Sun 16 Aug 2020

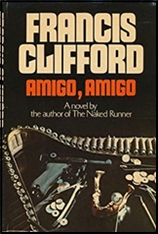

A 1001 Midnights Review: FRANCIS CLIFFORD – Amigo, Amigo.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[3] Comments

by Bill Pronzini

FRANCIS CLIFFORD – Amigo, Amigo. Coward Mccann, US, hardcover, 1973. Pocket, US, paperback, 1975. Academy Chicago, US, paperback. First published in the UK: Hodder & Stoughton, 1973.

Few writers of suspense/adventure novels, British or American, can match Francis Clifford for sheer elemental tension, depth of characterization, and prose of rare smoothness and creative imagery. Clifford’s novels are edge-of-the-chair thrillers with global settings – Mexico. Guatemala, England, Ireland, the Eastern Bloc states — and up-to-the-minute plots involving the IRA, espionage activities, the cold war, and random terrorism.

But more than that, they are psychological studies of considerable power that adhere to a common theme, as stated by Clifford himself in an interview: “Only during strain – a moral, a physical, or a psychological strain – do you get to know your own character … it is only under such circumstances that the right character of a man emerges.”

The personal trial by fire of Anthony Lorrimer, a cynical, self-involved, “cold fish” British journalist. begins in Mexico City. About to return to England, he is approached by a man with something to sell – a manuscript purportedly written by Peter Riemeck, a former high-ranking Nazi who was once Heydrich’ s deputy. This manuscript, according to the salesman, tells not only what happened to those Nazis who fled to South America after the collapse of the Third Reich, but which of them are still alive, their cover identities, and their present whereabouts.

Lorrimer isn’t about to buy a pig in a poke; he demands proof – and gets it: one name, SS-Oberführer Lutz Kröhl, a former Auschwitz administrator now calling himself Karl Stemmle and living the purgatorial existence of a curandero – a dentist and healer –in an isolated village on the rim of a Guatemalan volcano.

Lorrimcr goes to Guatemala to meet Kröhl/Stemmle face to-face: the final proof, After an exhaustive trip by plane, bus, and on- foot he arrives in the. village of Navalosa, where he finds Sternmle gone for the day and the German’s young, bored, and promiscuous native woman, Mercedes, a willing sexual partner. All along Lorrirner has been wondering: What kind of man is Sternmle? Why would he choose to lead the kind of life he does? When he finally meets the ex-Nazi, he realizes there are no easy answers. It isn’t until he and Stemmle and Mercedes find themselves captives of mountain bandits that Lorrimer begins asking those same questions of himself and learns who the real Anthony Lorrimer is.

Clifford makes the reader feel the heat, the thin air, the frightening desolation of the Guatemalan wilderness; he also makes the reader care about his characters, even the most incidental of them. The Chicago Tribune said that Amigo, Amigo “takes all superlatives,” and that it “will keep you mesmerized.” Indeed it will. If you enjoy literate thrillers that really are thrillers, don’t miss this one.

And don’t miss any of Clifford’s other suspense novels, especially The Naked Runner (1966), a tale of intrigue behind the Iron Curtain that was made into a rather poor 1967 film with Frank Sinatra; A Wild Justice (1972), a tale of strife in Ireland told against the backdrop of a bleak Irish winter; and Goodbye and Amen (1974), which Ross Macdonald lauded as “an extraordinary thriller about several people of importance who are sequestered with an armed killer in a room of a first-class London hotel. It is intricately and brilliantly constructed, and written with tremendous drive and flair. Not only the ending surprises. There are surprises on nearly every page.”

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust