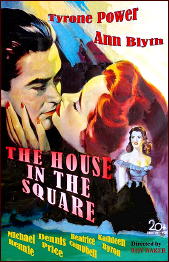

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

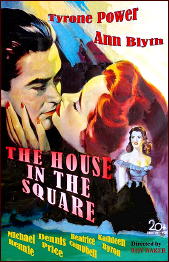

I’LL NEVER FORGET YOU. 20th Century-Fox, 1951; aka The House in the Square (British title). Tyrone Power, Ann Blyth, Michael Rennie, Dennis Price, Beatrice Campbell, Raymond Huntley. Screenplay by Ranald MacDougall, based on the play Berkeley Square by John Balderston. Director: Roy Ward Baker.

This is an old favorite of mine that is available for the first time on DVD. It’s based on the hit play Berkeley Square which was filmed earlier with Leslie Howard, and once I start to discuss it, the plot will seem familiar. It has been used countless times, but this is based on one of the original sources.

In this version, Power is Peter Standish, a nuclear physicist in England working on a secret project. His work and the birth of the atomic age have left him a lonely man, and one rather fed up with this world and this time. When he meets Roger Forsyth (Michael Rennie), they hit it off, and he learns that Forsyth’s old family home was destroyed in the Blitz but some of it still stands. He agrees to meet Forsyth to see the old place that stood in fashionable Berkeley Square.

Arriving before Forsyth, but after dark, he feels a strange tie to this place. A sense of déjà vu as if he had been here before. Wandering through the ruins he spots a surviving portrait still hanging over the remains of a hearth.

The painting is of a beautiful woman and mesmerizes him. But when he moves on, he upsets some of the rubble and is knocked unconscious.

And when he wakes up, he is in England of the 18th Century, the age of the Enlightenment and the birth of the modern scientific age. And by the way the film is suddenly in brilliant technicolor instead of the drab black and white of the introduction. Cinematic shorthand for how Power views his own world and time and the past as he sees it.

Nothing new, the technique was used most famously in The Wizard of Oz and both Portrait of Jennie and Hitchcock’s Spellbound used color briefly for it’s visual qualities.

He meets Forsyth’s ancestor and the girl in the portrait, Ann Blyth, with whom he is already half in love, the wife of wastrel Tom Pettigew (Dennis Price).

Passing himself off as a Colonist to explain his accent, he puts his talents as a scientist to work to become something of a sensation with his wonders, but he draws too much attention, is accused of witchcraft, and is nearly killed.

When he comes to he is again in postwar drab black-and-white England, having been found by Forsyth and his sister — Martha (Ann Blyth). The look between the two is enough to tell you that love has survived across time and they will finally be joined together.

Music rises, fade out …

This sort of romantic nonsense has been knocking around for quite a while. It’s pretty much the theme of George DuMaurier’s Peter Ibbetson, is touched on by some of Marie Corelli’s novels, is part of the fascination of Rider Haggard’s She, and shows up in novels like Edwin Lester Arnold’s Phra the Phoenician. John Dickson Carr used it in one of his best historical mysteries Fire Burns and to some extent in The Burning Court.

For that matter it is pretty much how Edgar Rice Burroughs John Carter gets to Mars — a combination of wish fulfillment Madame Blatavasky, Theosophy, reincarnation, and the whole fascination with the occult that played such a role at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th Century. Love conquers all and survives even death.

As late as Richard Matheison’s Somewhere in Time it still enthralled audiences as Christopher Reeve and Jane Seymour struggled with love across time and past lives.

I’ve never seen Berkeley Square (1933), so I can’t say if this is as good a telling of the tale as the Leslie Howard film. It’s simply one I’ve seen perhaps a dozen times since I was a child, and it has always touched some chord with me.

It may seem at best a rather tired fantasy to you, and that’s fine. But if you let it, the film has a charm all its own. Similar films include Enchantment with David Niven and even the Archers’ Stairway to Heaven, and the musicals Brigadoon and to a lesser extent Finian’s Rainbow.

I confess I’m a sucker for them all. Probably my Highlander ancestors. All that Scotch and fog — you tended to see things. Cynical realists are warned to stay away.

But if you ever one day dreamed of a another time or wanted to escape into a more romantic and less mundane world this is a good vehicle for it. It’s a bit like Shangri La, Brigadoon, or even forgotten Kor, it’s there to be found if only in your heart.

I make no excuse for it as film art. It is quite simply a movie I love, whatever its flaws or failures, and there are few enough of those for any film lover.

Note: The 1933 version was directed by Frank Lloyd with Leslie Howard, Heather Angel, and Samuel S. Hinds. And anyone familiar with their Noel Coward will know the pronunciation is Barkley as in his popular song “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square” that became a sort of anthem for WW II England.