Sat 7 Jun 2014

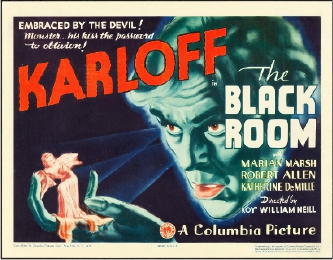

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: THE BLACK ROOM (1935).

Posted by Steve under Horror movies , Reviews[8] Comments

THE BLACK ROOM. Columbia Pictures, 1935. Boris Karloff, Marian Marsh, Robert Allen, Thurston Hall, Katherine DeMille. Director: Roy William Neill.

The Black Room, although not as well known as the classic Universal Studios horror films from the same era, is a taut, suspenseful, and visually crisp Gothic thriller starring Boris Karloff. In a memorable performance that demonstrates his strength as an actor, Karloff portrays two twin brothers, the evil, dissolute Gregor and the charmingly naïve Anton, the last remaining members of the de Berghmann family.

Directed by Roy William Neill (best known for directing some of the Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce Sherlock Holmes movies), the film makes skillful and economical use of decorative settings, shadowy lighting, unique camera angles, and repetitive music to convey a sense of impending doom and otherworldliness. As Joe Dante accurately notes, there is a fairy tale quality to The Black Room. The majority of film takes place in a castle, there’s horses and carriages a plenty, a prophecy fulfilled, and a beautiful maiden endangered by a madman and his demonic love for her.

The plot is fairly straightforward. We’re transported to a dreamlike land somewhere in central Europe. Twin brothers, Gregor and Anton, are born and their father, patriarch of the de Berghmann dynasty, isn’t happy about it. Not without good reason, for there’s a prophecy that holds that, when twin brothers are born in the family, the younger brother will end up killing the older one.

Specifically, it’s been written that younger brother kill commit fratricide in the black room, the castle’s oubliette. Although they are twins, we learn that Gregor is one hour older than his brother Anton, who was born with a paralyzed right arm. (How else would we tell them apart?) The stage is set for mystery and murder.

Fast forward twenty years. We learn that the disheveled Baron Gregor (Karloff) is a brute, a dissolute tyrant in a castle keeping busy by oppressing the peasants and violating their women. The townsfolk have had just about enough, but they aren’t quite sure how to get rid of the mad baron. Assassination attempts have been made on his life.

Enter twin brother, dapper and naïve Anton, also portrayed by Karloff, who returns to his hometown after traveling in Europe. The two brothers reunite. After killing Mashka (Katherine DeMille) who witnessed his criminal acts, evil brother Gregor abdicates and turns power over to Anton, but not for long. Gregor lures Anton into the eponymous black room, pushes him down into a pit where he dies, a knife resting between his body and his right arm.

This is when Karloff’s skill as an actor really shines through. Now, he’s portraying a third character, as it were: evil Gregor pretending to be Anton. The murdering nobleman has his sights set on the beautiful, white-clad Thea (Marian Marsh, often bathed in a soft white light), niece of Colonel Hassell (Thurston Hall).

But she’s not in love with the baron. Her heart belongs to the upstanding Lt. Lussan (Robert Allen) who ends up being convicted for the murder of Col. Hassell, a murder that Gregor-as-Anton commits when the colonel unmasks his true identity. If it sounds somewhat complicated, trust me when I say it’s really not.

Karloff is a skilled enough actor to pull off these three distinct roles. Roy William Neill’s direction gives the viewer enough time and visual cues to easily follow what’s happening every step along the way, including in the final showdown where the prophecy is indeed fulfilled after a dog forces Gregor-as-Anton to use his right arm, demonstrating to everyone that he’s an imposter.

The Black Room has some particularly notable camera work, which makes the film significantly better than many other horror films from the same era. Most of the time, the viewer is not on the same eye level as are the characters. Often times, the actors are shot from angles either significantly beneath them, even at foot level, or above them. This gives the impression that we are meant to be conscious of our role as spectators, peering through the looking glass into a fantastic realm. Look, also, for the scene in which the camera looks up at Anton right before his brother pushes him down into the pit.

The film, perhaps not surprising in a movie about twin brothers, also makes ample use of mirrors and reflections. For instance, the first we see of Gregor immediately after he murders Mashka is as a reflection a mirror, shot at an angle. There’s also a great soliloquy in which Gregor-as-Anton talks to himself in a mirror and an eerie scene in which Gregor talks to himself in a reflection in the black room.

The film repeatedly juxtaposes faith with superstition. There are numerous scenes with crosses and crucifixes, both in and out of a graveyard. Likewise, there are two important scenes in which Thea and Lt. Lussan have intense discussions in front of Virgin Mary statues. As far as superstition, there is not only the matter of the prophecy, but also a black cat – one real and one made of wood – that shows up in the film. It’s worth looking out for.

In conclusion, The Black Room is one of those forgotten gems of 1930s cinema. It may not be a classic, but in many ways it’s as good as many of the best known Universal films from the same era and far better than the Universal B-films from the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Karloff is on the top of his game here. There’s one scene in which he as Gregor is holding a knife and talking to himself as he carves a pear, demonstrating just how crazed and inattentive he is. That’s the type of acting that makes the film really worth watching. The story, while not the most creative, is not bad either.