Sat 1 Nov 2025

A 1001 Midnights Review: WILLIAM CAMPBELL GAULT – Don’t Cry for Me.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews1 Comment

by Bill Pronzini

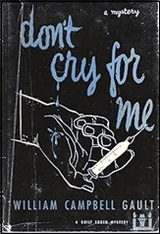

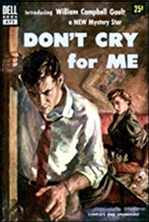

WILLIAM CAMPBELL GAULT – Don’t Cry for Me. Dutton, hardcover, 1952. Edgar Award winner for Best First Novel. Dell #672, paperback; cover art by James Meese.

Don’t Cry for Me is Gault’s first novel, and one of several non-series mysteries he wrote in the 1950s. His fellow crime novelist Fredric Brown had this to say about it: “(lt] is not only a beautiful chunk of story but, refreshingly, it’s about people instead of characters, people so real and vivid that you’ll think you know them personally. Even more important, this boy Gault can write, never badly and sometimes like an angel.” Gault’s other peers, the members of the Mystery Writers of America, felt the same: They voted Don’t Cry for Me a Best First Novel Edgar.

This novel (and many of Gault’s subsequent books) beautifully evokes the southern California underworld of drug dealers, addicts, hoodlums, racetrack touts, second-rate boxers, and tough-minded women with larcenous and/or homicidal proclivities. Its narrator, Pete Worden, is anything but a hero; he lives a disorganized and unconventional life, walking a thin line between respectability and corruption, searching for purpose and identity.

His girlfriend, Ellen, wants him to be one thing; his brother John — who controls the family purse strings — wants him to be another; and some of his “friends” want him to be a third. What finally puts an end to Worden’s aimless lifestyle is the discovery of a murdered man in his apartment, a hood named Al Calvano whom Pete slugged at a party the night before. Hounded by police and by underworld types, Worden is not only forced into his own hunt for the killer but forced to resolve his personal ambivalence along the way.

Don’t Cry for Me is first-rate — tough, uncompromising, insightful, opinionated, occasionally annoying, and altogether satisfying. An added bonus is a fascinating glimpse of the death of the pulp magazines (the primary market for Gault’s fiction for the previous sixteen years), as seen through the eyes of Worden’s neighbor and friend, pulp writer Tommy Lister.

Of Gault’ s other non-series books, the best is probably The Bloody Bokhara ( 1952), which is set in Milwaukee and has as its background the unique world of Oriental rugs and carpets. Also noteworthy are Blood on the Boards ( 1953), which has a little-theater setting; and Death Out of Focus ( 1959), about Hollywood film-making and script-writing.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.