REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

KONGO. MGM, 1932. Walter Huston, Lupe Velez, Conrad Nagel, Virginia Bruce, C. Henry Gordon. Director: William J. Cowen.

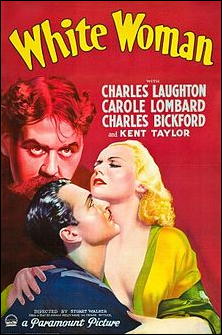

WHITE WOMAN. Paramount, 1933. Carole Lombard, Charles Laughton, Charles Bickford, Kent Taylor, Percy Kilbride. Director: Stuart Walker.

Caught a couple of of lush tropical melodrama-cum-horror flcks a few weeks back; both are based on stage plays and both quite fun.

Kongo is a sweaty, steamy, depraved-looking thing, with Walter Huston… well, I almost said he was in excellent form, but here he plays a paraplegic, confined to a wheelchair and determined to wreak baroque vengeance on the man who put him there (a role he played on Broadway before Lon Chaney took it up in the film west of Zanzibar).

To this end, he has set up a trading post in the African jungle, where he cows the natives with stage magic, helped along by Lupe Velez, who radiates her own steam, thank you very much.

Houston wriggles about the place like a grimy spider, moving his victims about like game-pieces, marking the days till he springs his trap on a calendar scrawled iver with the words “HE SNEERED!”

This could be corny stuff, all right, but everyone plays it to the edge without tripping over. Director William Cowen (who he?) keeps things moving right along and handles the crucial scene — a satisfying and improbable twist that reverses everything we thought was happening — without blinking at the old-fashioned melodrama, and Harold Rosson photographs with what looks like s sheen of sweat over it all.

Even normally uninspired actors like Conrad Nagel and Virginia Bruce put it across quite well. In all, a movie to set aside your critical faculties and simply enjoy.

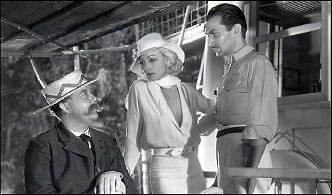

White Woman tiptoes through similar tropical tulips, and does it quite neatly, thanks mostly to a script by Frank Butler that keeps things edgy and unpredictable, pacey direction from Bluert (Werewolf of London) Walker, and the usual Paramount patina of soft-focus splendor.

There’s moody acting from Carole Lombard as the eponymous “entertainer” who winds up in a remote rubber plantation, Charles Bickford, Kent Taylor, and Charles Middleton, as lost souls slaving away in the heat, but the film belongs to Charles Laughton, who plays the jungle tyrant, and plays it for laughs — which makes a nasty part somehow more disturbing.

Made up with frizzy hair and a silly moustache, Laughton gads about in a stripes, plaids and polka-dots, inflicting one deliberately sick joke after another on his unwilling workers, oblivious to the mounting tension until he sets off a tribal uprising (in hilarious fashion) and tries to deal with the bloody outcome.

Where Kongo seems deliberately theatrical, Woman keeps undercutting the melodrama with surprising bits of business from characters who stubbornly refuse to play by the rules of the genre: Laughton in particular is constantly faced with dramatic outbursts, only to respond as if he wasn’t even in the same movie, kidding around with an unnerving humor about as funny as Richard Widmsrk’s laugh.

The result is that rarity, an old-fashioned tale that keeps one wondering what’s coming next.