Tue 18 Aug 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS review: A. A. FAIR – Owls Don’t Blink.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[11] Comments

by Marcia Muller:

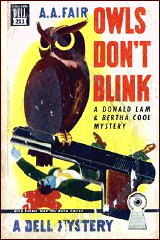

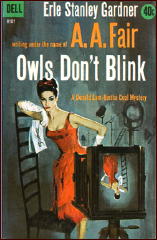

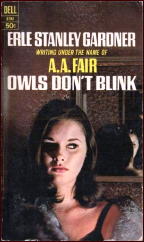

A. A. FAIR – Owls Don’t Blink. New York: William Morrow, hardcover, 1942. Paperback reprint: Dell 211, mapback, 1948. Many other reprint editions in both hardcover and soft.

A. A. Fair is a pseudonym of Erle Stanley Gardner, but don’t pick up one of these novels featuring private eyes Bertha Cool and Donald Lam expecting a couple of carbon copies of Paul Drake.

Cool and Lam are an amusing and endearing pair — perfect foils for one another. Bertha Cool, at the time of this novel, is the middle-aged proprietor of an L.A. investigative firm, pared down to a mere 165 pounds but ever on the alert for a good meal. Her partner, Donald Lam, is a twerp in comparison — young, slender, and forever on the defensive for what Bertha considers excessive squandering of agency money.

But there’s considerable affection between the two, and with Donald doing the legwork, they crack some tough cases — and have a lot of fun while doing so.

Owls Don’t Blink opens in the French Quarter of New Orleans, where Donald is occupying an apartment once rented by a missing woman he has been hired to find. He is due to meet Bertha at the airport at 7:20 the next morning and knows there will be hell to pay if he’s late.

Fortunately, he arrives on time, and together they meet the New York lawyer who has hired them to find Roberta Fenn, a former model. Over a number of pecan waffles — a number for Bertha, that is, who “only eats once a day” — the lawyer is evasive about why he wishes to locate Miss Fenn. But Cool and Lam proceed with the case — and Bertha proceeds with several lavish meals, still on that same day.

The discovery of the missing woman’s whereabouts proves all too easy, and also too easy is the discovery of a corpse in Roberta Fenn’ s new apartment. But from there on out, everything’s as convoluted as in the best of the Perry Mason novels.

The scene moves from New Orleans to Shreveport, Louisiana, and from there to Los Angeles, where its surprising (although possibly a little out-of-leftfield) conclusion takes place.

And there’s a nice twist in the Cool-Lam relationship that will make a reader want to read the later entries in this fine series, such as Crows Can’t Count (1946), Some Slips Don’t Show (1957), Fish or Cut Bait (1963), and All Grass Isn’t Green (1970). Especially entertaining earlier titles are The Bigger They Come (1939) and Spill the Jackpot (1941).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.