Sun 27 Feb 2011

An Old Time Radio Review by Michael Shonk: SAM SPADE, DETECTIVE.

Posted by Steve under Characters , Old Time Radio , Reviews[24] Comments

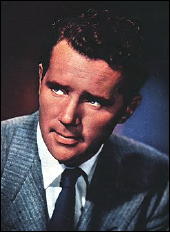

THE ADVENTURES OF SAM SPADE, DETECTIVE. ABC: July 12, 1946 through October 4, 1946. CBS: September 29, 1946 through September 18, 1949. NBC: September 25, 1949 through September 17, 1950; November 17, 1950 through April 27, 1951. Based on characters created by Dashiell Hammett. Produced and directed by William Spier. Cast: Sam Spade: Howard Duff (July 12, 1946 through September 17, 1950), Steve Dunne (November 17, 1950 through April 27, 1951), Effie Perrine: Lurene Tuttle. Announcer: Dick Joy

The Adventures of Sam Spade, Detective was popular with the radio audience and critics alike. While today it is rightfully remembered for its humor and style, the show featured great radio mysteries and moments of drama.

In “Vafio Cup Caper” (August 22, 1948), Sam chases a priceless ancient Greek cup in a mystery with non-stop twists and hilarious dialogue.

In “Edith Hamilton Caper” (April 17, 1949), Sam falls for a woman he believes killed her husband. The episode was dramatic with an effective use of music. Effie’s support for broken-hearted Sam was typical of a series that could be tearfully sad, yet end with a bitterly funny line.

Sam Spade changed when he moved to radio. Howard Duff took Bogart’s cynical loner and let him have fun. Duff’s Spade could get drunk, be short-tempered, and sleep with the femme fatale, and we would be as forgiving and admiring as his secretary Effie.

Some of radio’s top talent worked on the series.

Producer/director William Spier was famous for his popular and critically acclaimed series, Suspense. To promote Sam Spade, Spier aired an hour-long episode “The Khandi Tooth Caper,” a sequel to The Maltese Falcon, on Suspense (January 10, 1948).

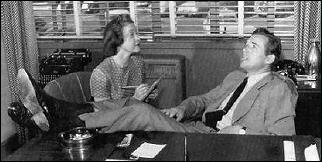

Lurene Tuttle (Effie), known as “Radio’s First Lady,” was as important to the show’s success as Howard Duff. Top radio actors would appear, often without billing. Some of the supporting cast were William Conrad, June Havoc, and Hans Conrad.

Behind the mike talent was equally impressive. Jason James (Jo Eisinger) and Bob Tallman won the Edgar award for Best Radio Drama in 1947. Other writers included Gil Doud, E. Jack Newman, and Elliott Lewis.

While Hammett had no direct involvement, the writers made good use of other Hammett characters such as in “Dick Foley Caper” (September 26, 1948). Sam tries to help an old friend from the Continental Detective agency. A highlight was when Sam told the femme fatale he knew she had a gun because it made her bulge in the wrong place.

The series did adapt some of Hammett’s short stories. “Death and Company” (August 9, 1946) was adapted from a Continental Op short story with the same title. While no recording survived, the script is reprinted in the book The “Lost” Sam Spade Scripts, edited by Martin Grams, Jr.

It would take outside forces to kill the show. Hammett was blacklisted and his name removed from the credits. When Howard Duff’s name appeared in “Red Channels”, the series sponsor, Wildroot Creme Oil Hair Tonic, canceled the series and replaced it with Charlie Wild, Private Detective (NBC: September 24, 1950 through December 17, 1950. CBS: January 7, 1951 through July 1, 1951).

According to Spade expert John Scheinfeld, the last words Duff said on radio for six years was as Spade welcoming Charlie Wild to the PI business. The only thing Charlie and Sam had in common was a secretary named Effie Perrine. No recordings of the radio show exist and who played Effie on radio’s Charlie Wild remains unknown.

Sam Spade was not off the air long. The radio audience demanded the show back and NBC quickly obeyed. The only change in the series had Steve Dunne take over the role of Sam Spade, but it was a change that cost the series its charm.

Duff had a light playful touch while Dunne’s delivery seemed forced, often sounding like a bad Jack Benny impersonator. Times were changing. Duff’s Spade was a lovable drunken womanizer, Dunne’s Spade was becoming a boy scout.

The final episode “Hail and Farewell” (April 27, 1951) was an average melodrama about saving an innocent man from execution. At the end Spade told listeners to write in and save the series. But this time the Governor did not call.

So, after over two hundred and forty episodes (around seventy are known to still exist on recordings), it really was “Goodnight Sweetheart.”

SOURCES:

â— On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio, by John Dunning

â— Radio Detective Story Hour podcast: Jim Widner (otr.com/blog)

â— Boxcars 711 podcast: Bob Camardella (boxcars711.podomatic.com)

â— Sam Spade Double Feature, Volume 1. Audio Archives: Bill Mills (audible.com)

â— OTRR.org

â— Digital Deli (digitaldeliftp.com)

â— MP3 disk with sixty seven episodes of Sam Spade, the Suspense episode “Khandi Tooth Caper”, and other extras. (otrcat.com)

There are many places where you can still find Sam Spade on the web, as well as iTunes and the Sirius XM radio series “Radio Classics.”