Thu 6 Nov 2025

SF Diary Review: PIERS ANTHONY – Sos the Rope.

Posted by Steve under Diary Reviews , Science Fiction & Fantasy[7] Comments

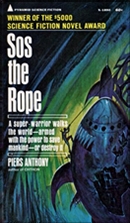

PIERS ANTHONY – Sos the Rope. Pyramid X-1890. Paperback original; 1st printing, October 1968. Cover art by Jack Gaughan. Serialized earlier in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, July-Aug-Sept 1968, Collected in Battle Circle (Avon, paperback, 1978).

A strange triangle formed between two men and a woman becomes the key to the future of a post-war semi-feudal society, There are the warriors whose problems are solved by the force of arms, by trial by combat. And there are the crazies, who supply the traditions of learning and the past.

Any form of unifying leadership is discouraged by the secret underground manufacturers of all supplies, and it is Sos’ friend Sol who threatens to provide that leadership, with the help of Sos, which would upset the balance of this precarious society. Sola is the wife of Sol, who bears the daughter of Sos. And it is Sos who is sent to end Sol’s leadership, and who then becomes the one who must be destroyed, What he has built, he must also destroy.

A dilemma, unresolved. To strive for the benefits of civilization again, or to maintain the present because with it civilization brings destruction? What to do with an empire that cannot withstand those who have the power and wish to keep it for themselves?

Much much more than for Lin Carter’s “swords and sorcery.”

Rating: *****