Sat 9 Apr 2022

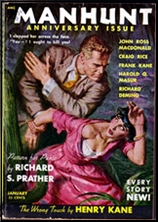

PI Stories I’m Reading: RICHARD S. PRATHER “The Guilty Party.â€

Posted by Steve under Stories I'm Reading[5] Comments

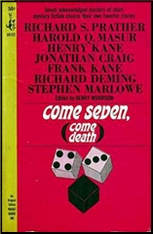

RICHARD S. PRATHER “The Guilty Party.†Short story. PI Shell Scott. First published in Come Seven, Come Death, edited by Henry Morrison (Pocket, paperback original, 1965). Collected in The Shell Scott Sampler (Pocket, paperback original, 1969).

Shell doesn’t have anything close to a major crime to solve in this one, and a full page of its full thirteen is taken up in describing his newest client, from the top of her head to her toes. She’s quite an eyeful, and Shell doesn’t know whether to ogle, leer, or just outright stare:

It also turns out that she is quite wealthy, in the multi-million dollar range,

So why has she come to hire Shell Scott? It turns out that a small metal device fell out from under her bed when got up that morning. Shell quickly deduces that it was a listening device of some kind. A bedbug, if you will. Who could have put it there? The only person who’s been in Lydia’s apartment recently is her fiancé.

If nothing else, Shell knows a cad when he sees him, or in this case, learns about him.

Once in Lydia’s apartment, he puts on a show for her, bouncing up and down on her bed, yelling YOWZA! (I’m paraphrasing), while she’s yelling back, STOP! and WHAT ARE YOU DOING? And he replies, DARLING!!

It’s one way to flush out a cad when you need to in a hurry.

Obviously this is a very minor effort, but it’s also exactly what devout readers of Shell Scott’s wackier adventures had come to expect, and it’s also exactly what they got.