Wed 24 May 2023

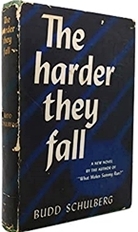

A Book! Movie!! Review by Tony Baer: BUDD SCHULBERG – The Harder They Fall // Film: 1956.

Posted by Steve under Films: Drama/Romance[5] Comments

BUDD SCHULBERG – The Harder They Fall. Random House, hardcover, 1947. Paperback reprints include Bantam 707, October 1949, and Signet, 1968.

THE HARDER THEY FALL. Columbia Pictures, 1956. Humphrey Bogart, Rod Steiger, Jan Sterling, Mike Lane, Max Baer, Jersey Joe Walcott, Edward Andrews, Harold J. Stone, Carlos Montalban, Nehemiah Persof. Screenplay by Philip Yordan, based on the novel by Budd Schulberg. Directed by Mark Robson.

Eddie Lewis is press agent for the boxing interests of mob boss Nick Latka. Eddie still has some fantasies about being a ‘real’ writer someday. But for now, he’s getting paid a lot of dough and a percentage to hype up whatever fighter the mob tells him to.

His newest assignment, however, promises to be harder that all of the others: hyping Man Mountain Toro Molina, Giant of the Andes (based on real life ‘boxer’ Primo Carnera). Molina (as well as Carnera) is 6’7â€, 275 pounds. Slow as sludge, with a glass jaw and punches that couldn’t puncture a balloon.

Molina is a pituitary case, with a body enlarged by glands and muscle bound by a life of lifting wine barrels in Argentina.

Eddie expresses his concerns about hyping this oafish goon. But Nick, the Boss, reassures him (reminiscent of William Randolph Hearst’s “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the warâ€) you hype the fighter, I’ll make sure he wins the fights.

From there it’s one fixed fight after another, building up the hype machine, praying on the gullibility of the average fan and the salability of the average reporter.

And then, when he finally meets a legit fighter that can’t be bought (Max Baer — both in reality in the Max Baer/Primo Carnera fight as well as in the film where Max Baer reprises his role as destroyer of fake fighters), the mob is happy enough to take the 9-5 odds and lay their money on Baer for the win. Carnera/Molina is decimated in the Max Baer fight (in the book he’s named Buddy Stein — in the film Buddy Brannen).

The book qualifies as noir. There’s nothing redemptive. The whole thing stinks to high heaven. Even the pummeling of Molina is such an absolute decimation and destruction of a basically decent, stupid ox that there’s no schadenfreude to enjoy. Everyone is bought and sold. And after the fight, when ‘El Toro’ decides he’s ready to quit and go home, he’s told that after subtracting all expenses that his total take (for his entire boxing career) amounts to $49.70.

In the film, when Bogart finds out about this affront to human decency, he gives his entire take to Molina ($16,000). In the book, Eddie Lewis only offers Molina $5,000 — which makes a lot more sense as Eddie does everything in half-measures. In the book, Molina rejects the filthy lucre. In the film, Molina gratefully accepts: At least the world has one true friend!

In the book, Eddie’s girlfriend dumps him: sick of his hypocrisy and his pretense of being better than the trash he traffics. In the film, Eddie is married and his wife stands by his side, nudging him lovingly towards truth, justice and the America Way.

The book ends with Eddie in bed with a whore. The movie, with Bogart standing up to corruption: The Harder They Fall in the film is a double entendre referring both to the collapse in the ring of Man Mountain and to Eddie’s outing of mafia corruption in the Free Press! Eddie’s gonna singlehandedly bring down mafia fight fixing! Bogart reprises his role of Rick in Casablanca. Bogart’s corruption is only a pose. Deep down he’s clean and pure and strong. The final image has his devoted wife placing a tea cup and saucer lovingly beside his Remington as he types his expose.

It’s Bogart’s final role. He looks much older than his 56 years, weak and tired and full of cancer. He tries to convince us that good will prevail, and the swelling orchestra backs him up. But he looks resigned and deathly, like the truth.

—————–

What did I think of them? Well — like I said: the book is noir and the movie isn’t. But just because something is noir or not doesn’t mean it’s good. For me, they both hit me kind of flat. If you’re interested in the basic story it’s pretty much covered in the movie (until the truth is betrayed in the end to allow the audience to leave with a smile and comfort in the fact that all is well and justice will out).

The movie also leaves out a tremendous amount of sex. More sex than I knew was possible in print in 1947. (Eddie says trying to remember one girl over another is like trying to remember one particular cigarette after you just chain smoked a pack.) El Toro has an affair with the mafia boss’s wife — until he catches her giving a blow job to the chauffeur’s 17-year old nephew (were only the chauffeur the beneficiary I’d make my annual Rosh Hashanah joke about blowing the shofar): ‘La puta! La puta!’ he screams at her.

The movie also pretty much leaves out the mob element. Although Rod Steiger is a tough guy, it’s not really clear that the repercussions of not going along with his orders are ending belly up in the East River. You’ll merely be fired. (As an aside, if you close your eyes, Steiger’s voice and words sound like a dead ringer for Donald Trump — I’d be shocked if Trump didn’t watch the film when he was a 10 year old boy).

Anyway. I guess I’d say you can safely skip both the film and the book. They’re okay. But, as good old Robert Louis Stevenson jauntily jotted: ‘the world is so full of a number of things, I’m sure we should all be as happy as kings.’