Wed 19 Mar 2008

MIKE NEVINS on Richard Wright, Cornell Woolrich, Margery Allingham, Richard Fleischer, and INFERNAL AFFAIRS.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Columns , Crime Films , Pulp FictionNo Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

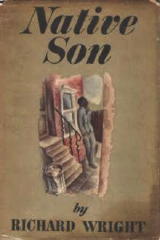

Richard Wright (1908-1960) was perhaps the best-known and most written-about black novelist of the 20th century, but as far as I know no one except myself has ever pointed out the debt he owes to Cornell Woolrich. During the late Thirties when Wright was working on his first and finest novel, Native Son (1940), he is known to have been a voracious reader of the pulp mystery magazines like Black Mask to which Woolrich contributed dozens of stories.

Native Son’s basic storyline of a young man wrongly accused of murder and running headlong through “streets dark with something more than night” was clearly inspired by Woolrich’s powerful suspense thriller “Dusk to Dawn” (Black Mask, December 1937; collected in Nightwebs, 1971).

During the last months of his life Wright was working on another crime novel, recently published in unfinished form as A Father’s Law, and it seems equally clear that here too he took his point of departure from Woolrich. In “Charlie Won’t Be Home Tonight” (Dime Detective, July 1939; collected in Eyes That Watch You, 1952) a middle-aged cop slowly becomes convinced that the criminal he’s seeking is his son. Woolrich’s cop of course is white. A Father’s Law deals with a middle-aged black cop who also becomes convinced that his son is a criminal.

If this is simply a double coincidence, it’s one that even Woolrich (who was prone to stretch coincidence to the outer limits) would have rejected. Any student of African-American literature who’s in need of an unexplored topic could do worse than to investigate the Woolrich-Wright interface in depth.

Silly mistakes in mystery fiction are not confined to nonentities like John B. Ethan, whose fond delusion that Zen Buddha was a person I discussed in my last column. Some of the biggest names have perpetrated howlers no less ridiculous.

Take, for instance, Margery Allingham. “The Definite Article” (The Strand, October 1937; collected in Mr. Campion and Others, 1950) finds Albert Campion called in by his friend Superintendent Oates when Scotland Yard is asked by the “Federal Police” of the U.S. (by which I presume she means the FBI) to arrest and deport a “society blackmailer” whose extortion drove a young woman in New York to suicide.

Excuse me? Where’s the Federal crime? Where’s the Federal jurisdiction? Any doubts that Allingham knew nothing about the American legal system should be allayed a little further in the story when Campion asks Oates why the Feds got in touch with Scotland Yard instead of, say, “the Sheriff of Nevada.” Since when do states have sheriffs?

Richard Fleischer (1916-2006) directed some of the worst big-budget movies ever to issue from Hollywood but started out helming several excellent little specimens of film noir, perhaps the best known being The Narrow Margin (1952) and Violent Saturday (1955).

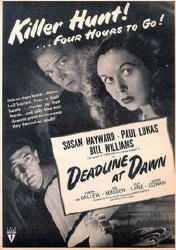

His memoir Just Tell Me When to Cry (1993) says very little about most of his noirs but includes a neat anecdote about a similar film he had nothing to do with. In 1946, as a novice at RKO, he sat in on a production meeting with tough-as-nails executive producer Sid Rogell and the well-known theatrical director Harold Clurman, who was helming his first movie. Fleischer doesn’t name the picture but, since Clurman made only one movie in his life, it has to be Deadline at Dawn, loosely based on Cornell Woolrich’s novel of the same name.

As Fleischer remembered the meeting, the first thing Rogell told Clurman was: “You don’t have forty days to shoot the picture. You’ve got thirty.” Then Rogell picked up the script, noticed that the first scene took place at night and called for rain (in film noir, what else?) and asked Clurman: “Rain? You know how much fucking rain costs?….What do you want rain for?” “For the mood,” Clurman told him. “Fuck the mood. No rain.”

Rogell was about to order Clurman to cut back on the number of people who appeared in the scene when the director interrupted: “How about dust? Lots of dust blowing everywhere. Can we afford dust?”

In the finished film the first scene takes place indoors – the confrontation between the blind pianist (Marvin Miller) and his predatory ex (Lola Lane) – and neither rain nor dust appears in the second scene, which is set outdoors but was clearly shot on a soundstage.

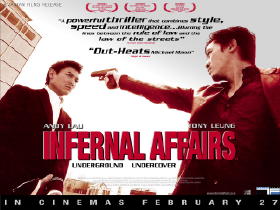

So many people have told me that I absolutely must see Infernal Affairs (2002), the Hong Kong movie which Martin Scorsese remade with Leonardo di Caprio and Matt Damon as The Departed, that I finally did it earlier this month.

The Asian film tells the same story as its U.S. counterpart – the duel between two moles, one planted in the mob years ago by the PD, the other planted in the PD by the mob – but much more tightly and cynically and without the graphic in-your-face violence that seems to have become a Scorsese trademark.

If you’ve hesitated because you’re unfamiliar with Asian action films and are afraid you won’t be able to tell the characters apart, I can assure you that this is not a problem. The wispy-mustached police mole in the mob (Tony Leung) could never be confused with the clean-shaven mob mole on the force (Andy Lau), and the only cop whose knows his mole’s identity (Anthony Wong) could no more be mistaken for the only mobster who knows his mole’s identity (Eric Tsang) than could Martin Sheen for Jack Nicholson in Scorsese’s version.

I do recommend, however, that Infernal Affairs be seen in letterbox. The panned-and-scanned version I got from Netflix eliminates far too much of each image from an intensely visual film – and one that goes far towards proving that noir has become a universal language.

How silent is the night — how clear and bright!

How silent is the night — how clear and bright! The year The Bride Wore Black first came out is commonly considered the year when film noir came into being. But the more movies I see from the years immediately preceding 1940, the more I tend to question that consensus. Turner Classic Movies recently and for the first time ran

The year The Bride Wore Black first came out is commonly considered the year when film noir came into being. But the more movies I see from the years immediately preceding 1940, the more I tend to question that consensus. Turner Classic Movies recently and for the first time ran  Devotees of films noir and their fictional sources will want to check out Kevin Johnson’s

Devotees of films noir and their fictional sources will want to check out Kevin Johnson’s  His fourth EQMM original, “Tyger! Tyger!” (October 1952), is perhaps the finest short crime story to deal centrally with poets and poetry. Malcolm Ridge, struggling to express his feelings about the Atomic Age, becomes prime suspect in the murder of the owner of a Russian restaurant in Greenwich Village and uses his skills as a poet not only to clear himself and identify the real killer but also to use the experience in conjuring up the exact words his poem-in-progress needed.

His fourth EQMM original, “Tyger! Tyger!” (October 1952), is perhaps the finest short crime story to deal centrally with poets and poetry. Malcolm Ridge, struggling to express his feelings about the Atomic Age, becomes prime suspect in the murder of the owner of a Russian restaurant in Greenwich Village and uses his skills as a poet not only to clear himself and identify the real killer but also to use the experience in conjuring up the exact words his poem-in-progress needed.