Thu 17 Sep 2009

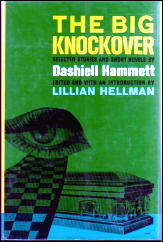

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS review: DASHIELL HAMMETT – The Big Knockover (1966).

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Pulp Fiction , Reviews[12] Comments

by Bill Pronzini:

DASHIELL HAMMETT – The Big Knockover. Edited and with an Introduction by Lillian Hellman. Random House, 1966. Paperback reprint: Dell, 1967, in two volumes: The Big Knockover and The Continental Op: More Stories from The Big Knockover. Also: Vintage V829, 1972.

Samuel Dashiell Hammett was the father of the American “hard-boiled” or realistic school of crime fiction.

As Raymond Chandler says in his famous essay “The Simple Art of Murder,” Hammett “wrote at first (and almost to the end) for people with a sharp, aggressive attitude to life. They were not afraid of the seamy side of things; they lived there. Violence did not dismay them; it was right down their street. Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse; and with the means at hand, not hand-wrought dueling pistols, curare and tropical fish. He put these people down on paper as they were, and he made them talk and think in the language they customarily used for these purposes.”

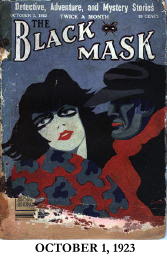

Hammett’s first published short story, “The Road Home,” appeared in the December 1922 issue of the pioneering pulp magazine Black Mask under the pseudonym Peter Collinson. The first “Continental Op” story was “Arson Plus,” also published as by Collinson, in the October 1, 1923, issue; the October 15 number contained “Crooked Souls,” another Op novelette and Hammett’s first appearance in the magazine under his own name. (“Arson Plus” was not the first fully realized hard-boiled private-eye story; that distinction belongs to “Knights of the Open Palm,” by Carroll John Daly, which predated the Op’s debut by four months, appearing in the June 1, 1923, issue of Black Mask.)

Two dozen Op stories followed over the ensuing eight years; the series ended with “Death and Company” in the November 1930 issue.

The Op — fat, fortyish, and the Continental Detective Agency’s toughest and shrewdest investigator — was based on a man named James Wright, assistant superintendent of the Pinkerton Detective Agency in Baltimore, for whom Hammett had worked. And his methods, if not his cases, are based on real private-investigative procedures of the period.

It was in these Op stories that Hammett honed his realistic style and plotting techniques, both of which would reach their zenith in The Maltese Falcon (1929).

The Big Knockover contains thirteen of the best Op stories, among them such hard-boiled classics as “The Gutting of Couffignal,” about an attempted hoodlum takeover of an island in San Francisco Bay, during which corpses pile up in alarming numbers and a terrific atmosphere of menace and suspense is maintained throughout; “Dead Yellow Women,” which has a San Francisco Chinatown setting and colorfully if unfortunately perpetuates the myth that a rabbit warren of secret passageways exists beneath the streets of that district; “Fly Paper,” in which the Op undertakes “a wandering daughter job,” with startling results; “Corkscrew,” a case that takes the Op to the Arizona desert in an expert blend of the detective story and the western; and “$106,000 Blood Money,” a novella in which the Op sets out to find the gang that robbed the Seaman’s National Bank of several million dollars, and does battle with perhaps his most ruthless antagonist.

Lillian Hellman’s introduction provides some interesting but manipulated and self-serving material on Hammett and his work.

This is a cornerstone book for any library of American detective fiction, and an absolute must-read for anyone interested in the origins of the hard-boiled crime story.

The Continental Op appears in several other collections, most of which were edited by Ellery Queen and published first in digest-size paperbacks by Jonathan Press and then in standard paperbacks by Dell; among these are The Continental Op (1945), The Return of the Continental Op (1945), Hammett Homicides (1946), Dead Yellow Women (1947), Nightmare Town (1948), The Creeping Siamese (1950), and Woman in the Dark (1951).

The most recent volume of Op stories, The Continental Op, a companion volume to The Big Knockover but edited and introduced by Stephen Marcus instead of Hellman, appeared in 1974.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Editorial Comment: Coming over the four days, spread out at a rate of one a day, will be reviews by Bill Pronzini and Mike Nevins of The Dain Curse, The Glass Key, The Maltese Falcon, and The Thin Man, all taken from 1001 Midnights.