FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

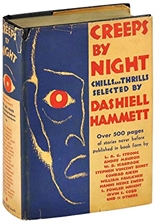

THE DEAD DON’T CARE (1938) made considerably more money for Latimer than his first three Crane novels, thanks to being bought by the high-paying Collier’s magazine and published as a 10-part serial (“A Queen’s Ransom,†14 December 1937 – 5 February 1938). Which perhaps explains why this fourth book in the series isn’t anywhere near so grotesque and bizarre as THE LADY IN THE MORGUE.

The setting is Florida, within driving distance of Miami and Key West, and we open with Crane and his sidekick Tom O’Malley approaching a resplendent mansion, their firm having been hired by the bank that serves as trustee of the fabulous Essex estate to investigate a series of “pay-$50,000-or-else†notes signed The Eye and delivered to playboy Penn Essex under impossible circumstances. Putting up at the family’s palatial shack, they find already in residence an assortment of characters, perhaps as in previous Crane novels a few too many, but nothing radical happens until Penn’s younger sister Camelia is kidnapped at gunpoint in front of a Miami gambling casino to which Penn is in hock for close to $25,000.

Thereafter the tenor of the notes from The Eye switches to “pay us fifty grand or we kill her.†Then the weirdest of the house guests, a woman who claims to be descended from a Mayan high priest, is poisoned in the middle of the night in her own locked bedroom with no one else inside except Crane, who’s sleeping off a sexual encounter with her. Our sleuth’s guzzling capacity is insatiable as usual but a few chapters before the end of the book he manages to supervise a traditional gathering-of-suspects at which by a sort of reasoning process he names the murderer.

But Camelia Essex remains in kidnapers’ hands, and the final chapters are devoted to a violent seaborne action sequence in which Crane takes part but is certainly no superhero.

Much of the narrative consists of simple declarative sentences as in Hammett but there’s also a fair amount of vividly colorful descriptive prose of the sort we never find either in Hammett or in earlier Latimer novels, starting with the first sentence: “Sunset splashed gold paint on the windows of the white marble house, brought out apricots and pinks and salmons in the flowering azaleas.†Early in Chapter XVI we find the following passage:

The clouds were splendid. They towered high above the horizon, giving the effect of a city on fire. Heliotrope smudged their bases, but the towerlike peaks were bright with scarlets, roses, salmons and oranges. Above, the sky was sapphire.

“Pretty gaudy,†Crane said. “It looks like Sam Goldwyn had a hand in it.â€

Even more unlike Hammett are the occasional wildly funny moments, like the one in Chapter III where Crane, several sheets to the wind, makes bold to correct O’Malley’s grammar.

“No. You do not use ‘trun.’ We are not going to be ‘trun’ to the alligators.â€

“You’re tellin’ me?â€

“If you have to use ‘trun,’ use it this way: he fell like a trun of bicks.â€

“You mean a trun of bricks.â€

“Or a one-trun tuck.â€

Less amusing is dat ole debbil n word, which crawls out of the woodwork once or twice in the final chapters.

The most memorable sequence in the book comes in Chapter XIII when Crane wakes up in the wee hours, in the mood for another round of amour, and begins sexually teasing the naked woman in bed next to him, then after a while discovers to his horror that she’s dead. A later scene takes place in Key West, where Ernest Hemingway famously had one of his homes, and in Crane’s company we visit Sloppy Joe’s, the bar where Papa hung out.

We never get to see the great author, of course, but from a conversation between Crane and some professional anglers we glean a few anecdotes about his fishing habits. One of the four kidnappers involved in the final action sequence happens to be known as Toad, which makes him the third crime-fiction character I’ve encountered — the others being Joseph P. Toad in Chandler’s THE LITTLE SISTER and Capitaine Crapaud in one of Gerald Kersh’s Karmesin stories — to sport the name of the sweetly singing little critter known to biologists as Bufo bufo.

Like the two Crane novels before it, THE DEAD DON’T CARE was adapted into a Crime Club series movie, but under a different title, THE LAST WARNING (1938), which was directed by Albert S. Rogell from a screenplay by Edmund Hartmann. Preston Foster and Frank Jenks were back as Crane and his sidekick Doc Williams who, as we’ve seen, had very little to do in the novel and was replaced by Crane’s other sidekick Tom O’Malley.

The names of the characters were de-exoticized: Imago Paraguay became Carla Rodriguez, Count Paul di Gregario was reduced to Paul Gomez, and the first names of the siblings Penn and Camelia Essex were toned down to John and Linda. I don’t recall ever having seen the movie but from the descriptions on the Web it seems to have followed at least the broad outlines of the novel, although I’d bet money that what I called the most memorable scene in the book, if filmed at all, was trun on the cutting-room floor.

***

The fifth and final Crane novel is quite different from the others. For one thing, we’re never told where the events take place except that it must be somewhere in the upper Midwest. For another, a good bit of the narrative is so bland it reads like stage directions. (A walks out by the front door. B enters by the French window.) I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that Latimer first planned the work as an original screenplay for the Crane movie series, then changed his mind or had it changed for him and reconfigured it as a novel. In any event RED GARDENIAS (1939) did well for him since it too first appeared as a serial in Collier’s (10 June – 5 August 1939).

If it were originally intended as a screenplay, clearly the primary influence on it was the first couple of sequels to THE THIN MAN (1934). Ann Fortune, Colonel Black’s niece, plays Nora to Crane’s Nick and engages in dialogue with him that’s sort of reminiscent of the exchanges between William Powell and Myrna Loy in those movies. A multi-millioned manufacturer of refrigerators and washing machines has retained the firm to investigate the suspicious death of his nephew, who was found dead of carbon monoxide poisoning in his sedan nine months earlier, with the scent of the titular gardenias on his clothing, and later the similar death of his son, who was likewise found dead of carbon monoxide poisoning in his garage about a month before the book opens.

Posing as a new hire in the manufacturer’s advertising department and with Ann in tow passing as his wife, Crane moves into the dead nephew’s house and, in the middle of his first night, surprises a burglar who turns out to be his client’s other son. Over the next few days he encounters other members of the family circle: the dead son’s widow, the dead nephew’s ex-wife, a second nephew who is a lawyer and represented the ex-wife in the divorce proceedings against his brother, a tennis-loving doctor who runs the local hospital, a gangster’s moll who was playing around with the dead nephew, the list goes on and on for perhaps, as in other Crane novels, a little too long.

Eventually there’s a third carbon monoxide poisoning in the family, followed by a suspenseful duck hunt, a shoot-out in an isolated farmhouse and, after perhaps too many complications, the exposure of a poorly concealed Least Likely Suspect. Among the plot problems is the fact that there’s never a scintilla of official suspicion about so many similar deaths in the same family, and you must pull down those raised eyebrows and stifle that giggle when you come to the ridiculous hospital action scene in Chapter 18.

In addition, you have to hold your nose when in Chapter 8 a black nightclub singer is gratuitously referred to (in the narrative, not by a racist character) as a jigaboo. Crane as usual guzzles up a storm, imbibing everything from Scotch and soda to champagne and laudanum. Between drinks he asks all sorts of questions about the murders and in general acts like anything but a newly hired advertising copywriter, yet no one ever suspects he’s not what he claims to be. The last line hints that he and Ann Fortune will soon get married, but if Latimer had any plans for other Nick-and-Nora-type books they came to nothing and Crane never appeared in print again.

***

It was the end for William Crane but not quite the end for Latimer’s involvement with the PI novel. In late 1940 or early ‘41 he made one final venture into the field, far from his best work but certainly the most controversial and therefore requiring a fair amount of space to discuss. For this reason the book known originally as SOLOMON’s VINEYARD and later as THE FIFTH GRAVE will be saved for next year. Happy holidays!