Wed 12 Jan 2022

A Movie Review by Dan Stumpf: A CANTERBURY TALE (1944).

Posted by Steve under Films: Drama/Romance , Reviews[7] Comments

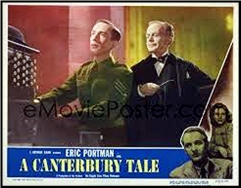

A CANTERBURY TALE. Archer, UK, 1944. Eric Portman, Sheila Sim, Dennis Price, John Sweet, Esmond Knight, H.F. Maltry, and Eliot Makeham. Written & directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressberger.

I watched this twice, back to back, just to see if I’d missed something. When I was through, I told the leggy red-head next to me on the couch that I still wasn’t sure how A Canterbury Tale felt about itself.

“Do movies think about themselves?†she asked.

Well, every movie has an attitude, even if it’s just give-a-damn, and Canterbury’s attitude is mostly one of a cherished England, rich in heritage and humanity. But there’s also a disturbing sub-text that moves the film, like many another Powell/Pressberger work, from the realm of simple propaganda into the rare class of Weird Movies.

Made in the fifth year of a World War, confused, diffuse, and at times quite powerful, Canterbury concerns itself with conditions on England’s home front, bizarre crime, and the problems of three ordinary people caught up in it all.

Price and Sweet play Sergeants — British and American, respectively — and Sim is a Land Girl detailed to work for local JP Thomas Colpepper (Eric Portman) in a village just outside Canterbury. But as the sergeants escort her from the train station to the town hall (It’s night and the village is under Blackout orders.) a shadowy figure darts out of the darkness and… and…. and…..

Pours glue on the lady’s head. Yeah. Well, I told you there was bizarre crime here. Someone’s been making rather a habit of this sort of thing (Wait till you hear the motive!) picking on young ladies out after dark with soldiers, and Ms Sim is only the latest victim.

But not a passive one. She and the sergeants pursue the miscreant into the Town Hall, where the local police (“The Glue Man’s at it again!â€) search the building and, in a moment worthy of Caligari, discover only Colpepper, the all-powerful JP, seated magisterially in his inner sanctum.

Of course the locals refuse to believe that a man of Colpepper’s stature could possibly be the Glue Man, so it falls to our intrepid trio to uncover evidence of his guilt and take it to the authorities in Canterbury.

The ensuing story moves far too slowly, with way too many digressions, but the amateur sleuths carry it along by dint of their sheer charm and inefficiency. And they get their act together just in time for a tense and surprising confrontation in a railway carriage compartment on a train bound for Canterbury.

And then they reach Canterbury, and all my notions about this movie got blown to pieces.

It’s a powerful and moving finale, and one that left me considerably upset. Perhaps I shouldn’t look at it from a contemporary perspective, but to my mind pouring glue on ladies’ hair and running off into the night are acts of misogyny and cowardice. I’ll just say A Canterbury Tale doesn’t share my point of view, and leave it at that.

A final note: this was to all intents and purposes the only film appearance of John Sweet, an amateur actor chosen for his total freshness in the part of the American Sergeant. It was a good choice.