Thu 26 Jan 2012

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review: MARGERY ALLINGHAM – Traitor’s Purse.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[3] Comments

by Thomas Baird

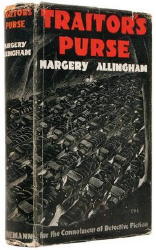

MARGERY ALLINGHAM – Traitor’s Purse. Doubleday Crime Club, US, hardcover, 1941. First published in the UK: Heinemann, hardcover, 1941. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback.

England is at war. The country is threatened by a catastrophic stroke, and time is desperately short. All lines of investigation have gone slack, and only one man knows the enormity of the situation. Only one man has the faintest clue to the heart of the conspiracy. As the story opens, Albert Campion awakes in a hospital bed with total amnesia from a blow to the head.

Hearing himself described as the killer of a policeman, he recklessly escapes and heads for the Bridge Institute, a research organization that is “a living brain factory.” The Masters of Bridge are a hereditary group who are the governors of the Institute, and Sir Henry Bull is one of the Senior Masters. When the secretary to the masters is killed, the police question Campion, who was the last man to see him alive.

Campion’s investigations are invested with the psychology of paranoia. He walks a tightrope, of sifting clues while trying to reestablish his memory. Stanislaus Oates, head of the CID, has disappeared, and Campion can’t confide his memory loss to his love interest, Amanda, because of her trust in him.

The only really practical help that comes his way is from his man, Magersfontein Lugg, who recognizes what a blow to the head can do and protects Campion from the police manhunt and from the gang of criminals on his track.

The search for the traitor weaves through the criminal conspiracy and the institute itself (and by extension into the government) and leads into the cavernous heart of Nag’s Head, the rocky headland that looms over the town of Bridge.

Many characters appear, disappear, and reappear throughout the saga, including friends and relations; the policemen Oates, Yeo, and Luke; and the spymaster L. C. Corkran.

This story is Campion’s trial by fire — afterward he is a changed man. Later in his career, he has less to do and becomes a sort of consultant.

After Allingham’s death, her husband continued the Campion adventures in three more novels. One novel that has received much critical approval, The Tiger in the Smoke (1952), in some ways seems overdrawn and overwritten.

Other recommended titles by Allingham are Mystery Mile (1930), Look to the Lady (1931), Sweet Danger (1933), and More Work for the Undertaker (1948). Inducements to read them include the memorable names of characters, both major and minor, and of the various settings. And if you’re a fan of that Golden Age staple, a proper plan or map of the scene, these provide cartographic delight.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.