Dashiell Hammett’s The Glass Key

Becomes the Coen Brothers’ The High Hat

A Review by Curt J. Evans

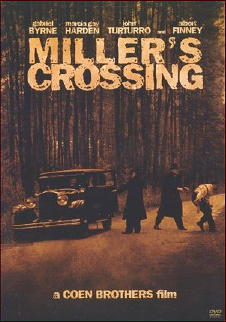

MILLER’S CROSSING. Twentieth Century Fox, 1990. Gabriel Byrne, Marcia Gay, John Turturro, Jon Polito, J. E. Freeman, Albert Finney, Mike Starr, Al Mancini, Richard Woods. Story: Joel Coen & Ethan Coen; & Dashiell Hammett (uncredited). Director: Joel Coen (& Ethan Coen, uncredited).

The best adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s highly-regarded hardboiled novel The Glass Key, the Coen Brothers’ Miller’s Crossing, does not even have Hammett’s name attached to it. But it’s Hammett all right. Hammett all over.

Characters’ names have been changed (to protect the guilty?), but many of the fundamental relationships of the novel survive intact:

â— There’s the central Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne)/Leo (Albert Finney)/Verna (Marcia Gay Harden) “love/loyalty triangle.†This equals Ned Beaumont/Paul Madvig/Janet Henry from the book.

â— There’s Leo’s rival gang leader, who attempts to usurp his place, Johnny Caspar (John Polito). He’s Shad O’Rory in the book.

â— There’s Caspar’s/O’Rory’s scarily violent homosexual sidekick, Eddie Dane (J. A. Freeman). He’s Jeff in the book.

â— And there’s Janet Henry’s “degenerate†brother, Bernie Bernbaum (John Turturro). He’s Taylor Henry in the book (though in the book he’s belly-up when the action starts).

Tom Reagan/Ned Beaumont is still a tight-lipped, ambiguous character, who keeps us guessing as to the exact nature of his thoughts and emotions. He has debt to a bookie to be concerned about but he also seems to have genuine feelings for Leo/Paul and Verna/Janet (indeed, in the film there is an ongoing physical relationship between Tom and Verna, strengthening this element from the book).

Tom’s conflicting loyalties, his feelings of honor and his attitude to violence are at the center of the film, just as they are in the book. And he sure gets beaten just about as much!

The symbolic dream of the glass key (discussed by Ned and Janet in the book) has disappeared, to be replaced by a symbolic dream of a flying hat (discussed by Tom and Verna).

Throughout this film the Coens are obsessed with hats. The film opens with a focus on a hat and closes with a focus on a hat. Tom is always losing his hat (usually while getting slapped/shoved/punched) and trying to recover it. Caspar is angered when Leo and Tom give him “the high hat†(i.e., act superior). He wants to be the one wearing the hat in Leo’s gangland kingdom.

Obviously the male hat is a symbol of power and authority. This reading is strengthened by the fact that the murder of one Leo’s henchman, Rug Daniels, results in the fallen Rug losing not only his hat but his hair (the toupee he wore).

Rug, incidentally, replaces Taylor Henry from the novel as the opening murder victim, giving his cinematic doppelganger, Bernie Bernbaum, a stage upon which to strut his nasty ways. John Turturro, who plays Bernie, performs splendidly in this capacity.

Also more memorable than his book counterpart is John Polito’s Caspar, who almost steals the show from his fellow performers — all of whom are terrific — with his colorful performance and his frequently expressed, heartfelt concern over the sad decline in gangster ethics.

J. A. Freeman’s Eddie Dane is not necessarily superior to the novel’s Jeff, but he’s unforgettable in his own right. “The Dane,†as he’s called, is smarter than Jeff and also openly homosexual (somehow “gay†simply doesn’t seem the right word for this darkly malevolent guy), being involved in his own love triangle involving Bernie and another, rather swishy character named Mink (Steve Buscemi, underused) — a plot element very important to the film’s story. In the novel and the 1942 film Jeff’s homosexuality seemed sublimated and twisted in the beatings he so enjoyed giving Ned.

While the Coens keep many of Hammett’s central concerns, they jettison class issues completely (Verna ain’t the daughter of an aristocratic senator and she certainly ain’t no lady) in favor of ethnic ones. Divisions among Irish (Leo and Tom), Italians (Caspar) and Jews (Bernie) are much emphasized in the film.

Certainly the Coens play up The Glass Key’s urban corruption angle as well, but it’s done in such a surreal, black comedy fashion it’s hard to take it too seriously as social commentary. (There’s no pretense in the film that duly elected government officials have any free hand whatsoever in determining anything that goes on in this city.)

What we are left with in Miller’s Crossing is the high hat. Which people will get to wear the hat, and how will they exercise the power that comes with it?

Anyone who enjoys Dashiell Hammett will want to see the answers the Coens come up with in this fine film.