Thu 22 Jul 2010

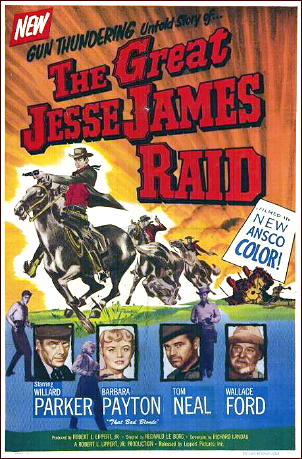

Western Movie Review: THE GREAT JESSE JAMES RAID (1953).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western movies[11] Comments

THE GREAT JESSE JAMES RAID. Lippert Pictures, 1953. Willard Parker, Barbara Payton, Tom Neal, Wallace Ford, Jim Bannon, James Anderson, Richard Cutting, Barbara Woodell. Director: Reginald Le Borg.

This movie comes as the first of six in a DVD boxed set titled “Legendary Outlaws,†so it will be easy to find, if you don’t have it and you decide to go looking. Others in the set are: Renegade Girl, Return of Jesse James, Gunfire, Dalton Gang, and I Shot Billy the Kid.

I figure that Jesse James and Billy the Kid were the two men who appeared the most often in B-western motion pictures. I don’t know which one’s the more popular, if that’s the right word, but my money’s on Billy the Kid. (I suspect that maybe you could find out on IMDB, if you wanted to, but I … What the heck. There are 80 movies with Jesse James in them, and 86 with Billy the Kid. So I win!)

Getting back to film at hand, though, Willard Parker does not make a particularly convincing Jesse James. He’s too tall, too handsome, and too blond too, for that matter.

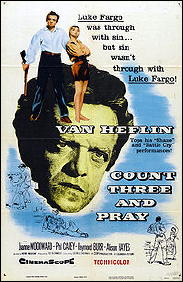

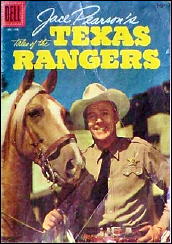

There’s no way around it. For someone who had the starring role in Tales of the Texas Rangers on TV for three years (1955-1958), he’s too stalwart, too strong, and simply too honest to play the role of a villain as if he meant it.

Strike one.

Another flaw in this film is that the ending is given away right at the beginning, when “cowardly†Bob Ford, played by Jim Bannon, comes calling one night at Mr. Howard’s house, where Jesse, his wife and son are living under assumed names. (See above.) One last job, is the deal, and Jesse falls for it. When he leaves, his wife begs him not to go, but of course he does.

Strike two.

Even though Willard Parker was decent enough as an actor, he never got the roles that would have made him a star. Not enough flair, not enough stage presence. When the real star of your western movie is Wallace Ford, playing a grizzled old-timer brought along for his skills with dynamite, sort of an Edgar Buchanan type but without the evil glint that sometimes appeared in the latter’s eye, why then, you know your budget for the film was far too low.

Well, I’ll go ahead and say it. Strike three.

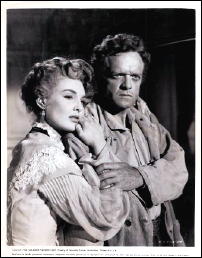

Some pluses, though. Tom Neal (of Detour fame) is a nasty piece of work, and Barbara Payton (maybe the Lindsay Lohan of her day, if not even worse) is quite a dish. (She and Tom Neal may have been living together at the time.)

But why Kate is brought along to the gold mine Jesse’s crew is working their way into, is a good question. There is no raid, per se, by the way, but things do get complicated. Not in any way that makes a lot of sense, but then again, the film is in color, and the dancing girls are nice.