I refrained from posting this yesterday, in case it would be considered a particularly cruel April Fool’s joke if we were wrong. I also waited until we had obtained as much information as we could about what we have discovered, we being Al Hubin, Marv Lachman, Victor Berch and myself.

First came an email from Al:

Although I don’t recall any word about Donald Hamilton’s passing, it certainly appears that he has. Contemporary Authors gives his birth date as 3/24/1916, and there’s a Donald B. Hamilton in the Social Security death benefit records with this birth date who died 11/20/2006 in Ipswich, MA.

From Marv Lachman:

I think I can confirm that it was THE Donald (Bengtsson) Hamilton who died. He formerly lived in Santa Fe and was listed in our phone book as Donald B. Hamilton, though no street address was given. I checked our phone book today and there is [only] a Donald R. Hamilton, with a street address. I then spoke to someone at the library who knew him, and she says that he moved “back east.” That would account for his death in Ipswich, Mass.

From Victor Berch:

There was no obituary for Donald Hamilton in the Boston papers. There was even no death notice. This can happen since someone has to pay in order for a death notice to be inserted in the newspapers. If Hamilton was in a nursing home at the time or a hospital, neither institution would pay for such a notice.

At any rate, I did find some information about Donald Hamilton. He was born in Upsala, Sweden. Came to the US aboard the SS Droltingholm on the 6th of October in 1924. He was the son of Bengt and Elise Hamilton. His father was a doctor and at that particular time was associated with the Childrens’ Hospital in Boston. He was also a professor at Harvard (probably Harvard Medical School). By 1930, the family had moved to Baltimore, MD.

That’s about all I could dig up on his early years.

From Al Hubin:

I think it must be “our” Donald Hamilton, though it is surprising his passing went unnoticed for so long.

So here is where we stand. You now know as much as we do. Obviously there are many questions as yet unanswered. Victor also suggested getting the death certificate of the Donald Hamilton who died, but at this point in time we have not done so.

For a long retrospective look by John Fraser into the mystery and espionage fiction of Donald B. Hamilton, best known as the creator of secret agent Matt Helm, go to https://mysteryfile.com/Hamilton/Hamilton.html.

Highly recommended also is a followup piece that Doug Bassett did for Mystery*File, a nicely done in-depth comparison of Matt Helm with Travis McGee, the colorful series character created by John D. MacDonald.

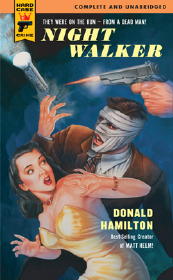

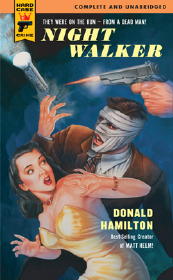

Cover art by Tim Gabor.

[UPDATE] Early this afternoon Charles Ardai confirmed the death of Donald Hamilton. Charles is the man behind Hard Case Crime, who reprinted Hamilton’s Night Walker in January 2006. […] Charles has now left a comment to this effect. In a separate email to me he added, “We are very proud to have worked with Don and to have published one of his books. He was one of the giants, and he’ll be missed.”

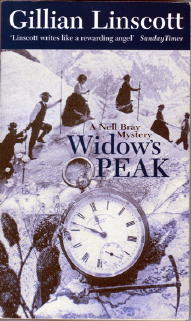

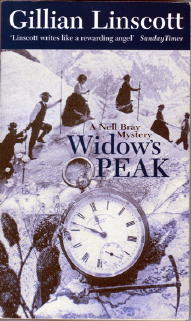

GILLIAN LINSCOTT – Widow’s Peak

Warner Futura, UK, pb. Hardcover editions: Little Brown, UK, 1994; St. Martin’s Press, US, 1995, as An Easy Day for a Lady.

Over her career Gillian Linscott’s sizable list of mystery fiction has featured two different series characters. Nell Bray, who is in this one, first appeared in print in Sister Beneath the Sheet, which was published in 1991. Timewise, that book took place in 1909, or very early on in her life as a militant London-based suffragette. Her adventures have appeared more or less chronologically ever since, except for the last two, at least one of which has jumped back in time to her earlier, more formative years.

In Linscott’s first four books, the detective of record was Birdie Linnet, a divorced former policeman trying to maintain contact with his daughter. Not having read any of them, I know little more than that. Nor I have come across any reason why Linscott abandoned him as a character, though the most likely one, of course, is that it happened at the publisher’s wishes, not hers. There are also three non-series books in her bibliography, which I’ve expanded below from the one found in Allen J. Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV:

British editions only:

# A Healthy Body (n.) Macmillan 1984 [Birdie Linnet; France]

# Murder Makes Tracks (n.) Macmillan 1985 [Birdie Linnet; Italy]

# Knightfall (n.) Macmillan 1986 [Birdie Linnet; England]

# A Whiff of Sulphur (n.) Macmillan 1987 [Birdie Linnet; Caribbean]

# Unknown Hand (n.) Macmillan 1988 [Oxford]

# Murder, I Presume (n.) Macmillan 1990 [London; 1874]

# Sister Beneath the Sheet (n.) Scribner 1991 [Nell Bray; France; 1909]

# Hanging on the Wire (n.) Scribner 1992 [Nell Bray; Wales; Hospital; 1917]

# Stage Fright (n.) Little 1993 [Nell Bray; London; 1909]

# Widow’s Peak (n.) Little 1994 [Nell Bray; France; 1910]

# Crown Witness (n.) Little 1995 [Nell Bray; London; 1910]

# Dead Man’s Music (n.) Little 1996 [Nell Bray; England; 1910 ca.]

# Dance on Blood (n.) Virago 1998 [Nell Bray; London; 1912]

# Absent Friends (n.) Virago 1999 [Nell Bray; England; 1918]

# The Perfect Daughter (n.) Virago 2000 [Nell Bray; England; 1914]

# Dead Man Riding (n.) Virago 2002 [Nell Bray; England; 1900]

# The Garden (n.) Allison & Busby 2003

# Blood on the Wood (n.) Virago 2003 [Nell Bray; England; early 20th century]

Many of these have been published in the US by St. Martin’s, so Linscott is far from an unknown author on this side of the Atlantic. On the other hand, none of them have been published over here in a mass market paperback edition, so I could easily be wrong about how recognizable her byline might really be.

There are several websites devoted to her and her fiction, but none of them seems to answer the question whether or not she is still writing. If you know more, you might pass the word along to me.

The primary factor in knowing Nell Bray as a character is her passionate devotion to the Right of Women to Vote, ironically making the one book of hers that I have happened to read, Widow’s Peak, perhaps the least typical in the series. Nell is on vacation in France from her brick-throwing proclivities in this one – in Chamonix, to be exact, at the foot of Mont Blanc, where very early on in the book a dead man is found in the ice, having known to have been killed in an “accident” which occurred thirty years earlier. The only early feminist items on the agenda are subtle, and they appear only in context, but (strangely enough) they manage to be all the more noticeable when they do.

You will, of course, have noticed that I placed the word “accident” in quotes. Any self-respecting mystery reader will know immediately that there no accident is involved, and there never had been. Nell, who is also a skilled translator by profession, is hired by the dead man’s brother and his family to help facilitate their taking the dead man’s body back to England. This gives her an immediate, insider’s view of their various activities – which I’ve deliberately phrased this way, since for a good portion of the book, there is no investigation into a murder, per se.

But the dead man’s journal, found in the ice near his body, contains several entries with sobering implications, and soon enough Nell finds herself in the thick of things, as seems to be the usual case for her. As a historical novel, Widow’s Peak is quite delightful, picturing as it does the Bohemian way of life in the village in some detail, not to mention (if you take a good look at the cover) sharp images of pre-war hiking expeditions up the mountain. Both men and women were in these co-educational parties, as if they were on larks of some magnitude, which indeed they were.

While keeping me up far past my bedtime, the detective story unfortunately concludes in more post-Victorian melodrama than I’d have preferred. The twists and turns of the plot along the way, however – some foreseeable, others thankfully not – certainly made up for it in spades (and ropes and axes and all other shapes and forms of primitive mountaineering equipment).

PostScript: For an excellent overview of other mysteries taking place in the days of women’s rights movements, check out this recent post in Elizabeth Foxwell’s blog, The Bunburyist.