggling in a country where smuggling relics was virtually a national sport to revolution, arms trafficking, assassination, no little sex (though no more so than any other books of its kind), Nazi war criminals (there may have been a law at this point certain kinds of thrillers must have at least one), and just about any other trope of the novel of international intrigue and adventure of its time for good and ill.

At its best, like the evocative opening, it is immediate and puts you down in the middle of the action with almost cinematic grace. At its worst, it gets a bit lost at times in the attempts to evoke place and time and the characters, at least the two main ones, remain a bit too much Central Casting for the author’s own good, as if having got them in position, his literary instinct was at odds with the needs of an adventure story.

You can almost feel Vidal the literary figure being reined in by Vidal the pseudonymous writer looking for a paycheck and trying to color in the lines.

For the most part he does it pretty well.

Like Graham Greene’s long lost novel Name of the Action, Vidal kept it out of print in his lifetime. Like the Greene novel it is nowhere near that bad, but it does read as if it may have been written quickly for money, not exactly a flaw in the eyes of collectors of Gold Medal originals, whose very charm is sometimes that exact feeling of immediacy and energy.

Nor is Vidal alone in his sojourn into the original paperback with Gold Medal. Robert Wilder, Mackinley Kantor, Eric Hatch, Cornell Woolrich, and Vivian Connell alll ventured there as well, and not all only for a quick buck.

He waited until there was neither light nor sound; then he looked out into the square. It was deserted except for four huddled shapes. He tried not to look at them as he quickly crossed the courtyard, but one brief glimpse showed him they had been beheaded.

He plunged once more into the maze of streets, all deserted now. Not even lamplight shone in the narrow windows. The wooden balconies were empty. The passage of the mob had frightened even its own kind, and the people hid behind shutters in darkened rooms.

Evocative stuff, and the best of this not-bad thriller by a major literary figure slumming, but not embarrassing himself or his readers, and much more authentic than you might expect from the source.