Wed 21 Jul 2010

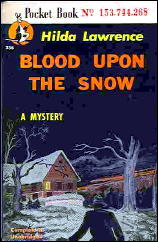

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS review: HILDA LAWRENCE – Blood Upon the Snow.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[4] Comments

by Marcia Muller:

HILDA LAWRENCE – Blood Upon the Snow. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1944. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition: February 1945. Reprint paperbacks: Pocket 336, February 1946; Avon Classic Crime PN320, 1970.

Hilda Lawrence wrote three novels featuring the odd investigative trio of private eye Mark East and spinster sleuths Bessie Petty and Beulah Pond. In addition, she published a melodramatic suspense novel, The Pavilion (1949), and two novellas, “Death Has Four Hands” and “This Bleeding House” (both 1950).

She is best known for the East/Petty/Pond books, and for good reason: They present an interesting juxtaposition of the hard-boiled school versus the little-old-lady sleuth, between the customs and mores of Manhattan and those of a small New England village.

The characters are well drawn, the setting evocative, and the interplay between Mark East and his elderly “Watsons” is entertaining.

As this first entry in the series opens, the snow is falling and Mark is arriving at the village of Crestwood. His introduction to Beulah Pond occurs when he stops to ask directions to the house where a prospective client expects him.

When he eventually arrives, he is told he must wait until morning for his interview; and when he meets with Mr. Stoneman, the old man seems to think he is hiring a private secretary rather than a private detective. Mark, however, senses something is very wrong in the house; the old man seems frightened and has a hurt wrist and bruises on his face.

He agrees to stay on for a few days, assuming secretarial duties, and makes it his first order of business to revisit Miss Pond, whom he perceives — rightly so — as a woman who knows a great deal about what goes on in the village.

When he arrives at her home, he is introduced to Bessie Petty, and the unlikely partnership in detection is launched.

The story that follows is one of slowly rising terror. The people with whom Stoneman is staying, Laura and Jim Morey and their two children, also seem disturbed; Stoneman is reported to have been sleepwalking; the housekeeper, Mrs. Lacey, has handed in her notice and seems upset about this; strange mischief has occurred in the wine cellar; and as the black winter night closes in, Mark remembers something Mrs. Lacey said about this being “good soil for evil.”

A slow-paced but absorbing chiller, as are the other two in the series — A Time to Die (1945) and Death of a Doll (1947).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.