My survey of Turner did not indicate to me that he was a lost great. The Hume books seemed beat ’em up thrillers. The Turner and Brady books are more detection, with amateurs Amos Petrie and Ebenezer Buckle. It looks like Turner had his feet planted firmly in both schools of mystery fiction. I’ve read a couple of the Petries and Buckles, but the only one that stood out in any way for me was The Fair Murder, which had some quite exceptionally grotesque elements – it certainly is not cosy!

Curt

In my review and other commentary, I wondered about Turner’s death at the young age of 45. Victor Berch discovered his obituary in the NY Times [dated 02-06-45], but nothing in it referred to the cause of his passing. He had died the day earlier. I’ll quote briefly from the obituary anyway:

“Formerly a Fleet Street reporter, Mr. Turner left journalism to devote his time to writing thrillers, and while still in his early thirties was often called ‘the second Edgar Wallace.’ At one period he wrote a novel a fortnight.

“Frequently he spent weeks at a time living in London’s underworld to mix with criminals.

“A reviewer of [They Called Him Death, 1934/35] in The New York Times commented, ‘Swift action and plenty of it make this story a good example of the mystery-adventure type of thriller. If you prefer subtle deduction, you must look elsewhere.'”

I also wondered about Mick Cardby and whether his father should be also included as a series character in Allen J. Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV. Al replied:

Steve,

As for the Cardbys, Bill Lofts has this to say:

“The business of Cardby & Son, private detectives of Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, had been built up with the trust of both police and crooks. Whilst Mick Cardby was the younger and more prominent, Cardby senior had spent twenty years of distinguished service at Scotland Yard, reaching the rank of Chief Inspector.”

I owned 33 David Hume titles once upon a time, and I rather think I chose Cardby the younger because that’s the way the books were promoted … as Mick Cardby tales.

Altogether you’ve certainly convinced me that Mick Cardby, the son, is the principal player, with the father taking the lesser role. Mick Cardby books, they are!

Many thanks to Curt, Victor and Al for filling in some of the details on J. V. Turner, a/k/a David Hume. As usual, gents, it’s been a pleasure.

And by the not-so-insignificant way, I missed the quote from the Bill Lofts website the other day, and I shouldn’t have. And neither should you, if you are interested in mysteries published during the Golden Age of Detection and certainly no later than 1960.

Entitled The Crime Fighters, by W. O. G. Lofts and Derek Adley, it’s yet another project that Al Hubin is working on, putting online an alphabetical listing of many of the fictional characters found in all of those books, beginning with Pat & Jean Abbott (Frances Crane) and ending with Inspector Furneaux (Louis Tracy).

Um, yes. Unfortunately, only letters A through F are online and accounted for so far. It’s still worth your time visiting, and if you’re like me, you may stay a while.

From the Introduction:

This is essentially a bibliography of the following fictional characters:

* the private detective

* the private eye

* the official police investigator

* the amateur sleuth

* the adventurer type of detective, such as Bulldog Drummond and Norman Conquest, who were always on the side of law and order, as well as Robin Hood types like the Saint who were active on both sides

* the secret service agent of the Tiger Standish type, who nearly always worked with the Special Branch at Scotland Yard (but not those of the James Bond type, who were purely engaged in spying and espionage and rarely worked in collaboration with the police).

Thus, in general, we cover the fighters of evil-doers, but of course not including the American super-hero of the Superman type. The closest we come to this type is The Shadow and Doc Savage, who, while having certain mystic powers, are nonetheless ordinary men.

We have endeavoured in the main to include detectives and the like who have appeared in British publications, although we have found that most of those of any repute appearing in book form in this country have likewise appeared in the U.S., and of course the reverse is true.

“I’m seeking information on novelist Arthur Rees (Australian born 1872 (ish ), died 1942). Spent (perhaps much) time in England and wrote novels showing detailed knowledge of and interest in his adoptive home. His ‘detective/horror’ work includes The Shrieking Pit set in Norfolk and the tiny port of Blakeney.

“The book is prefaced by reference to Annie and Frances – my sisters in Australia, and a lengthy poem (of merit) about Blakeney.

“Any biographical information would be very much appreciated. Many thanks.”

—

As always, when asked about an author new to me, I turn first to Allen J. Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, wherein is found:

REES, ARTHUR J(ohn) (1872-1942)

*

The Hampstead Mystery [with John R. Watson] (n.) Lane 1916 [Crewe]

* The Mystery of the Downs [with John R. Watson] (n.) Lane 1918 [Crewe]

*

The Shrieking Pit (n.) Lane 1919 [David Colwyn]

*

The Hand in the Dark (n.) Lane 1920 [David Colwyn]

*

The Moon Rock (n.) Lane 1922

* Island of Destiny (n.) Lane 1923 [Insp. (Chief Insp.) Luckraft]

* Cup of Silence (n.) Lane 1924

* The Threshold of Fear (n.) Hutchinson 1925 [Colwin Grey]

* Simon of Hangletree (n.) Hutchinson 1926 [Colwin Grey; Insp. (Chief Insp.) Luckraft in a walk-on role].

* Greymarsh (n.) Jarrolds 1927 [Colwin Grey]

* The Pavilion by the Lake (n.) Lane 1930 [Insp. (Chief Insp.) Luckraft]

* The Brink (n.) Lane 1931

* Tragedy at Twelvetrees (n.) Lane 1931 [Insp. (Chief Insp.) Luckraft]

* Investigations of Colwyn Grey (co) Jarrolds 1932 [Colwin Grey]

• The Black Box • ss

• The Enamelled Chalice • ss

• The Finger of Death • nv, 1926

• The Grey Quill • ss

• The House by the Fells • ss

• The Katipo • ss

• The Lost Treasure of the Incas • ss

• The Missing Passenger’s Trunk • nv

• The Ten Commandments • ss

• The Valley of the Snakes • ss

* The River Mystery (n.) Jarrolds 1932 [Insp. (Chief Insp.) Luckraft]

* Aldringham’s Last Chance (n.) Lane 1933 [Insp. (Chief Insp.) Luckraft]

* Peak House (n.) Jarrolds 1933

* -The Flying Argosy (n.) Jarrolds 1934

* The Single Clue (n.) Robertson, Australia, 1940 [Insp. (Chief Insp.) Luckraft]

This listing includes the British editions only. A handful of the titles were published in the US, often with title changes; CFIV also lists one US title which has not yet been matched with an UK equivalent. Books in which a setting is indicated (most of them) take place in either England or Wales.

After consulting CFIV, as usual I sent out the usual cry for assistance, which was quick in arriving. From John Herrington came the bulk of the incoming information:

Hi Steve,

First it might be worth suggesting to R– that he contacts Local Studies Library in West Sussex, as Rees was living in Worthing in that county in the 1930s – may have died there?

From E. Morris Miller in Australian Literature (Rev 1950 ed).

“Arthur J. Rees was born in Melbourne in 1977 (typo I presume). He was for a short time on the staff of the Melbourne Age and later joined the staff of the New Zealand Herald. In his early twenties he went to England. His literary output belongs to the period that follows, and reflects little if anything of his Australian experience. He died in 1942. His proficiency as a writer of crime mystery stories is attested by Dorothy L. Sayers in the introduction to Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery and Horror (1928) and two of his stories were included in an American world-anthology, besides translations of other of his works into French and German.”

Not a lot, but at least a start.

His entry in 1935 Authors and Writers Who’s Who adds little, as well as giving his birth date as 1870! He is described as author and journalist, working for the London Times 1914-22 and editor of New Zealand Truth 1910-12. He is married, but no wife’s name given. And, of course, that he was living in Worthing at the time.

I wonder if he has an entry on AustLit. Allen has, or did have, access to this.

If you are interested, some of his books appear to be available as free e-books.

Then from Al Hubin:

Steve,

Sorry…no details other than birth/death dates in AustLit. But there is a note to a biographical sketch in “The Lone Hand” Volume 14 Number 84, April 1914, page 337. I’ve no idea where one might lay hands on this issue of this periodical, alas.

Heading back to do some Googling on my own, I came up with the following book descriptions from the Supernatural Fiction Data Base (which I did not know existed before):

The Shrieking Pit, 1919

Not, strictly speaking, a supernatural title. The locale that gives the book its title has a supernatural legend attached to it that is mentioned in passing, but there are no supernatural incidents in the story. (**)

The Threshold of Fear, 1925

A novel with borderline supernatural content: its villain has occult powers of mind control.

** As part of the introductory material for this book is the following: “As the scenes of this story are laid in a part of Norfolk which will be readily identified by many Norfolk people, it is perhaps well to state that all the personages are fictitious, and that the Norfolk police officials who appear in the book have no existence outside these pages. They and the other characters are drawn entirely from imagination.”

As John mentioned, four of Arthur Rees’s mysteries are available as free etexts. I’ve provided links to these in the entry from CFIV. If you (like me) dislike reading novels for entertainment from a computer screen, you can always download them as text files, then print them out. All it will cost you is the paper. And a new printer cartridge, I hasten to add, but still a bargain.

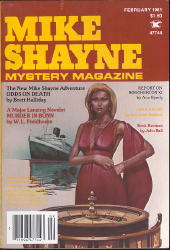

Prompted by a review by Ed Gorman of one of his early private eye stories for Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, author James Reasoner recently did some reminiscing on his own blog about the private eye characters he created back then, some 25 to 30 years ago.

There were four “Markham” stories, he says, calling Markham “sort of a dry run for my private eye character Cody, who appeared in the novel Texas Wind and several short stories of his own.”

James goes on to say that Markham “was the second private eye character I created for MSMM. The first was called Delaney … who appeared in a handful of short, very minor stories. Cody came along after Markham and I used both of them in stories for a while, but Cody last appeared in 1988, nearly twenty years ago.”

If you hadn’t missed it, yes, all three detectives have only a single name.

It’s a long post, and besides talking about his own characters, James also discusses the other authors who appeared in some of the same issues of MSMM as he did, writers such as Joe R. Lansdale, Edward D. Hoch, William L. Fieldhouse and others. Not only that, but he remembers the pair of editors who bought the stories as well: Sam Merwin, Jr., and Charles E. Fritch.

I’ll have to dig out some of the back issues of MSMM I have in my own collection. James also did many of the “Mike Shayne” short novels or novelettes that appeared in every issue during this same era, including the one pictured here.

It made the magazine one of the few places where you could be guaranteed being able to read a PI story anytime you picked one up. (The link above will take you to a list of many of the Mike Shayne stories that appeared in the magazine and who wrote them.)

James concludes by saying, “I’ve thought at times that a volume collecting all the Cody, Markham, and Delaney stories would make a nice little book. Maybe one of these days.”

If at all possible, make it sooner rather than later, James.

[UPDATE] 03-06-07. At the request of myself and a number of others, James has posted a complete list of all of his non- “Mike Shayne” private eye short fiction.

He goes on to talk about a few of the stories, including some additional details about his various PI characters. James concludes by saying:

“I believe that’s all of my private eye stories, eighteen in all. I would have guessed that there were more than that. Of course, if you include the novel Texas Wind and the 36 Mike Shayne stories I wrote, the total is a little more impressive. Sometime in the mid-Eighties I started a second Cody novel but didn’t get very far with it before setting it aside to do something else. I never got back to it and have no idea where the manuscript is now.”

[UPDATE] 09-08-08. It’s a little late to be considered breaking news, but a collection of 17 of James’s 18 private eye stories was published earlier this year by Ramble House. The title is For Old Times’ Sake, and you can order it here.

DAVID HUME – Requiem for Rogues

Collins, UK, hc, 1942. Reprints: 1946?, 1952. Collins White Circle #380, Canada, pb, 1949.

The author, first of all, is NOT David Hume (April 26, 1711 – August 25, 1776), who was a Scottish philosopher, economist, and historian, and according to at least one source, one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Nor is it his real name, for which see below. One does idly wonder why Mr. Turner chose it as a working by-line, though. It also makes it difficult to come up with information about him on Google, most of the searches picking up the wrong man, obviously.

On one website, I did come across the following, however:

In a jacket note in 1934, David Hume was described as having spent nine years in newspaper work, during which he was a frequent visitor to Scotland Yard. Apparantly, “in order to keep in touch with the criminal world,” Hume used to leave his home two or three times a year to live in the underworld. No doubt, this caused Howard Spring to say of Hume that “he shares Edgar Wallace’s practical knowledge of the techniques of crime.” Collins were happy to promote Hume as the “new Edgar Wallace.” His main series character was Mick Cardby.

From Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, which of course I turned to next, if not first, comes the following list of titles by Mr. Hume. These are the British editions only:

HUME, DAVID; pseudonym of J(ohn) V(ictor) Turner, (1900-1945); other pseudonym Nicholas Brady.

* Bullets Bite Deep (n.) Putnam 1932 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Crime Unlimited (n.) Collins 1933 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Murders Form Fours (n.) Putnam 1933 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Below the Belt (n.) Collins 1934 [Mick Cardby; England]

* They Called Him Death (n.) Collins 1934 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Too Dangerous to Live (n.) Collins 1934 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Call in the Yard (co) Collins 1935 [Det. Insp. Sanderson; England]

• Call in the Yard • na

The Thriller Mar 2 1935

• The Murder Trap • na

The Thriller Apr 13 1935

• The Secret of the Strong Room • na

The Thriller Dec 1 1934

* Dangerous Mr. Dell (n.) Collins 1935 [Mick Cardby; England]

* The Gaol Gates Are Open (n.) Collins 1935 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Bring ’Em Back Dead! (n.) Collins 1936 [Mick Cardby; France]

* The Crime Combine (co) Collins 1936 [Det. Insp. Sanderson; England]

• The Crime Combine • na

The Thriller May 2 1936

• Midnight’s Last Bow • na [unknown]

• The Murder Rap • na

The Thriller Jul 25 1936

* Meet the Dragon (n.) Collins 1936 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Cemetery First Stop! (n.) Collins 1937 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Halfway to Horror (n.) Collins 1937 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Corpses Never Argue (n.) Collins 1938 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Good-Bye to Life (n.) Collins 1938 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Death Before Honour (n.) Collins 1939 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Heads You Live (n.) Collins 1939 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Make Way for the Mourners (n.) Collins 1939 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Eternity, Here I Come! (n.) Collins 1940 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Five Aces (n.) Collins 1940 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Invitation to the Grave (n.) Collins 1940 [England]

* You’ll Catch Your Death (n.) Collins 1940 [Tony Carter; England]

* The Return of Mick Cardby (n.) Collins 1941 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Stand Up and Fight (n.) Collins 1941 [England]

* Destiny Is My Name (n.) Collins 1942 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Never Say Live! (n.) Collins 1942 [Tony Carter; England]

* Requiem for Rogues (n.) Collins 1942 [Tony Carter; England]

* Dishonour Among Thieves (n.) Collins 1943 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Get Out the Cuffs (n.) Collins 1943 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Mick Cardby Works Overtime (n.) Collins 1944 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Toast to a Corpse (n.) Collins 1944 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Come Back for the Body (n.) Collins 1945 [Mick Cardby; England]

* They Never Came Back (n.) Collins 1945 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Heading for a Wreath (n.) Collins 1946 [Mick Cardby; England]

TURNER, J(ohn) V(ictor)

* Death Must Have Laughed (n.) London: Putnam 1932 [Amos Petrie; England]

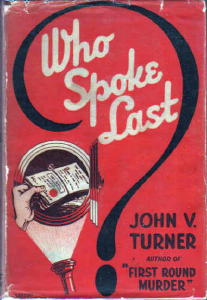

* Who Spoke Last? (n.) London: Putnam 1932 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Amos Petrie’s Puzzle (n.) Bles 1933 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Murder-Nine and Out (n.) Bles 1934 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Death Joins the Party (n.) Bles 1935 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Homicide Haven (n.) Collins 1935 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Below the Clock (n.) Collins 1936 [Amos Petrie; London]

BRADY, NICHOLAS

* The House of Strange Guests (n.) Bles 1932 [Rev. Ebenezer Buckle; London]

* The Fair Murder (n.) Bles 1933 [Rev. Ebenezer Buckle; England]

* Week-End Murder (n.) Bles 1933 [England]

* Ebenezer Investigates (n.) Bles 1934 [Rev. Ebenezer Buckle; England]

* Coupons for Death (n.) Hale 1944 [England]

I don’t know about you but these are all new names to me, both that of the author (and his pen names) and his characters. Back to Google, it seems. Here’s a snippet of a review from The Bookman, 1933, of the US Holt edition of Nicolas Brady’s The House of Strange Guests:

“Murder in an English country house, the headquarters of a blackmailing gang. Expert detective work by the erratic Reverend Ebenezer Buckle who, tired of saving souls, tries his(?) …”

Another snippet of a review, this one from The Librarian and Book World, date?, of Brady’s The Fair Murder:

“This is another detective story [in] which the Rev. Ebenezer Buckle unravels [a] mystery. But what a mystery! What [a] story! It is as gruesome and horrible … ”

Seeing a few shorter works of fiction collected under David Hume’s byline, I checked out the online Fictionmags Index, with the following results. [* = included in CFIV list above, either as a novel serialized earlier in magazine form, or as a story collected later in book form]

HUME, DAVID; pseudonym of J. V. Turner, (1900-1945)

* The Secret of the Strong Room (na)

The Thriller Dec 1 1934 [Det. Insp. Sanderson]

* Call in the Yard (na)

The Thriller Mar 2 1935 [Det. Insp. Sanderson]

* The Murder Trap (na)

The Thriller Apr 13 1935 [Det. Insp. Sanderson]

A Basin of Trouble (ss)

The Thriller Jun 29 1935

The Crook’s Day Off (ss)

The Thriller Aug 31 1935

He Was Pinched for Nothing (ss)

The Thriller Oct 19 1935

* Meet the Dragon (sl)

Detective Weekly Jan 4, Jan 11, Jan 18, Jan 25, Feb 1, Feb 8, Feb 15, Feb 22, Feb 29, Mar 7 1936 [Mick Cardby]

Anything to Say (ss)

The Thriller Feb 15 1936

The Wrong Bottle (ss)

The Thriller Mar 7 1936

Times Were Bad (ss)

The Thriller Mar 28 1936

* The Crime Combine (na)

The Thriller May 2 1936 [Det. Insp. Sanderson]

* The Murder Rap (na)

The Thriller Jul 25 1936 [Det. Insp. Sanderson]

Who is Midnight? (na)

The Thriller Sep 5 1936

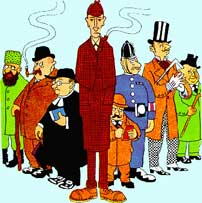

More googling, this time on Hume’s detective Mick Cardy. At this point I still knew nothing about him. On a website devoted to Inspector Maigret I discovered the following piece of art:

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8.

Maigret is the second gentleman on the left. Although they don’t have the original art, this cartoon came from the Storm-P museum in Copenhagen, and the curator, Jens Bing, identifies it as first appearing on the cover of the Danish pulp crime magazine Stjernehæftet in 1946. Bing sent a a copy to the Danish branch of the Sherlock Holmes Society, and here are the results they came up with for the others in the scene:

1. Dostoevski’s Porfiry, from

Crime and Punishment

2. Maigret

3. G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown

4. Sherlock Holmes

5. Agatha Christie’s Poirot

6. David Hume’s Inspector Cardby

7. Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin

8. H.C. Bailey’s Reggie Fortune (?)

I don’t think I would gotten many of those, assuming that these are the right answers. How would you have done? But no matter, it would seem that Mick Cardby was actually Inspector Cardby, but this is not so, as we shall see in a minute. I didn’t include them in the CFIV listings, but two of Hume’s books were indicated as being the sources of films based upon them. So off I went to www.imdb.com, where I found the following useful information:

Plot summary for The Patient Vanishes (1941) aka They Called Him Death [The latter being the title of a 1934 book by Hume.]

James Mason as a private detective [Mark Cardby], whose father is a Scotland Yard man [Gordon Maclead as Inspector Cardby], takes a case involving extortion and kidnapping. A young girl is kidnapped from a nursing home and he advises the girl’s father not to pay the ransom. After several near-misses on his life, he learns that the doctor in charge of the nursing home has been taken prisoner by the kidnappers. And then the wicket gets stiff or stuffy, or whatever wickets do.

Aha. Mick Cardby is a PI, not a gent from the Yard at all. We’ve learned something. (And you who knew already can stop the knowing looks at each other.) One more movie from the IMDB:

Too Dangerous to Live (1939) aka Crime Unlimited. [The latter being the David Hume title from 1933.] With Edward Lexy as Inspector Cardby, but no Mick Cardy listed in the credits, and no synopsis of the story.

But from the All Movie Guide comes the following Plot Description:

It took two directors to bring this modest British thriller to the screen. The story concerns a gang of international jewel thieves, headed by a “mystery man” who is never seen and who communicates with his minions through a microphone. Rival criminal Jacques LeClerq (Sebastian Shaw) gains the gang’s confidence, joining them on their biggest caper. Only when it’s too late to back out does LeClerq reveal that he’s actually a member of the French police. Without revealing the identity of the criminal mastermind, it’s worth noting that one of the actors plays a dual role, a fact spelled out in the opening credits.

And from BFI, apparently there is a PI involved, after all:

A private detective wins the confidence of a gang he is after, but has to rob a woman whose niece he finds attractive. The leader turns out to be an old friend and he fights his way from a burning garage.

I am sure that if you were to find a copy to watch, all of this confusion may be very easily straightened out. But a question remains: Who was the more important of the two characters, Inspector Cardby or his son Mick? Should both of them be included in CFIV as significant Series Characters?

And as you can easily see, Hume under his many aliases was extremely prolific. I’m sure you thought the same thing when you read through that list of mysteries up above. Could anyone who wrote so many detective novels so quickly be any good at it? Hold that thought. We’ll get back to it in a minute.

Hume also died young, at only 45. Could war injuries have had anything to do with his death? Having no answers, only these questions and more, unless you can enlighten me, I’ll move on to the major business at hand, which is a review of Requiem for Rogues.

In which the leading character in is neither Cardy, father or son, but rather Tony Carter, a wisecracking crime reporter who appeared in three of Hume’s adventures, of which this is the third. He’s rather full of himself as well, as one might put it. Here’s a piece of a conversation that takes place on page 22 between Carter and his immediate superior at the Echo:

Cartwright pressed his fingers together, stared at the ceiling. Carter also looked up. He wondered if his reprimand was written on the plaster. He sighed slightly as he waited for the attack to commence.

“To commence,” announced Cartwright, your methods are so unconventional that one day you will land this paper into most serious trouble. So far the luck has been with you. That cannot last for much longer. Then you’ll be in jail, and the

Echo

will be faced with a heavy libel action. In the future follow a more conservative line of conduct, be more orthodox. See?”

“Surely. You don’t want any more exclusive stories. The paper really wants the official news handed out in the Press room at the Yard – and nothing else. If that is so you’re wasting your money, and my time. Get a fourteen-year-old office boy, pay him ten shillings a week, let make the Yard call three or four times a day. And he’ll be a howling success.”

Cartwright wriggled. This interview was not what he had anticipated – not by a long, long way.

Suffice it say that Carter convinces Cartwright to give him a free hand in this case of the drive-by killing of one Percival East, dead by means of a bullet between the eyes on page eight, and right before the eyes of a later berated Detective Spriggs.

By page 69, the police are confused enough – and well they should be – to give Carter a free hand as well, as the case is seemingly awash with far too many clues and then again, far too few. But the more Carter digs into the case, the more deeply Percival East is discovered to have roots in the world of crime: the rackets, blackmail, the works.

Incidentally, totally relevant to nothing, I don’t know why everyone in this book refers to members of the police force as “splits.” It’s a new one on me, but the rest of the slang I managed to decipher with no particular difficulty. Conversations, though, which should have taken a page at the most to start and end invariably took four or five, which means that Hume was either a master of dialogue or he needed these long dialogues to fill the novel to a proper length. As for myself, I will not say padding, as I found these conversations to be rather imaginative, at the least.

There is no detection in this mystery novel, per se. Carter runs around London a lot, meets with his crew of regular informers a lot, and in so doing irritates the killer a lot, and enough so to make him (or her) make moves and counterattacks he (or she) really shouldn’t have done. If Carter had only been left alone, one might think, the case would never have been solved. One might very easily be right.

This probably also answers the question I asked up above but didn’t answer until now.

— January 2007

HAVING WONDERFUL CRIME. RKO, 1945. Patrick O’Brien, George Murphy, Carole Landis, George Zucco. Co-screenwriter: Stewart Sterling; directed by A. Edward Sutherland.

Based on the novel of the same name by Craig Rice, which I haven’t read, but all the sources which I have read say that the movie is nothing at all like the book. Murphy and Landis play the newly wed Jake and Helene Justus, while O’Brien is their long-suffering buddy in crime-solving, lawyer Michael J. Malone. (It was John J. Malone in the books. That much I do know.)

The story has something to do with a magician who disappears in the middle of his stage act, then reappears in a trunk brought to a lakeside resort by his female assistant – or does he? In spite of the trio’s suspicions, he’s not in the trunk, but not to worry – he eventually turns up dead and there really is a case to be solved.

I couldn’t tell you one way or another if the plot (the motive and where the body is when) makes any sense, and truthfully I don’t think that anyone involved in this madcap sort of affair, near slapstick at times, really cared.

Pat O’Brien doesn’t nearly match the image of Malone I have in my head – for some reason, I see him as a shorter, more somber sort of fellow – but George Murphy is right on as Jake Justus, and Carole Landis is even more perfect as Helene. Her beautiful, smiling face, her lithesome figure and (as Helene) her slightly scatterbrained approach to life and solving murder mysteries, makes me wonder why her career in the movies never went any further than it did. (Due to illness, among other factors, she committed suicide only three years after this movie was released.)

Even though from a murder mystery point of view there is much to be desired from this particular film, the performances of the three main characters make this a must-see, especially to watch Miss Landis in such high form, high spirits and in high fashion.

THE GREAT FLAMARION. Republic, 1945. Erich von Stroheim, Mary Beth Hughes, Dan Duryea, Stephen Barclay. Directed by Anthony Mann.

A curiously flat film noir with oft-time director Erich von Stroheim as Flamarian, a vaudevillian headliner who falls for the wiles of femme fatale Mary Beth Hughes, an assistant in his pistol markmanship act. Her husband, Dan Duryea, is the other assistant in the act, a man driven to jealousy and as a consequence, given heavily to drink.

Flamarion is a stolid, impassive, lonely man, once thrown over in love by a double-crossing woman, who’s vowed to never allow it to happen again. Contemptuous, however, of the weakness he sees in Al Wallace and tempted by the flirtatious Connie Wallace, he at length lets his guard down, to his own disaster – and as it happens, to the others in this ill-fated triangle.

The long scene during which Flamarion waits for Connie in a hotel bridal suite in buoyant anticipation, only to realize the inevitable, is as painful to watch as anything I’ve seen in a film in some time. Duryea is perfectly cast in his role, slickly conniving yet weak-kneed and a somewhat pitiful excuse for a man – a fact that the viewer is quickly made aware of. It’s a part made just for him.

I don’t believe I’ve seen Mary Beth Hughes in a movie before, although she was around throughout the 1940s in B-movies like this, though often in uncredited performances. Her body language in the role was as crucial as her spoken dialogue, and she made the best of both.

But the reason I called the film flat? The main story is presented in the form of a long, uncomplicated flashback. When you know the fate of two of the characters from the beginning, and you can soon guess that of the third, it’s just about impossible for any movie or any director or any cast to generate a feeling of suspense, and The Great Flamarion is no exception.

On the other hand, if it had been filmed linearly, which would have been the only alternative, there simply aren’t enough twists and turns in the plot for the otherwise lightweight tale to have gone anywhere at all. Mann made the best of two choices, in my opinion, but in spite of some more better than average performances from the players, the movie didn’t ring any bells for me.

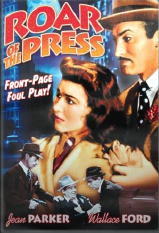

ROAR OF THE PRESS. Monogram, 1941. Wallace Ford, Jean Parker, Jed Prouty, Paul Fix. Directed by Phil Rosen.

What this Grade B murder mystery movie is more than it is a murder mystery is a comedy about crime beat newspapermen and their wives who never see them. Wallace Ford is the reporter (Wally Williams) who spots a body falling from the top of a Manhattan skyscraper on the day and his bride of one day come to the city to spend a few days honeymooning. Jean Parker, of Detective Kitty O’Day fame (in certain circles), is his bride Alice, who hails from a small town in New England and who quickly joins the club – that of the long-suffering wives of the other reporters on her husband’s newspaper.

Dead is the head of a pacifist league, in case it matters, and it doesn’t much, which turns out to be a front for fifth columnists and saboteurs. When Wally finds yet another body before the cops do, the cops get sore, and rightfully so, as all of the clues are in the pockets of Wally. Jed Prouty plays Wally’s editor, who cleverly keeps him on the case, even with the lure of a dinner of corned beef and cabbage waiting for him at home. One would think that the slim and decidedly pretty Mrs. Williams would be lure enough, but not so.

Paul Fix is the head of a numbers racket with a heart of gold, and thereby saves the bacon of both Mr. and Mrs. Williams when the gang of bad guys start to get overly worried about what Wally knows, which truthfully is very little, even with the clues he obtained before the police did.

As for director Phil Rosen, who later directed a number of Charlie Chan films, he makes the best of also truthfully very little, and the result is surprisingly entertaining.