Sat 7 Jan 2012

Characters from DFW #10: OSCAR VAN DUYVEN & PIERRE LEMASSE — by Monte Herridge.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Characters , Columns , Pulp Fiction[6] Comments

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by MONTE HERRIDGE

#10. OSCAR VAN DUYVEN & PIERRE LEMASSE, by Robert Brennan.

Oscar van Duyven & Pierre Lemasse appeared in a short series of ten stories by Robert Brennan that were published in Flynn’s Weekly Detective Fiction between 1926 and 1927. The series involves the adventures of a pair of men who wander the French countryside looking for matters of interest. They usually find mysteries to solve.

Oscar van Duyven is an American millionaire from New York, owner of an electric fan corporation. Pierre Lemasse is from Paris, France, and is the companion to the millionaire. Lemasse is younger than van Duyven and is the more mystery oriented person. He has a knack of finding clues and matters of interest in the various cases the two are involved in.

Van Duyven usually goes along with what Lemasse wants, although Lemasse is described as his assistant and is the driver of van Duyven’s automobile.

In the first story in the series, “The Maltese Cross,†the pair are on the French coast doing nothing in particular when a mystery arises. From an island just off the coast a man escapes from the prison on it, and from a French coast town opposite a wife disappeared the same day. Lemasse finds all sorts of interesting facts and clues about the events, and ties the two disappearances together. Still, a somewhat disappointing debut.

The second story in the series, “Pierre Rides the Storm,†is a direct sequel of the first story and continues the story of the escaped convict, Bruneau. He is caught in the severe storm that hit the French coast, and van Duyven and Lemasse endeavour to rescue him from the stranded ship in which he tried to make his escape.

The third story, “A Murderer’s Refuge,†continues the story of Bruneau the escaped convict. This time van Duyven and Lemasse are in Spain, and have brought Bruneau with them in order to ask the local church for sanctuary for him.

The two men then go to Avignon in France to investigate the crime Bruneau supposedly committed. While there Lemasse quickly solves the case and clears Bruneau. A bit of an anti-climax with the solution literally falling into their laps.

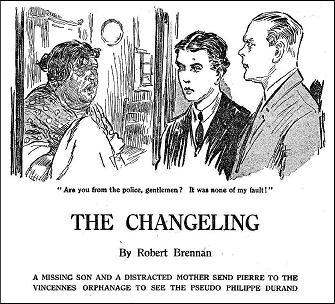

The fourth story, “The Changeling,†is a new story and self contained without any continuations. The two “investigators†are appealed to for help in locating a missing child. The child not only is missing, but a different child was substituted in his place. Lemasse tracks down the missing child and restores him to his mother.

The following story is “Blind Lanneau,†which concerns the murder of a blind peddler. The two investigators are still in France. This story is anticlimactic, because Lemasse discovers the murderer early in the story, and a lot of space is taken up by the murderer telling his own story (which includes what happened years before).

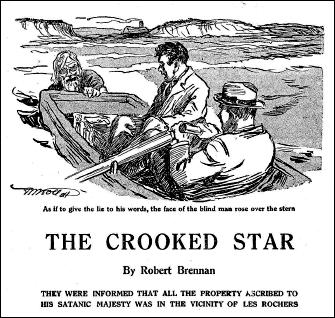

The next story, “The Crooked Star†is a sequel to the previous one. This one involves the two investigators looking for a hidden treasure using a cipher the murderer from the previous story had given them before he died.

Blind Lanneau, who was mentioned and discussed in the previous story but not seen, shows up in this story to compete with them for the treasure. Some deductions and deciphering of the cipher sheet is performed by the two as the story progresses.

“The Highwayman†comes next, and is a sequel to the previous one. Having lost the treasure when their boat sank, the two investigators suddenly find themselves the target of a criminal who wants the treasure and thinks they have access to it. Suddenly Blind Lanneau pops up who also wants the treasure and is searching for it.

“The Little Angels†refers to a French street gang who are extremely vicious. When a newspaper editor named Maurice Duverne writes an editorial against the gang and is immediately attacked, there is public outrage against the gang. The police move in to the district and clean out the gangsters. However, Lemasse is not convinced the gang committed the attack, and induces van Duyven to help him investigate.

“The Fugitive Footman†is probably the best story in the series. The two investigators come across a man in distress. They agree to help him, learning that the man is Bernard, a footman at the Deauville mansion. Deauville has just been murdered, and the footman is running away because he is accused of the crime.

The two investigators go to the Deauville mansion, where they find an inspector named Croissart in charge of the case. Croissart is an old friend of theirs, and relates the facts of the case. Lemasse sees more than meets the eye, and deduces the real murderer and the motive.

“Two Chests of Gold†is a direct sequel to the previous story, and involves the chests that were a part of that story. Now there is a search on for the missing chests, also involving a Scotland Yard man who asks van Duyven and Lemasse for their assistance.

This is an average series, with some good stories, but mostly average. There is no element of humor in the stories. The series is of interest to those interested in simple detective stories.

The problem I have with this series is that Lemasse makes all of his deductions and discoveries and clues seem overly simple. There is very little complexity to the series. The closest it comes is the cipher in “The Crooked Star.â€

The Oscar van Duyven & Pierre Lemasse series, by Robert Brennan:

The Maltese Cross July 31, 1926

Pierre Rides the Storm August 7, 1926

A Murderer’s Refuge August 14, 1926

The Changeling August 21, 1926

Blind Lanneau September 4, 1926

The Crooked Star September 11, 1926

The Highwayman September 18, 1926

The Little Angels December 18, 1926

The Fugitive Footman January 1, 1927

Two Chests of Gold January 15, 1927

Previously in this series:

1. SHAMUS MAGUIRE, by Stanley Day.

2. HAPPY McGONIGLE, by Paul Allenby.

3. ARTY BEELE, by Ruth & Alexander Wilson.

4. COLIN HAIG, by H. Bedford-Jones.

5. SECRET AGENT GEORGE DEVRITE, by Tom Curry.

6. BATTLE McKIM, by Edward Parrish Ware.

7. TUG NORTON by Edward Parrish Ware.

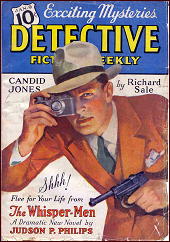

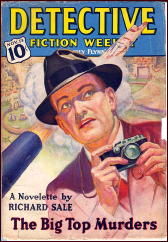

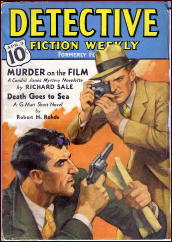

8. CANDID JONES by Richard Sale.

9. THE PATENT LEATHER KID, by Erle Stanley Gardner.