Thu 18 Mar 2010

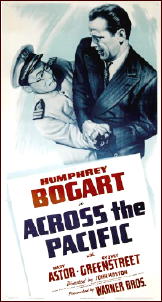

A Movie Review by David L. Vineyard: ACROSS THE PACIFIC (1942).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Suspense & espionage films[10] Comments

ACROSS THE PACIFIC. Warner Brothers, 1942. Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Sidney Greenstreet, Victor Sen Yung, Keye Luke, Charles Halton, Richard Loo, Monte Blue. Screenplay by Richard Macauley, based on a Saturday Evening Post serial “Aloha Means Goodbye” by Robert Carson. Directed by John Huston .

Mary Astor: Well if anyone heard you complaining about it they would put you in a psychopathic ward.

It was inevitable that any follow up to The Maltese Falcon was going to be anti-climactic, which is a shame, because this lighthearted flag-waver has a myriad of charms all its own including the sexual byplay between Bogart and Mary Astor, and Sidney Greenstreet’s treacherous Dr. Lorenz.

And it probably didn’t help that midway through production the Second World War broke out with the very much for real attack on Pearl Harbor, and the plot about a fictional Japanese attack at the same location was suddenly too serious for this lighthearted treatment.

The production took a hiatus while the script was quickly rewritten, and somehow in the transition the title remained unchanged, even though now the ship in question never even reaches the Pacific. (It might also explain some less competent model work than usually seen from the studio effects department.)

Bogart is Rick Leland, a US Army officer cashiered for irregularities with company funds. He heads for Canada hoping to enlist, but they want no part of him, so he determines to sell his services to the Chinese and sets sail on a Japanese ship sailing for Panama and then Yokohama.

On board the ship are Dr. Lorenz (who teaches economics in Manila), his servant, and Alberta Marlowe (Mary Astor)

who claims to be a simple girl from Medicine Hat out to see the world despite a wardrobe to die for and the sophistication of a woman of the world.

And as you quickly learn, nothing is exactly what it seems. Lorenz managed to get Leland on the ship because he knows of his military background, and Leland is in reality a secret agent, his disgrace a cover designed to lure Lorenz and the Japanese into approaching him.

After a stop over in New York where Victor Sen Yung comes on board as a jive-talking Japanese American sailing East to take over family business interest, Leland and Astor stop a Filipino from assassinating Lorenz.

Mary Astor: I think I got pushed in the face by someone. My – My lipstick’s smeared.

Humphrey Bogart: Aww, you look cute.

Mary Astor: And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll go to my cabin… and faint.

the good doctor makes it clear he wants information from Leland about Panama’s defenses and is willing to pay for it while Leland romances Miss Marlowe

Humphrey Bogart: You stick around with me and you’ll get plenty of practice.

and ingratiates himself with Lorenz.

Once in Panama, things move fast. Astor disappears, and Greenstreet outwits Leland and gets the plans for the Canal’s air defenses. Leland meets a Chinese at a Japanese theater in Panama where a well staged shootout ensues, and then heads for a plantation that has been mentioned as a place of interest.

There he finds Astor, the daughter of the westerner (Monte Blue) forced to front for the Japanese, and discovers a hidden airfield built in the jungle. It’s December 6th, 1941, and using the information gotten from Leland, the Japanese are going to bomb the Canal to coincide with the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Of course they are no match for our hero, who dispatches Victor Sen Yung with a right cross and grabs Richard Loo’s .50 caliber machine gun to shoot down the bomber and take care of the rest.

Back at the plantation Sidney Greenstreet contemplates hari-kiri, but lacks the nerve and Leland arrests him.

And as they step outside a formation of American planes flies over:

No one is arguing that this is the same category as The Maltese Falcon, but it is a remarkably assured and entertaining spy film with dialogue that sparkles and real sexual tension between Bogart and Astor.

This often gets lost among the bigger (and better) films of Bogart and Huston, but deserves to be seen and enjoyed. It’s fast, flip, sexy, and well acted by all concerned.

Maybe we should just be grateful that there are so many great films that this terrific good film gets lost in the shuffle. This tongue-in-cheek thriller is still fresh and smart, and more modern than most similar films of the era.

Note: Huston left to join the war effort and the final scene was shot by Vincent Sherman. And for some reason the two maps showing the Canal in the film are wrong. The one at the end of the film upside down with the Pacific on Panama’s East Coast! I suppose it’s possible the intent was to keep the enemy from using the maps, but you have to imagine the Japanese knew where the Canal was. You wouldn’t think it would be that easy to disguise.