Fri 27 May 2011

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS review: JIM THOMPSON – Pop. 1280.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[2] Comments

by Max Allan Collins

JIM THOMPSON – Pop. 1280. Gold Medal k1438, paperback original, 1964. Reprinted several times since, including Black Lizard, softcover, 1984, 1990. Filmed as Coup de Torchon (France, 1981).

The psychopaths of Jim Thompson’s novels — and his best novels invariably feature psychopathic protagonists — have much in common, but each is distinct. The closest Thompson comes to repeating himself is in Pop. 1280, where protagonist Nick Corey bears a great resemblance to Lou Ford of the better-known Killer Inside Me.

Like Ford, Corey is a law officer (a sheriff), and like Ford, he feigns folksy stupidity while committing cunning, vile, and often pointless murders — using his position as sheriff to cover them up.

The setting is a small southern river town before the turn of the century, and the flavor is at once reminiscent of Erskine Caldwell and Mark Twain; the latter influence is such that Corey at times seems a psychopathic Huck Finn.

Thompson is at his best here — on familiar ground, he seems almost to be having fun, not trying as hard to be an artist as he did in the sometimes uneven telling of Lou Ford’s story. Pop. 1280, a reworking of his most famous book, may well be his best. This is partially because Pop. 1280 is a black comedy; The Killer Inside Me is far too bleak for Lou Ford’s absurd behavior to approach the black humor that pervades the later novel.

Corey seems so picked on and put upon (by his shrewish wife Myra, among others) that the reader begins to root for this combination Li’l Abner/William Heirens. Also, Corey’s shrewdness — and sickness — dawns so gradually that the reader initially underestimates Corey — just as other characters in the novel have done.

By the end, Corey has come to the conclusion that he is Jesus Christ, but concludes also that being Christ doesn’t seem to be of any particular advantage.

Behind Thompson’s black humor is the notion that the human condition is so unpleasant as to drive each of us mad, at least a little. And perhaps, after identifying with or at least allowing ourselves to be confined within the point of view of a madman, we will understand the madness of, say, a Richard Speck — and the madness in ourselves — a little better.

An award-winning French film, Coup de Torchon (1981), directed by Bertran Tavernier, transplants Thompson’s tale to Equatorial Africa, 1936, but captures the spirit of the work to perfection.

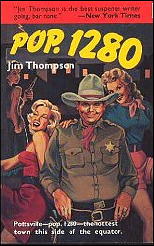

Tavernier’s film has helped draw attention to Thompson and Pop. 1280, and Black Lizard Books brought this minor masterpiece back into print in 1984, as one of a trio of Thompsons published in self-consciously old-fashioned “paperback” format, with covers evoking old pinball-machine art.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.