January 2007

Monthly Archive

Sun 7 Jan 2007

Quoting from the online edition of the Fresno Bee:

Albert Isaac “Buzz” Bezzerides, born in Ottoman Turkey to an Armenian mother and Greek father, grew up in Fresno in the same era as author William Saroyan. […] Mr. Bezzerides, who moved to Southern California as an adult, fell and suffered a broken hip late last year. He died New Year’s Day in a Los Angeles hospital. He was 98.

Here is his entry in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

BEZZERIDES, A(lbert) I(saac) (1908- )

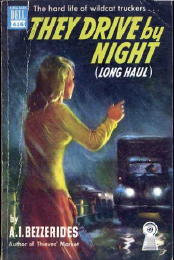

* * *Long Haul (Carrick, 1938, hc) Cape, 1938. Also published as:

They Drive by Night. Dell, 1950 and

Tough Guy. Lion, 1953. Film: Warner Bros., 1940, as

They Drive by Night; released in Britain as

The Road to Frisco (scw: Jerry Wald, Richard Macaulay; dir: Raoul Walsh).

* * _They Drive by Night (Dell, 1950, pb) See:

Long Haul (Carrick 1938).

* * *Thieves Market (Scribner, 1949, hc) [San Francisco, CA] University of California (U.K.) pb, 1997. Film: TCF, 1949, as

Thieves’ Highway (scw: A. I. Bezzerides; dir: Jules Dassin).

* * _Tough Guy (Lion, 1953, pb) See:

Long Haul (Carrick 1938).

Only two books, but influential ones. “Like Saroyan,” the obituary in the Bee goes on to say, “Mr. Bezzerides wrote novels influenced by his life in the San Joaquin Valley during the early part of the last century.” Due to what novelist Anthony Neil Smith on his blog Crimedog One calls their inherent “trucker noir” quality, their impact on the world of cinema has been even greater.

Among the other credits you can find for him at www.imdb.com is

Kiss Me Deadly , a 1955 masterpiece of film noir starring Ralph Meeker as Mickey Spillane’s favorite PI, Mike Hammer, filmed in (as they say) glorious black-and-white. Mr. Bezzerides wrote the screenplay.

First line: Mike Hammer: You almost wrecked my car! Well? Get in!

In another genre, Mr. Bezzerides was also the creator of The Big Valley, the Barbara Stanwyck TV western series that ran for 112 episodes between 1965 and 1969. His roots in the San Joaquin Valley, where the Barkley ranch was located, had a good deal to do with that success of that series as well.

[Thanks to Vince Keenan on his blog for the original tip on Mr. Bezzerides’ passing.]

Sun 7 Jan 2007

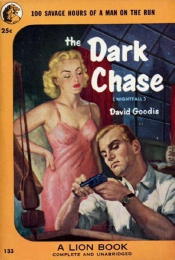

Today was the last day of GoodisCon 2007, and no, I wasn’t able to go, and whether there will be another, I have no idea. But here’s a question that occurs to me. What other mystery writer has had a convention dedicated to him and him alone?

I’ll qualify that by saying that Anthony Boucher is not an acceptable answer, as Bouchercons were always about more than Mr. Boucher. And as a brief aside, I suspect that many attendees of Bouchercons in recent years do not even know who Mr. Boucher was.

Searching on the Internet just now, I came across several sites relating to David Goodis that may be of interest, the first one of which may contain cover images of every edition of every book that Goodis wrote. (It does say “a selection,” so it’s more than likely that I’m exaggerating, but there are certainly quite a few for you to look at here, many of which I’ve never seen before. Not the one below, but many of the later editions and almost all of the foreign editions.)

You may have to follow the link at the bottom of the page that the link above leads you to. The first page that comes up contains a short biography of Goodis by Dave Moore. There are many other sites that I might send you to, but back in Crimesquad‘s archives I found another short biography and a review of Black Friday and Selected Stories (Serpent’s Tail, trade pb, July 2006).

It’s a book I missed when it came out. I’d put it on my birthday list, but then I’d have to wait another whole year. I’d rather not wait that long.

Contents:

Black Friday. Novel. Lion 224, pbo, 1954.

“The Dead Laugh Last.” Goodis writing as David Crewe.

10 Story Mystery Magazine, October 1942.

“Come to My Dying!” Goodis writing as Logan C. Claybourne.

10 Story Mystery Magazine, October 1942.

“The Case of the Laughing Ghost.” Goodis writing as Lance Kermit.

10 Story Mystery Magazine, October 1942.

“Caravan to Tarim.”

Collier’s, October 26, 1943.

“It’s a Wise Cadaver.”

New Detective, July 1946.

“The Time of Your Kill.” Goodis writing as David Crewe.

New Detective, November 1948.

I wonder what a copy of 10 Story Mystery Magazine for October 1942 goes for these days.

—

UPDATE: It didn’t take long for a report to appear online from someone who was there. Who better to give with some details than crime novelist Duane Swierczynski (pronounced “sweer-ZIN-ski”) on his blog, which you should be reading as a matter of course anyway…

Sat 6 Jan 2007

The book has not been published yet, at least not the revised edition. The manuscript was turned in sometime in middle of last year, but so far no date’s been set as to when it’s going to appear. When the Fourth Edition came out in 2003, the end date for the material covered was the year 2000. This is also when Al Hubin then began to look for someone to take over the task of editor and make sure that further editions would continue to appear. But when no takers were found, the decision was made that there would be no Fifth Edition.

Corrections and additions to the data in Crime Fiction IV continued to come in, however, and Al found himself unable to retire, as he’d planned, and the Revised Edition was the result. Rather than expand the bibliography chronologically, however, the cut-off date remained fixed at the year 2000.

Al was ready to retire again, but there was no end to the incoming flow of data, even with the closing date of 2000. He and I discussed this, and the upshot was he would continue to accumulate this addenda, but again only through 2000, and I would publish it on-line.

To that end, he has been sending me this addenda in parts, with eight such installments already on line at www.crimefictioniv.com. In his introduction to the addenda pages, Al fills in more of the details about the bibliography over the years, how it got started and how it grew.

As to my end, I’ve been taking advantage of the Internet, and as I go, I have been adding links and cover images not available in the printed editions. Links have been made to websites about the authors cited, and especially to www.imdb.com for every movie that Al has added as being based on a novel included in Crime Fiction IV.

Much of the Addenda included in parts 1 and 2 consists of connections to TV films, which had largely been neglected in early editions of CFIV. Using www.imdb.com, Leonard Mustazza’s The Literary Filmography and Alvin H. Marill’s Movies Made for Television as sources, many such TV movies have been identified and are now included.

Now in their enhanced form, and Internet-ready, as it were, Parts 1 and 2 have now been merged alphabetically in two sections, A through H and I through Z. I am now working on Part 3.

While the Addenda is hardly intended to replace the full Bibliography, my goal is also to have it stand on its own, as much as possible. To that end, I have been annotating some of the entries, especially when the authors are less well known. There is nothing I need to add to an entry of an author of the stature of Agatha Christie, for example. A link to one of the many websites about her should certainly suffice.

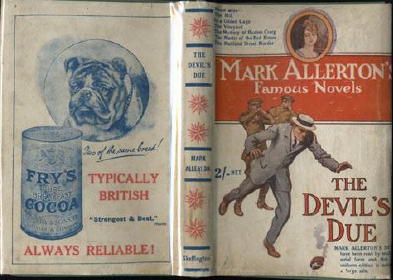

But for an author such as the following, the entry looks like this:

ALLERTON, MARK Pseudonym of William Ernest Cameron. As Allerton, the British author of ten works of crime fiction listed in the

(Revised) CFIV, five indicated as marginal. Listed in

The FictionMags Index are portions of three serialized novels from early American pulp magazines, only one of which is included in the (Revised) CFIV. The following are new entries.

The Devil’s Due. Skeffington, 1919

Her Hidden Husband. Thomson, 1927 [England]

-In a Gilded Cage. Skeffington, 1919

-The Master of Red House. Skeffington, 1919

If possible, every entry might look like this, but it’s not, and they don’t, not yet. But if you’re even only mildly interested in the bibliography of crime fiction, please feel free to stop by, browse around, and see what is there.

Fri 5 Jan 2007

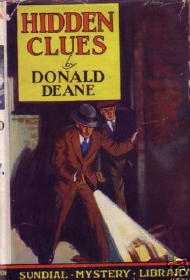

Jamie Sturgeon and I saw the same book listed on eBay around the same time, and each of us sent the information hidden in the listing to Al Hubin, author of Crime Fiction IV: A Bibliography (Revised), within a day of each other.

Jamie was one step ahead of me, however, and he’d already been in touch with the seller, who told Jamie how he’d gotten his information about the author of the book, Donald Deane, about whom nothing has been known until now.

It turns out that there never was a “Donald Deane,” and that the three books attributed to him in CFIV were actually written by Mary Fair, a rather progressive lady living in the Eskdale lake district of England, nestled at the foot of that country’s highest mountains.

Following the link from her name to the website devoted to her, you’ll find her life’s accomplishments described in considerable detail. I’ll quote only a summary that was printed in a newspaper about her, shortly after her death:

“Archaeologist, welfare-worker, explorer, geneaolgist, naturalist, photographer, writer and lecturer … this familiar and friendly figure, sometimes half-tramp, sometimes professorial, trudging up the fells in foul or fair weather to deliver orange juice or medicinal oil out of her knapsack to some infant arrival in a remote farmhouse; or, at midnight, popping up disturbingly from behind a beck-side drystone wall, where she had been recording the seasonal note of an unusual owl. … we shall miss more than her erudition: we shall miss her friendly, twinkling eye, her crisp opinions- sometimes inventively ornamented and not infrequently critical- but particularly we shall miss her humanity: her readiness to give a knowledgeable helping hand wherever it was needed.”

Of course it is her connection to the world of crime and detective fiction that is of interest. I’ll add another quote below, if I may. (Sorry. I said only one quote, but I was wrong.)

Oh, and by the way, she wrote detective novels, under the name Donald Deane. She never told anybody, but another of her friends, Whitehaven librarian Daniel Hay, solved the mystery. Published by John Hamilton of London, they were

The Fifth Tulip (1930);

The Luck of Luce (1931) and

Hidden Clues: A Lakeland story (1932). Most of the manuscript for a fourth novel, set in Scotland, also survives, written in cheap exercise books.

Here’s a cover scan of the third of these books, taken from the eBay listing that helped lead to this discovery:

Another entry, it almost goes without saying, if anyone’s keeping track, in the ongoing list of female mystery writers who kept their identities hidden by using initials in their byines or under the names of men.

Thu 4 Jan 2007

Posted by Steve under

InterviewsNo Comments

I might a little late in discovering this, but I just found an interview online with librarian Gary Warren Neibuhr, author of several landmark reference works in world of mystery fiction. It’s at Murderati and dated 12/29/07, but it can hardly be considered out of date.

Gary is the author of A Reader’s Guide to the Private Eye Novel (Reader’s Guides to Mystery Novels) (G. K. Hall, 1993) and Make Mine a Mystery: A Reader’s Guide to Mystery and Detective Fiction (Genreflecting Advisory Series) (Libraries Unlimited, 2003). I think both titles are probably self-explanatory, and if you don’t own them yourself, please make sure that you live close to a library that does. If they don’t, bug them until they do.

Gary’s most recent book is Read ‘Em Their Writes: A Handbook for Mystery and Crime Fiction Book Discussions (Libraries Unlimited, 2006). If the title doesn’t tell you exactly what the book’s about, it’s a self-help guide in helping you organize your own mystery discussion group, how to get participants, select titles, and so on. The interview concentrates most heavily on this, of course, but he talks about the other two books, too, as well as his own personal interests in mystery fiction. (Primarily private eye novels, it is not too surprising to learn: he has 6000 of them, he says, in his basement.)

One of the most popular articles that ever appeared on the original Mystery*File website was written by Gary about private eye Honey West, about whom if you know little, you should go read it, and right now.

Wed 3 Jan 2007

Posted by Steve under

ColumnsNo Comments

One of the highlights of the original Mystery*File website was the bi-monthly column of mystery this-and-that contributed by Mike Nevins. Just after the site went on hiatus, Mike sent me his comments intended for online publication in October 2006. The column has been languishing in my files ever since, and it’s time someone other than Mike and I read it. Here it is.

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

Mystery Commentary by Mike Nevins.

I am one of the six people in America who have never read a Stephen King novel. But at a recent library sale I picked up a copy of Danse Macabre (1981), the nonfiction book in which King celebrates the horror genre in the novels, stories, movies and TV series of his formative years. Turns out he defines horror very broadly to include what many of us would call suspense or noir – and includes among his favorite authors in that category several of my own. He particularly likes Psycho and several other Robert Bloch suspensers, describing them as “a powerful series of offbeat novels, which are only surpassed by the novels of Cornell Woolrich.” Much later in his book, while rhapsodizing over the novels of Ira Levin, he says: “The only other writer…who had that wonderful ability to totally ambush the reader was the late Cornell Woolrich … but Woolrich did not have Levin’s dry wit.” Whoever compiled the index for Danse Macabre missed both of these references to the Hitchcock of the written word (which are on pages 41 and 281 respectively) but caught a third (page 218), in which King praises the episode of TV’s anthology series Thriller based on the classic Woolrich story “Guillotine.” If I ever do an updated edition of First You Dream, Then You Die, I must remind the publisher to ask King for a blurb.

Hitchcock’s VERTIGO the inspiration for an episode of a TV Western show? Sounds impossible, but it demonstrably happened. “Incident at Alabaster Plain” (January 16, 1959) was the second broadcast episode of the classic Rawhide series starring Eric Fleming and Clint Eastwood. It’s a tad slow but has some good guest stars – Mark Richman, Martin Balsam and, I kid you not, Troy Donahue – and features a fine action climax as our stars shoot it out with killers who have taken over a frontier monastery. With his men wiped out, Richman as the psychotic gang leader runs up the stairs to the bell tower, pursued by Eastwood, and – well, you remember how Kim Novak wound up in VERTIGO. The first season of Rawhide is now available on DVD, and well worth buying too.

It’s well known that Hitchcock was an avid reader of crime and suspense fiction but would you believe that the foremost Soviet film-maker was too? According to Marie Seton’s Sergei M. Eisenstein: A Life (1952), the director of POTEMKIN, ALEXANDER NEVSKY and IVAN THE TERRIBLE collected Van Dine, Christie and other classic mystery novelists and filled the margins of his copies with extensive annotations in English, French, German and Russian. If we accept Seton’s account, Eisenstein studied the whodunit from the viewpoint of Christian mysticism, which in his last decades he believed in fervently, or at least fervently wished he could believe in. He equated the search for truth in detective fiction with the search for the Holy Grail in Christian legend, and took the position that the great detectives of fiction discover the truth by intuition rather than reason. Has anyone ever thought of collecting his notes on the genre as a book?

While I’m in a question-posing mood, here’s another. What world-famous mystery writer first created James Bond? Who wrote the story that begins: “With a serious effort James Bond bent his attention once more on the little yellow book in his hand. On its outside the book bore the simple but pleasing legend, ‘Do you want your salary increased by L300 per annum?’” No, 007 is not about to hit M for a raise and the author of these lines is not Ian Fleming, it’s Agatha Christie. Her Bond is a silly-ass young Brit with a hoity-toity fiancee and a stolen jewel on his hands, and “The Rajah’s Emerald” (first collected in England in The Listerdale Mystery, 1934, and over here in The Golden Ball, 1971) tells how he disposes of both.

Has anyone ever heard of an Ian Fleming spy novel called You Asked for It? It’s the Popular Library paperback edition of Casino Royale, published in 1955 when Fleming was all but unknown. “If he hadn’t been a tough operator, Jimmy Bond would never have risked” something or other, we are informed by the blurb on the back cover. “But it was toughness that had landed Jimmy his job with the Secret Service.” I suspect that the blurb alone makes this rare softcover worth a pretty penny more than the 8 1/3 cents I paid for it almost forty years ago in a secondhand store in upstate New York. I wish I had a few paperbacks whose blurbs extolled the toughness of other hardboiled ops

like Hank Merrivale, Al Campion and Herc Poirot!

Wanna hear about another strange paperback I picked up for pennies in my salad days? Murder Is Insane by Glenn M. Barns, a Jonathan Press digest-sized reprint of the 1956 hardcover edition, is clearly marked “Unabridged” on both the front cover and the inside title page. Buried amid the fine print of the copyright page, however, is the casually dropped news: “This book has been cut.” Small wonder I’ve never read the book.

Martin Scorsese’s THE DEPARTED, released a few weeks ago, strikes me as one of the most powerful films in the long career of arguably the finest living American director. On the off chance that someone who stumbles upon this column has read nothing about the movie, I should mention that it stars Leonardo Di Caprio as a young cop serving as a police mole inside Boston’s Irish mob and Matt Damon as Leo’s Academy classmate and the mob’s mole inside the force, the one spy reporting to top cop Martin Sheen and the other to gangster chief Jack Nicholson. It’s exceptionally violent and also exceptionally complex, with the climax so abrupt that I had to go on the Web to find out who fired the last shot that blew away the head of – but I’d be a toad if I said any more.

– Francis M. Nevins, October 2006

Tue 2 Jan 2007

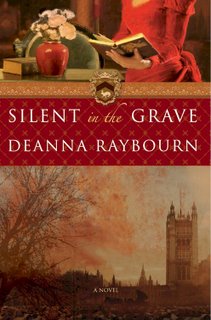

If you are interested in historical fiction as well as mysteries, you really ought to be reading my daughter Sarah Johnson’s blog readingthepast.blogspot.com.

And as I’m sure you’re well aware, once in a while, or even oftener than that, the two fields cross over. In today’s post she interviews Deanna Raybourn, whose first novel, Silent in the Grave, takes place in 1866 and is a PI novel as well, assuming that PI stands for “private enquiry agent” as much as it does the mean street variety of private eye that came along later.

Here’s Sarah’s description of the book:

Silent in the Grave begins a trilogy starring Lady Julia Grey, an unwitting and unlikely amateur detective. Her adventure begins in 1866. Her inattentive husband, Sir Edward Grey, has just collapsed and died during a dinner party at his London townhouse. The family doctor blames Edward’s longstanding heart condition, and Julia believes him, despite suggestions by Edward’s private inquiry agent, Nicholas Brisbane, that it was murder. It’s over a year later when Julia comes across compelling evidence that proves Brisbane was right. She engages Brisbane’s services, and during their investigation, she uncovers unpleasant and frequently sordid facts about her late husband’s behavior, as well as surprising truths about herself.

The interview that follows goes into both the historical aspects of the book and the writing of historical fiction in general. It’s well worth your time in reading.

Tue 2 Jan 2007

Taken from an email correspondence from Al Navis to Al Hubin, and the latter’s reply:

[In reference to the following entry in CFIV:]

DEMAREST, PHYLLIS GORDON (?-1973)

* * * The House on Washington Place (Curtis, 1974, pb) [New York City, NY; 1860s]

I have found the following book:

Demarest, Phyllis Gordon

** What Happened on the Melisande?, Cassell, London, 1971, FIRST EDITION, precedes the 1972 Curtis Books First American Edition, released posthumously.

On the rear flap it states that she died in 1969, but gives no birth year.

Hope this helps.

Al Navis

—

Thanks for the Demarest information. A little digging convinces me that she was an American, the daughter of novelist Samuel Gordon and stepdaughter of actor William Demarest, and that she was born 3/13/1908 and died 12/1969. So I’ll add the new book to the bibliography (via the permanent addenda at www.crimefictioniv.com) and also add/correct her dates.

Al

—

Steve again:

A quote, probably from the front cover of Melisande, describes it thusly: “Not since The Poseidon Adventure has there been as gripping a tale of terror at sea.” The House on Washington Place is a scarce book, with only one copy now being offered for sale on the Internet, nor is it clear that it is the Curtis edition. Her other novels appear to be either historical fiction about the early US, romances, or a combination thereof.

Except for a possible few, the short stories I’ve found for her appear to be romances. Most of these were found using the online FictionMags Index.

* Late One Night (sl) Smart Love Stories Feb 1937

* Dance for Your Love (ss) Love Book Magazine May 1937

* Stubborn Brat, Part One, Smart Love Stories, June 1937

* House of Hearts (nv) Love Book Magazine Sep 1937

* Just Forget Me (nv) Love Fiction Monthly Apr 1938

* Double Heartbreak (ss) Love Book Magazine Sep 1938

* Jig Saw (ss) Liberty Magazine Nov 19 1938

* If We Must Part! (ss) Ten-Story Love Nov 1938

* Hearts Don’t Break (ss) Love Book Magazine Apr 1939

* Yesterday’s Ecstasy (nv) Love Book Magazine Apr 1940

* Rendezvous with Love (nv) Love Novelettes Jun 1940

* Hangover from Childhood (ss) All-Story Love Dec 1 1940

* Love Under Fire (nv) Love Short Stories Jun 1941

* Second Chance at Love (ss) Love Book Magazine Jun 1941

* Galahad of Broadway (ss) Love Book Magazine Jul 1941

* [unknown title] Sweetheart Stories, Dec 1942

* Tonight is Ours (sl) All-Story Love Jan 1943

* Tomorrow Is Enough (nv) Love Book Magazine Jun 1943

* Love Asks No Questions (ss) Love Book Magazine Aug 1944

* One Love for Two (ss) Love Book Magazine Nov 1944

* Bride for a Hero (nv) Love Book Magazine Jan 1945

* [unknown title] Love Book Magazine, October 1945

* Jonnie Heartbreak (nv) 15 Love Stories Magazine Feb 1950

* Love Letter (ss) Love Book Magazine Sep 1953

* Meet Your Authors. Love Book Magazine Sep 1953 [short biographical piece]

—

From Victor Berch, a few last morsels of information:

About the only things I can add to Al’s note is some minutia. She came to the US with her father, Samuel, landing in NY on Dec. 10, 1913. By the 1920 Census, she was not living with her mother, Estelle, and stepfather (Carl) William Demarest. And the exact date of her death was December 22, 1969. Nothing in the LA Times regarding her death. Her mother’s maiden name was given as Colette, but I suspect that was a stage name, as she also was an actress, but probably a minor one.

UPDATE: Additional information uncovered by Victor on Phyllis Demarest’s background can be found here, on a later post.

Tue 2 Jan 2007

In my recent post on C. B. Dignam, I pointed out that it was not even known whether Dignam was male or female. Going on from there, I asked for a list of female mystery writers who hid their gender by using initials in their byline or by deliberately choosing a “male-sounding” pen name.

Commenting on that post, Bill Crider suggested Paul Kruger as a relatively recent example. On the Golden Age of Detection yahoo group, Nick Fuller posted the following:

E. X. Ferrars is the obvious one; she deliberately went for initials which sounded masculine. Then there’re E. C. R. Lorac, G. M. Mitchell (as the American publishers called the author of

Speedy Death), and P. D. James.

Several women authors also used male pseudonyms: Maxwell March (Margery Allingham), Anthony Gilbert (Lucy Malleson), Malcolm Torrie and Stephen Hockaby (Mitchell) and Gordon Daviot (Josephine Tey / Elizabeth Mackintosh). On the other hand, H. R. F. Keating used the ambiguous (and Christie-inspired?) pseudonym of Evelyn Hervey for his historical detective stories about a Victorian governess.

Thanks, Nick. I think you’ve come up with all that I’ve thought of myself, along with a couple more, although I cannot find anything to suggest that Speedy Death was ever published as by G. M. Mitchell. Can you confirm this?

Strangely enough, you failed to mention an author you discussed in an earlier posting on another subject — Guy Cullingford, pseudonym of Constance Lindsay Dowdy, according to one website.

This comes as a surprise to me. I did not know that Cullingford was female until now, or if I did, I’d forgotten it. In Crime Fiction IV, Al Hubin says that Cullingford was a pen name of C. Lindsay Taylor, which upon further investigation is a shortened version of (Alice) C(onstance) LINDSAY TAYLOR (1907-2000). Dowdy must have been her married name?

[UPDATE 01/03/07. Al Hubin did some investigatory work and discovered that Dowdy was her maiden name. See comment 3 below.]

In any case, she wrote one book as by C. Lindsay Taylor (Murder with Relish, Skeffington, 1948) and ten as by Cullingford between 1952 and 1991. Only five of them seem to have been published in the US.

The question I posed was of female mystery authors writing as men. I confess that vice-versa hadn’t occurred to me. There must be others besides Keating as Hervey, but other than cases involving male authors who wrote gothic romances under female names, as many did in the 1960s and 70s, this is a question I’ll have to think about some more.

—

The next posting on the same Yahoo group was from Jeffrey Marks, who confirmed exactly what I suspected. There’s a totally obvious candidate for inclusion that hadn’t even occurred to me:

Don’t forget Craig Rice, who actually used part of her real name ((Georgiana Ann Randolph Craig)), but then also used Michael Venning as well.

And assuredly there are more, but have we named all of the obvious ones so far? Probably not.

—

Getting back to C. B. Dignam briefly, who unknowingly brought this whole matter on, Google is *fast*. The day after my original post, I thought to double-check to see if there was anything on-line about him or her, and the only relevant blog or website that came up was … mine.

[UPDATE] 03-29-10. An email note from Sheila Mitchell, who was married to H. R. F. Keating, is both relevant and interesting. She says:

“This related to pseudonyms that women have used but you also instance that Harry wrote his Miss Unwin Victorian books under the ambiguous pseudonym of Evelyn Hervey and suggested that this may have some connection with Agatha Christie. Should you be interested it has no connection at all with Christie. He chose Hervey because that was a family name and Evelyn as you rightly say because of its ambiguity. Also interesting that publishers refuse to allow established authors their ambiguity and almost always reveal that of course this is so-and-so writing under the pseudonym X.”

Tue 2 Jan 2007

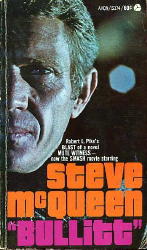

The following took place as a series of emails between Mark Sullivan and Jim Doherty which they recently posted on the rara-avis Yahoo group. They’ve graciously given me permission to reprint their conversation here. Thanks, gents!

Mark –

I recently read Robert L. Pike’s Mute Witness (actually it was a movie tie-in paperback retitled Bullitt). It had been several decades since I’d seen the movie and, to tell you the truth, all I really remembered was the car chase in and around San Francisco, so I came to the book relatively fresh.

I was a bit surprised to find that the book is set in New York and started wondering where the car chase was going to be. There wasn’t one. Instead I got a pretty tight police procedural that reads very fast, although the degree to which this previously, by all accounts, by-the-book cop broke the rules in this case was sometimes a bit suspect. All in all, though, a very satisfying read with a well-drawn main character.

So I watched the movie. It was interesting to see the changes that were made. First, the locale was shifted. Second, a major subplot was deleted, and the rules were stretched more than broken. Everything was stripped down (except for a young Jacqueline Bisset, alas, who played the added-in small role of the cop’s girlfriend). The book was very detailed about what was going on in the cop’s mind and investigation. The movie had long spaces with no words whatsoever, using just visuals. In other words, each played to its medium’s advantages, which rendered them equally satisfying.

One other thing: the movie changed a few names. Clancy became Bullitt, of course, I guess to make it harder, more catchy. The name change I found most interesting, though, was that of the two brothers in the “Organization.” In the book, they were Rossi. However, the movie drops the “i,” making the name less Italian (though the roles were still played by actors whose names and looks were Italian). And they changed one of the cop’s names from whitebread to Italian. I don’t remember Italian anti-defamation leagues starting until a few years later, with The Godfather movies. Were the studios already answering complaints about the stereotyping of Italians as mobsters in the ’60s? Man, they really lost that battle.

PS — As for the rumors that six hubcaps came off the Charger during the chase scene, I counted four (although two other bits go flying off the car that could be mistaken for hubcaps).

Jim —

The book was originally bought as a vehicle (no pun intended) for Spencer Tracy, who was going to play an NYPD squad commander in late middle-age named Clancy. In other words, he was going to play the character as written.

When Tracy died, it was decided to keep the bare bones of the plot, but change the lead character into the young, “hip” detective played by Steve McQueen.

Interestingly, Fish dropped the Clancy series after the success of Bullitt and started a new, San Francisco-set series of procedurals about an SFPD lieutenant named Reardon, which was also the the title of the first book in the series. Reardon was a young, handsome red-head given to wearing turtleneck sweaters and corduroy sportscoats. In other words, he was Bullitt with the name changed. Even more interestingly, that first novel about Reardon was expanded from a short story that had originally featured Clancy.

Actually the Anti-Defamation League started years earlier when The Untouchables was such a hit on TV. Something of a false alarm, really. In the first three episodes of the series, the main villains were, respectively, Jewish (Jake Guzik played by Nehemiah Persoff), Irish (“Bugs” Moran played by Lloyd Nolan), and southern poor white trash (“Ma” Barker played by Clair Trevor). Eliot Ness was an equal-opportunity gangbuster.

Mark —

Can I infer from this that Mute Witness was not the first novel to feature Clancy? Or were the earlier series entries short stories? And were they written as Fish or Pike — my movie tie-in copy of Bullitt creates on Pike on the cover and title page, but Fish on the copyright page.

Jim —

Mute Witness was, in fact, the first Clancy novel, but it was followed by The Quarry and Police Blotter, both of which appeared prior to Bullitt.

As near as I’ve been able to find out, Clancy made his debut in a 1961 short story called “Clancy and the Subway Jumper.” I’m pretty sure there were other Clancy short stories, including the one that was later expanded into Reardon, but I don’t recall the titles. I think the story that he expanded into the novel had “Eyes” or “Cat’s Eyes” in the title.

All the Clancy and Reardon entries were written as “Pike.” This was, apparently, a pun as a pike is a type of fish. He also wrote as A.C. Lamprey, a lamprey being another kind of fish.

The other Reardon novels, by the way, are The Gremlin’s Grandpa, Bank Job, and Deadline 2 A.M. The first book in the series acknowledged the technical assistance of SFPD’s then-police-chief, Tom Cahill, for whom the San Francisco Hall of Justice is now named, though, despite that high-powered assistance, he still managed to make a lot of errors.

—

Adapted from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

LT. CLANCY

* Author: Robert L. Pike

o Mute Witness. Doubleday, 1963 [New York City, NY]

o The Quarry. Doubleday, 1964 [New York City, NY]

o Police Blotter. Doubleday, 1965 [New York City, NY]

LT. JIM REARDON

* Author: Robert L. Pike

o Reardon. Doubleday, 1970 [San Francisco, CA]

o The Gremlin’s Grampa. Doubleday, 1972 [San Francisco, CA]

o Bank Job. Doubleday, 1974 [San Francisco, CA]

o Deadline 2 A.M. Doubleday, 1976 [San Francisco, CA]

« Previous Page — Next Page »