Wed 21 Jul 2010

Mike Nevins on BEFORE MIDNIGHT, ELLERY QUEEN, PETER CHEYNEY and the “Bezuzus.”

Posted by Steve under Authors , Collecting , Columns , Covers , Mystery movies[26] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

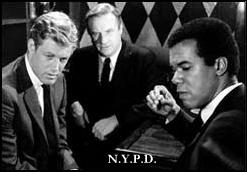

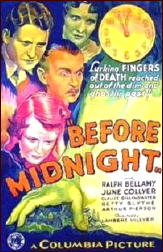

Thanks to Turner Classic Movies I recently discovered a detective film series I had never heard of before. Before Midnight (RKO, 1933) debuted on TCM in June and starred a young Ralph Bellamy as Inspector Trent of the NYPD.

A procedural this ain’t: Trent comes out on a dark and stormy night to a Toad Hall fifty miles from New York City at the request of a millionaire who expects to be killed before the ancestral clock strikes twelve. Sure enough, the murder takes place, and Trent immediately takes over the investigation, such as it is, smoking up a storm as he interrogates the dead man’s lovely ward, the doctor who loves her, the enigmatic Japanese butler, the sleazy lawyer, etc. etc.

Eventually, donning a white lab coat for forensic cred, he holds up two test tubes with blood samples in them and announces to his bug-eyed stooge that both came from the same person. How he managed to do that, generations before anyone ever heard of DNA, remains a mystery after the murder method (obvious to most viewers) and the murderer (obvious to all) are exposed.

A bit of Web surfing taught me that Before Midnight was the first of four Inspector Trent films, all starring Bellamy and dating from 1933-34. The titles of the other three are One Is Guilty, The Crime of Helen Stanley and Girl in Danger.

Columbia had released an earlier detective series with Adolphe Menjou as Anthony Abbot’s Police Commissioner Thatcher Colt but had dropped it after two films. The Trent series lasted twice as long but who today has ever heard of it? Bellamy of course went on to star in Columbia’s bottom-of-the-barrel series of Ellery Queen films (1940-41).

Second of the four EQ films with Bellamy in the lead was Ellery Queen’s Penthouse Mystery (1941). For most of my life I was unsure whether this picture was based on any genuine Queen material.

In Royal Bloodline I speculated that it might have come from one of the early Queen radio plays. Recently I learned that my hunch was right. Its source was the 60-minute drama “The Three Scratches†(CBS, December 13, 1939).

Someday I’d love to compare the Dannay-Lee script with the infantile novelization of the film by some anonymous hack that was published as a tie-in with the movie, but unfortunately that script was not included in The Adventure of the Murdered Moths (2005).

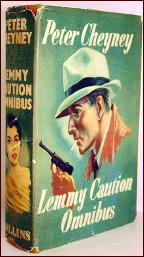

Does the name Peter Cheyney ring any bells? He was an Englishman (1896-1951), the son of a Cockney fishmonger who specialized in whelks and jellied eels.

He had never visited the U.S. but in 1936 began writing a long series of thrillers narrated in first person by hardboiled G-Man Lemmy Caution, beginning with This Man Is Dangerous (1936).

For the most part these quickies were laughed off as unpublishable over here but became huge successes in England and also in France, where translation concealed Cheyney’s habit of peppering the dialogue of American characters with British slang, not to mention self-created idioms which are like nothing in any language known to humankind.

The one that has stuck in my mind longest is “He blew the bezuzus,†which is not a musical instrument but just Cheyney’s way of saying “He spilled the beans.â€

According to Google the only known use of the word was in Sinclair Lewis’s novel Babbitt, where a character is said to have a degree from Bezuzus Mail Order University.

Could Cheyney have read that acerbic satire on the American middle class or did he come up with the word independently? Googling “bezuzus†with Cheyney’s name produces no matches, but I suspect that situation will change as soon as this column is posted.

With The Urgent Hangman (1938) Cheyney launched a series of utterly conventional ersatz-Hammett novels about London PI Slim Callaghan, and during World War II he wrote a series of rather bleak espionage novels, all with “Dark†in their titles and lavishly praised by Anthony Boucher and others.

I don’t know if he’s worth rediscovering, but you can catch him as he looked in newsreel footage from 1946, dictating his then-latest thriller to a secretary, by going to www.petercheyney.co.uk and clicking first on “Links†and then on the image at the bottom of the screen.

The mail has just brought me the proof copy of my latest assault on the forests of America. Cornucopia of Crime is a 449-page gargantua bringing together chunks of my writing over the past 40-odd years on mystery fiction and some of my favorites among its perpetrators, from Gardner and Woolrich and Queen to Cleve F. Adams and Milton Propper and William Ard, not to mention screwballs like Michael Avallone and mad geniuses like Harry Stephen Keeler.

One small problem with this copy: on the title page the author’s name is conspicuous by its absence. This glitch will soon be corrected but I’m told that ten or twelve uncorrected copies are on the way to me by mail.

If they arrive before I leave for the Pulpfest in Columbus, Ohio late next week, I plan to bring them with me and — assuming there are a few collectors in attendance who are in the market for perhaps the most limited edition of any book on mystery fiction ever published! — sell them off. Consider this an exclusive offer to Mystery*File habitues.

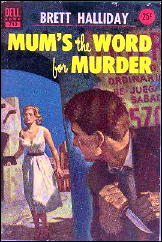

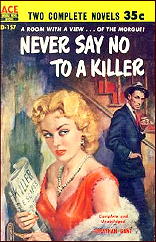

Editorial Comment. 07-22-10. Inspired by David Vineyard’s comments on Peter Cheyney’s contributions to the world of crime fiction, I checked out the website devoted to him that Mike mentioned. It’s definitely worth a look. I especially enjoyed the covers, a portion of one I’ve added below. Who could resist a book with a lady like this on the cover? Not me.

Artwork by John Pisani. For more, go here.