July 2007

Monthly Archive

Tue 17 Jul 2007

Posted by Steve under

Authors ,

AwardsNo Comments

DANIEL JUDSON – The Darkest Place. Nominated for Best Private Eye Hardcover Novel of the Year, 2007.

St. Martin’s, hardcover, May 2006. Paperback reprint: May 2007.

Book Description:

The cold of winter has come to the far reaches of Long Island, New York. The summer people are gone. So is the sunshine. And in the dark, a man carries a body to the water’s edge. It’s not his first – and he’s not done yet…

The police are talking about suicides. But a handful of people suspect something darker is going on. One is a college teacher drowning himself in booze and dangerous sex. One is a former high school football star who wants a second chance. And between them is a mysterious private investigator [Reggie Clay] who believes that a beautiful, amoral young woman is connected to the killings.

Soon, things will spin out of control. Clues will point in all the wrong directions. Then, it will be up to a few lost souls – men and women who know all about monsters – to bring a killer into the light….

About the Author:

Daniel Judson is the Shamus Award–winning author of two previous novels, The Bone Orchard and The Poisoned Rose. He lives in Connecticut, where he writes full-time. He is a graduate of Southhampton College, and his time spent living in the Hamptons (particularly the parts you don’t find in the society pages) was the inspiration for the setting and characters in The Darkest Place.

Review Excerpts:

Publishers Weekly: “Judson does a terrific job of setting up a complex plot that’s full of surprises, even if the pieces fit together a bit too conveniently in spots.”

Booklist: “Told from multiple points of view, populated with well-drawn moral and amoral characters, and permeated with violence, this riveting albeit bleak crime novel offers a strong sense of place along with thoughtful rumination about doing the right thing and finding redemption for past actions.”

This is the first Reggie Clay novel. Judson’s previous two books featured PI Declan “Mac” MacManus:

The Bone Orchard, as by D. Daniel Judson. Bantam, paperback, March 2002.

The Poisoned Rose, as by D. Daniel Judson. Bantam, paperback, October 2002.

Mon 16 Jul 2007

PAULA GOSLING – Death and Shadows

Warner, British paperback; 1st printing, 2000. British hardcover edition: Little, Brown; 1998. No US edition.

A brief bit of biographical information first, if you’ll allow me, because an explanation’s going to be needed as to why a book taking place in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula has been published in the UK but never here in the US. According to one website, Paula Gosling was born in Detroit in 1939, but she moved permanently to England in 1964. After working as a copywriter and a copy consultant she became a full-time writer in 1979.

Taken from both that website and Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, here’s a complete list of her book-length mystery fiction, as published in the UK. Most of these are also available in paperback editions, but I haven’t taken the time to investigate into these. The last four, though – the ones marked # – have never had a US edition:

• A Running Duck (n.) Macmillan 1978 [San Francisco, CA]

= Fair Game (n.) Coward 1978. Revised and expanded from:

A Running Duck.

• The Zero Trap (n.) Macmillan 1979 [Arctic]

• Loser’s Blues (n.) Macmillan 1980 [London]

= Solo Blues (n.) Coward 1981. See:

Loser’s Blues.

• The Woman in Red (n.) Macmillan 1983 [Spain]

• Monkey Puzzle (n.) Macmillan 1985 [Lt. Jack Stryker; Ohio; Academia]

• The Wychford Murder (n.) Macmillan 1986 [Luke Abbott; England]

= The Wychford Murders (n.) Doubleday 1986. See:

The Wychford Murder.

• Hoodwink (n.) Macmillan 1988 [Lt. Jack Stryker (only briefly); Ohio]

• Backlash (n.) Macmillan 1989 [Lt. Jack Stryker; Michigan]

• Death Penalties (n.) Scribner 1991 [Luke Abbott; London]

• The Body in Blackwater Bay (n.) Little 1992 [Lt. Jack Stryker; Matt Gabriel; Michigan]

• A Few Dying Words (n.) Little 1993 [Matt Gabriel; Michigan]

• The Dead of Winter (n.) Little 1995 [Matt Gabriel; Michigan]

• Death and Shadows (n.) Little 1999 [see below; Michigan] #

• Underneath Every Stone (n.) Little 2000 [Matt Gabriel; Michigan] #

• Ricochet (n.) Little 2002 [Lt. Jack Stryker; Michigan] #

• Tears of the Dragon (n.) Allison & Busby 2004 [Chicago, 1931; the era of Al Capone] #

I’ve already informed Al that he omitted Matt Gabriel as a series character in Death and Shadows. Gabriel is the sheriff for Blackwater Bay, a sleepy backwater resort town that over the years has have more than its share of unusual mysteries to solve. Jack Stryker, who’s a lieutenant for the police force a few towns over, makes a cameo appearance in Death and Shadows – never in person, only by telephone.

Here’s a question for you. How are hospitals and serial killers alike? Answer: I don’t usually read mysteries in which either one is involved, and here I violated my own rules twice, as that’s exactly what kind of mystery this is – one in which the staff and patients in a private nursing home are found murdered, one by one.

As I pointed out earlier, Matt Gabriel is the local sheriff, but as it turns out, he’s neither of the two primary leading characters, the first being physiotherapist Laura Brandon. She’s the niece of the owner of Mountview Clinic, and extremely interested in learning how her friend and predecessor for the position was murdered. The second of the ad hoc sleuthing pair that gradually develops is Tom Gilliam, a patient who’s withdrawn well into himself since the mishap iy was that forced him off Jack Stryker’s police force.

Another reason why I surprised myself in reading this book is that it is nearly 380 pages long, and in small print too. A hospital setting, a possible psychotic killer on the loose, and a book twice as long as my usual reading fare. You’d think it would be a matter of three strikes and out, but not so. This book kept me up reading for several nights in a row. I was able to put it down, but the next evening I couldn’t resist, and I was back reading it again.

Maybe because the opening two or three chapters read exactly like a gothic novel, with a young(ish) girl coming fresh into a new mysterious and slightly spooky setting. A manor house, a hospital – it makes little difference. Maybe because in 380 pages there is an ultra-abundance of clues to be puzzled over, with lots of secrets on the part of almost everybody, broken hand railings, a local legend called the Shadowman. Maybe because of the many, many red herrings and false trails to follow and double back upon. Delicious!

Mon 16 Jul 2007

Posted by Steve under

Authors ,

AwardsNo Comments

KEN BRUEN – The Dramatist. Nominated for Best Private Eye Hardcover Novel of the Year, 2007.

St. Martin’s, hardcover, March 2006. Trade paperback: March 2007.

Book Description:

Seems impossible, but Jack Taylor is sober – off booze, pills, powder, and nearly off cigarettes, too. One reason he’s been able to keep clean: his dealer’s in jail, which leaves Jack without a source. When that dealer calls him to Dublin and asks a favor in the soiled, sordid visiting room of Mountjoy Prison, Jack wants to tell him to take a flying leap. But he doesn’t, can’t, because the man’s sister is dead and the guards have called it “death by misadventure.” But he says that can’t be true and begs Jack to have a look, check around, see what he can find. “Finding” is exactly what Jack does, with varying levels of success, to make a living. But he’s reluctant, maybe because of who’s asking or maybe because of the bad feeling growing in his gut. Never one to give in to bad feelings, or to common sense, Jack agrees to the favor, though he can’t possibly know the shocking, deadly consequences to which this simple request will lead. There’s no question that Jack will understand soon, sooner than he knows, in this dark, lethal, fast and furious novel from the new master of crime fiction.

About the Author:

Ken Bruen spent 25 years as an English teacher in Africa, Japan, Southeast Asia, and South America. He has been a finalist for the Edgar, Anthony, and Barry Awards, and has won a Shamus and a Macavity. He lives in Galway, Ireland.

Review Excerpts:

Publishers Weekly: “By now, readers know the Bruen formula of the downward spiral, but there’s no denying the effectiveness of the tough dialogue, the crisp scenes and Taylor’s weary, crumpled-jacket appeal. Nor can many writers in any genre evoke a seedy urban Ireland as well as Bruen. Few, too, can continue to deliver interesting stories and even more interesting character studies. With a riveting mystery and a deftly rendered protagonist, Bruen recaptures the immediacy and the impact of the first two novels in the series.”

AudioFile: “… while the story is fascinating and perfectly delivered, it sometimes seems like a story told by a long-winded guy at an Irish pub with a pint of Guinness and a love of his own voice.”

Booklist: “Readers who worry that Taylor’s tenuous sobriety will water down either his cranky personality or the generally offbeat appeal of Bruen’s books needn’t be concerned. This one sports the same great mix of curmudgeonly observations and unpredictable cultural references that has won Bruen a devoted cadre of fans. But while no one reads him for the detection, the plot here exceeds his own standards for casualness, and the double-noir ending feels tacked on. The prolific Bruen, still good, needs to catch a gear if he wants to avoid spinning his wheels.”

Previous Jack Taylor novels:

The Guards. St. Martin’s, hardcover, January 2003. Trade paperback: January 2004.

The Killing of the Tinkers. St. Martin’s, hardcover, January 2004. Trade paperback: February 2005.

The Magdalene Martyrs. St. Martin’s, hardcover, February 2005. Trade paperback: February 2006.

Mon 16 Jul 2007

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Whenever I visit a foreign-language website and click the mouse for an electronic translation, I am reconfirmed in my judgment that of all the Ed Woods of the written word whose genius for mangling the language has enriched my reading life for decades, my computer is second to none.

May I give a for instance? Night and Fear, a collection of stories by Cornell Woolrich that I put together a few years ago to celebrate the centenary of his birth, was recently published in Italian by Feltrinelli Editore. Here’s what I learned about the book from various Italian websites, Englished by my trusty computer. “In order to from birth celebrate the one hundred years of the ‘father of noir’ the Cornell Woolrich, its biographer Francis M. Nevins has collected… fourteen storys escapes on reviews pulp.”

Of “New York Blues,” the final tale in the collection, which “exited posthumous in 1970,” I was told that it’s “a splendid compendium, a epitaffio that it encloses in little pages all the reasons of the fiction of Woolrich: stilistico virtuosismo, evocativa force, dominion of the solitudine, struggimento for impossible loves, madness, desperation and dead women, that is all the colors of the buio.” Woolrich evokes “the tension of a city noir for excellence but in whose comparisons a visceral and unconditioned love can be nourished, nearly it blinds to you from its lights and the migliaia of dowels of solitudini that of it make the greatest agglomerate than history that the humanity could conceive….”

Woolrich’s New York “is a blues warm alternated to a jazz isterico, is a place where however it wants courage to us, is for living that in order to kill, is a cigarette to the poison with which you play the life in one night whichever.”

So that’s what Woolrich was all about! I was wondering.

Flitting from the master of noir to his nearest rival, I recently stumbled across a factoid about David Goodis which seems not to have surfaced before. It’s long been believed that Warner Bros., to whom Goodis was under contract in the late 1940s, did nothing with the multiple screenplays he wrote and later adapted into his novel Of Missing Persons (1950).

It turns out however that they did. Those screenplays were the source of “False Identity,” an episode of WB’s 60-minute TV series Bourbon Street Beat, which was aired on ABC during the 1959-60 season and starred Andrew Duggan and Richard Long as a pair of New Orleans private eyes. Air date was May 23, 1960. William J. Hole, Jr. directed from a teleplay by “W. Hermanos,” the house name used by just about everybody who wrote under the counter for WB during the then ongoing writers’ strike. Featured in the cast were Lisa Gaye, Irene Hervey and Tol Avery. How much authentic Goodis material survived the trip through the Warner Bros. TV sausage factory? I’d guess not a whole lot.

Flitting from fiction to film, I’ve also recently discovered the existence of a previously unknown work by my old friend Joseph H. Lewis (1907-2000), who is best known of course as the director of noir classics like Gun Crazy. During the late Fifties and early Sixties when Joe directed 51 episodes of Four Star’s hit TV series The Rifleman over its five-year run, he also helmed a few segments of other Four Star shows like The Detectives, and also, as I learned a few weeks ago, an episode of the Dick Powell Theater (NBC, 1961-63), a 60-minute anthology series.

“The Hook” (March 6, 1962) is about an investigator for the California Attorney General’s Office (Robert Loggia) who comes to suspect that the rule of a powerful underworld boss (Ray Danton) is about to be challenged by a former mob kingpin (Ed Begley) just released from prison. Finding out about this film was easy. The hard part begins when I try to track down a copy.

Like everyone who went to school when I did, I had great gobs of poetry shoved down my throat in my English classes, but I never developed a fondness for it except for what I discovered on my own, like the hilarious verses of Ogden Nash. My first sale to Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine more than 35 years ago was a piece of criminous doggerel in the Nash manner, and every so often a poem has figured in one of my stories or novels — for example, the toad quotations from Shakespeare, Kipling and Karl Shapiro in “Toad Cop.”

But those facts plus my having lived a block from Howard Nemerov between about 1980 and his death hardly qualify me as an authority on poetry. So it was rather odd that several months ago I was offered a princely fee by the Poetry Foundation, which has an endowment in the megamillions, to write an essay for its website on the links between poetry and crime fiction. That piece, along with Ed Park’s excellent discussion of poetry in the novels of Harry Stephen Keeler, is now a few clicks away from anyone with a computer at www.poetryfoundation.org.

The final version of my brief essay discusses only Hammett, Chandler and Ross Macdonald. But that thing went through more drafts than one of the toads in “Toad Cop” has warts, and a slew of interesting interfaces between poetry and mystery fiction wound up on the electronic cutting-room floor. This is why I plan to turn the final item in several future columns into a sort of Poetry Corner.

For space reasons I’ll keep my first specimen short and light. Fatal Descent (1939) was the only collaboration between two of the giants of the golden age of detective fiction, John Rhode and Carter Dickson (John Dickson Carr). Its plot seems to have been devised by both men but the writing is all Carr, a fact for which anyone who’s read Rhode’s dry-as-dust prose will thank whatever gods there be.

Investigating the impossible murder of a publisher while alone in a descending elevator, Scotland Yard’s Inspector Hornbeam takes time out to read a newspaper account of a speech by one of the suspects entitled “A Peak in Darien.” The inspector is unversed (sorry, couldn’t resist) in poetic allusion. “What’s Darien?” he asks Dr. Horatio Glass. “I’m not sure,” that brilliant amateur sleuth replies. “It’s a place where you’re supposed to stand silent and look at the Pacific. Why are you interested in all that guff, anyway?”

To the poetryphiles who read this column I promise that my next specimens will be more respectful.

Sat 14 Jul 2007

Posted by Steve under

Authors ,

ReviewsNo Comments

MICHAEL GILBERT – The Black Seraphim

Penguin; US paperback reprint; 1st printing, 1985. Hardcover editions: Hodder & Stoughton (UK), 1983; Harper & Row (US), 1984.; Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1]. Other paperbacks: Hamlyn (UK), 1984; Mysterious Press (US), 1987.

Mr. Gilbert was born in 1912, which would have made him 73 when this book was first published, and by no means was he finished as a writer. By my count there have been 14 more novels and collections that came after this one, including the provocatively titled The Mathematics of Murder, a collection of short stories that was published in England in 2000. No US edition seems to have been forthcoming, and [at the time I write this] no copies of any persuasion show up on ABE at all.

The series characters in The Mathematics of Murder belong to the London solicitors’ firm of Fearne and Bracknell, with several of the stories being previously published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, and that is where perhaps they might be most easily tracked down. There are no series characters in The Black Seraphim, to which I will return to in a moment, but over the years several detectives and other starring characters have made their way in and out of Gilbert’s novels and short stories. These include Inspector Patrick Petrella, Inspector (later Superintendent) Hazlerigg, Commander Elfe, solicitor Henry Bohun, Jonas Pickett, the espionage team of Samuel Behrens and Daniel John Calder (Petrella, Pickett and and Elfe also make various crossover appearance in several of their adventures), and Luke Pagan, about whom I know little, but whose cases seem to all have taken place around the time of World War I.

Gilbert’s most recent book is a collection of short stories, The Curious Conspiracy and Other Crimes, which was published by Crippen & Landru in 2002. (C&L also did The Man Who Hated Banks And Other Mysteries, which came out in 1997.) The most recent novel that Gilbert has written seems to have been Over and Out (Hale, 1999), a Luke Pagan entry. Going back to the beginning of his career, Gilbert’s first work of crime fiction was Close Quarters (1947), a mystery in which Hazlerigg has the starring role, a work of detective fiction which falls, definitely and definitively, within the so-called “Golden Age” or classical tradition.

Which gets us circled back around to The Black Seraphim, which – if you’re still with me — is a “Golden Ager” as well, at least in an modernized sense. The romance that’s involved is a little more amorous than it would have been in 1933, for example, and in a few other ways which involve how the story itself is allowed to develop, which I’ll get back to in a moment.

From the beginning, though, while the year this novel takes place is not stated in any specific fashion, it can easily be assumed to be 1983, the year of its publication. Nothing overtly suggests otherwise. But taking place as it does in a small cathedral town, with much of the action behind the walls of the cathedral grounds and in effect isolated within, the book produces the feeling that a massive slidestep back into time has occurred. Save for a few modern conveniences, the year could have as easily been 1933, a mere fifty years before.

James Scotland, a young pathologist sent to Melchester for a little R&R (rest and recovery), soon discovers that jealousies and bitter rivalries can exist (nay, thrive!) just as well in a theological college as well as it can in academia, to name another scene of the crime where the stakes are as equally high (or low, depending on your point of view). Town and gown antagonisms are an equally crucial part of the mix.

Having not read Gilbert recently, if ever, other than one or two short stories, I was surprised a bit at the elements of rowdy schoolboy humor – I’d have thought it was more in Michael Innes’s field of expertise, if you’d asked me ahead of time – but when the murder occurs, it becomes clear that a serious turn has been taken.

And being a book produced later in Gilbert’s career, it is not too surprising that within its pages he turns philosophical, as age and wisdom come upon him, and it is here where I believe the major deviation from the Golden Age comes in.

I hope you don’t mind a lengthy sort of quote. This is from page 182, and is a discussion between Scotland and a lady whom he is rapidly becoming fond of. They are discussing how the investigation is proceeding, and Scotland speaks first:

He said, “Anyway, it proves that I was right and you were wrong.”

“About what?”

“Surely you can’t have forgotten. What you said when we were on that walk. About scientists prying into matters they ought to leave alone and coming up with the wrong answers. They came up with the right answer this time.”

This was rash of him. Amanda said, “You’ve got it all wrong, Buster. What I said was that scientists never know when they’ve reached the place where they ought to stop. Well, you’ve reached it now, haven’t you?”

“I doubt if there’s much more information to be extracted from those samples.”

“Right. So you stop.”

“Your father wouldn’t agree with you. He said, ‘When once you have put your hand to the plow, turn not back.’”

“Exactly,” said Amanda triumphantly. “But when you’ve reached the end of the last furrow, you’ve got to stop. You don’t want to start plowing up the road.”

This is not your usual lovers’ tiff, I think you will agree. There are two brief scenes (pages 184 and 191) that puzzlingly do not seem to fit in with any of the explanations that come later, but what at first is the most – let’s say disconcerting – is that the final unraveling takes place totally outside of Scotland’s presence. It’s anti-climactic, one thinks, initially, and then, given some thought, perhaps not.

Much is made of Scotland’s age. He’s but 24, and he’s young enough to recover from the blows of fate that his stand (see above) has dealt him. In what may be a final twist, not in terms of solving the case, but rather in terms of who –- it is another man, not Scotland but one much older, who, in the final few pages, looks back, and who decides on his own that justice has been done, and on its own merits.

It took me a while, but I finally came around. This is a fine piece of work.

PostScript: The title is taken from a line in a poem by the French poet Alfred de Musset, concerning the concept of a blessed wound, from which at length Scotland will recover: “une sainte blessure; que les noirs séraphins t’ont faite au fond de coeur.”

UPDATE [07-14-07] Michael Gilbert died in 2006, nearly two years after this review was written. For a comprehensive online overview of his career, including a bibliography of his mystery fiction, this webpage will do very nicely, I think.

Sat 14 Jul 2007

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

A REVIEW BY MARY REED:

R. AUSTIN FREEMAN – The Stoneware Monkey.

Hodder & Stoughton, hardcover, 1938. Dodd Mead & Co, hardcover, 1939. Paperback reprints: Popular Library #11, 1943. Dover, with The Penrose Mystery, 1973.

Dr James Oldfield is doing a stint as a locum-tenems in the small country town of Newingstead. Biking back after a professional call, he stops on a country road to smoke a pipe and enjoy the pleasant evening air. Investigating a cry for help from nearby Clay Wood, he discovers Constable Alfred Murray dying from a fatal blow dealt with his own truncheon.

Constable Murray had been chasing whoever stole a packet of diamonds worth some 10,000 pounds from Arthur Kempster. A dealer in London, Kempster lives locally and carelessly left the gems unattended, allowing the thief to pop in a window, take them, and scarper. Kempster runs after the thief, engaging Constable Murray in the pursuit. Thief and constable outpace Kempster so there is no witness to the murderous assault, and the criminal escapes by stealing Dr Oldfield’s bike.

The scene then shifts to Dr Oldfield’s practice in Marylebone, London. One of his patients is Peter Gannet, who lives at 12 Jacob Street — a thoroughfare with more than its ration of crime! Gannet shares the studio behind his house with his wife’s second cousin, Frederick Boles, a maker of jewelry. Gannet is a potter, and among creations displayed on his bedroom mantelpiece is the titular statuette. Gannet’s works do not impress Dr Oldfield much, for he describes them as “singularly uncouth and barbaric”, exhibiting “childish crudity of execution”. Be that as it may, Gannet’s illness defies all the treatments prescribed, and so Dr Oldfield, a former pupil of Dr Thorndyke, Freeman’s primary series character, decides to consult his old teacher about the case.

They make a startling discovery, pointing to an attempt to murder Gannet. Is the culprit Mrs Letitia Gannet, who does not appear to get along with her husband? Or is it Boles, suspected of being over familiar with Mrs Gannet? Might it be the Gannets’ servant, or perhaps even an unknown outside party? Nothing is established and things return to normal in the household but after Mrs Gannet returns from a holiday she finds her husband is missing and Boles has disappeared. Then a startling discovery is made and Thorndyke is called upon to solve the mystery.

My verdict: Although I guessed whodunnit and why before reaching the closing stages of the book, it was more by intuitive leap rather than Dr Thorndyke’s careful step by step building up of a case, so I missed some of the more subtle clues planted along the way. The novel features perhaps one too many coincidences for my taste, although I got a kick from RAF’s nod to The Jacob Street Mystery. There’s a fair bit of interest in the explanation of the procedure to be followed in bringing a capital case, while the portion devoted to pottery technique may make readers’ eyes glaze, no pun intended, but also forms an important part of the narrative.

All in all, however, I found this one of RAF’s less interesting works, so give it a mark of B minus. Other readers will probably enjoy it more.

Etext: http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks07/0700811.txt

Sat 14 Jul 2007

From Publishers Weekly online, 07-13-07:

Edwin McDowell, whose 26-year career as a reporter with the New York Times included a number of years covering book publishing, died Tuesday at his home in Bronxville, N.Y. He was 72. McDowell joined the Times in 1978 after working at several different newspapers, including the Wall Street Journal. McDowell was also the author of three novels and in 1964 wrote Barry Goldwater: Portrait of an Arizonian.

From Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

McDOWELL, EDWIN (Stewart) (1935-2007)

* The Lost World (St. Martin’s, 1988, hc) [New York City, NY]

Book description:

“The darker side of New York City comes to vivid life in this troubling yet touching story of a relationship between two very unlikely people and how this relationship changes their lives. New York ‘Free Press’ newspaperman Alex Shaw covers Times Square as his beat. And young Leonardo Ruis prowls the streets there trying to survive amid the drugs, danger, and decadence. After a violent first encounter, where Leonardo and his gang mug Alex, they both discover a mutual interest and a way to help each other. As their relationship develops, the reader is confronted with the horrors of street life in New York City.”

Review excerpts:

New York Times: “Edwin McDowell, who covers publishing for The New York Times, has taken a look at what he calls ‘the lost world’ and has built his fiction upon a stock of horrified observation of the dopers, muggers and losers who scurry among the blank new constructions and such isolated monuments as the Harvard Club. […]

“In his third novel Mr. McDowell is aiming more for a Frank Norris documentary, sometimes irately sociologizing ‘the whole panoply of pathologies,’ rather than a William S. Burroughs hallucinatory celebration. Though the madness appalls him, occasionally there are flashes of ironic invention, as when he evokes a mugger’s parrot, trained to say on command, ‘Give me all your money!’

“In the end, the writer ties it all up but doesn’t blink. The lost boy is not found, the wild boy is not saved and Alex Shaw and his Jill are hurtling through Times Square in a cab, sending a jaywalker scrambling. This, of course, is not an invented irony. And come to think of it, probably the mugger’s parrot isn’t, either.”

Publishers Weekly: “Grittily realistic local color adds credibility and interest to this well constructed, suspenseful tale. Alex Shaw, like the author (To Keep Our Honor Clean) a New York journalist, covers the Times Square area, and one day is approached by a young hoodlum nicknamed ‘Dingo,’ teenage son of an aging hooker, who lives on the streets. […] What he learns from Dingo about respectable businessmen who prey on the bodies of young boys and girls may not be news to the reader, nor is McDowell’s theory, promulgated through Alex, of intentional neglect by real-estate moguls eager to make bucks once the area becomes completely desolate. But his mix of scrofulous lowlifes and crusty journalists is authentic, and the novel is suspenseful, funny and sometimes surprisingly tender.”

Fri 13 Jul 2007

Following up on my comments after Steve’s review of Manning Coles’ No Entry:

In Drink to Yesterday, as Hambledon and Saunders/Kingston are escaping toward Ostend, they stop to requisition gas and oil from a German depot of some sort. There are some British POWs at the depot making pointed remarks, and one of them refers to Hambledon as a “wee fat man.” Now, he’s dressed as a German major and is probably wearing a greatcoat, so he may not be all that portly, but still…

Earlier, Saunders describes a non-existent bad guy as someone taller than himself, and says the man was five-eight or five-ten, which would imply that Saunders was of average height; that might make Hambledon sound shorter in the scene described above. But Saunders was impersonating the major’s driver, so he may have been seated the entire time, in which case the POW would not have used him as a reference for Hambledon’s height. Who knows? My guess would be Tommy was about five-seven or five-eight and well-fed; the POWs were pretty skinny, I’d imagine, so anyone who wasn’t in their condition would probably appear heavier than he really was.

On page 1 of A Toast to Tomorrow Hambledon as Lehman is described as “short and cheerful.” Several pages later, after he’s surfaced to British Intelligence (without identifying his job in Germany) he’s described by the agent he’s put across the Belgian border as “a nondescript little man, grey eyes, rather ginger hair going grey, short but not fat, thin face with duelling scars across his right cheek, quick, energetic walk, rather a pleasant voice, cheerful-looking fellow, looked as though he could see a joke. Short nose, wide mouth, rather thin-lipped, square jaw.” Both those descriptions are in 1933.

When he is recovering from the near-drowning in hospital in 1918 the doctor thought he was in his late twenties.

I think that’s as much as we’re gonna get.

Fri 13 Jul 2007

Hi Steve,

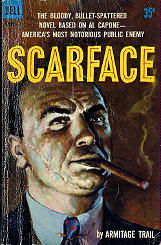

Please find below a brief biography (well, the only one I have found) on the writer who, as Armitage Trail, wrote the novel Scarface.

I wonder if anyone has ever done any research to track down the pseudonymous work mentioned in it. I asked Victor Berch who knows little more — apparently he could not even find him in the census for the years he was alive. (Apparently his brother, also difficult to trace in official records, wrote over 20 episodes for the Addams Family [television show] amongst other work).

Just wonder if he is worth putting in your blog to see if anyone can add to the bio?

Armitage Trail was a pseudonym for the American author Maurice Coons. The son of a theatrical impresario who managed the road tours of the New Orleans Opera Company, and also manufactured furniture and farm silos, Maurice Coons left school at 16 to devote all his time to writing stories. By 17 or 18, he was already selling stories to magazines. By his early twenties he was writing whole issues of various detective-story magazines under a great assortment of various names. And at 28 — after going to New York to write more stories, and from there to Hollywood to write movies — he dropped dead of a heart attack at the downtown Paramount Theatre in Los Angeles.

At the time of his death, he weighed 315 pounds, had a flowing brown moustache, and wore Barrymore-brim Borsalina hats. He was survived by his brother, humorous writer Hannibal Coons.

Maurice Coons gathered the elements for Scarface when living in Chicago, where he became acquainted with many local Sicilian gangs. For a couple of years, Coons spent most of his nights prowling Chicago’s gangland with his friend, a lawyer, and spent his days sitting in the sun room of his Oak Park apartment writing Scarface. He never did meet Al Capone, who was the inspiration for his immortal character, though Capone was very much alive when his book was published.

When Howard Hughes was making plans to produce the movie, Coons wanted Edward G. Robinson to play the leading role because of his resemblance to Capone but being Hollywood, it ended up with Paul [Muni] playing Scarface, a different-looking sort of man altogether. The author did not live to see the picture, but Al Capone did, and screenwriter Ben Hecht had to talk fast to convince his henchmen that Scarface was not based on him. Scarface was also made into a film in 1983, directed by Brian de Palma and starring AI Pacino. Armitage Trail’s only other surviving novel is The Thirteenth Guest ( 1929). Both his novels prefigure the birth of hard-boiled fiction and Black Mask magazine.

From Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

COONS, MAURICE (1902-1930); see pseudonym Armitage Trail.

TRAIL, ARMITAGE; pseudonym of Maurice Coons.

* * Scarface (Clode, 1930, hc) [Chicago, IL] Long, 1931. Film: United Artists, 1932 (scw: Fred Palsey, W. R. Burnett, John Lee Mahin, Seton I. Miller, Ben Hecht; dir: Howard Hawks). Also: Universal, 1983 (scw: Oliver Stone; dir: Brian De Palma).

* * The Thirteenth Guest (Whitman, 1929, hc) Film: Monogram, 1932 (scw: Francis Hyland, Arthur Hoerl, Armitage Trail; dir: Albert Ray). Also: Monogram, 1943, as Mystery of the Thirteenth Guest (scw: Charles Marlon, Tim Ryan, Arthur Hoerl; dir: William Beaudine).

Fri 13 Jul 2007

Posted by Steve under

AwardsNo Comments

Private Eye Writers of America

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 13, 2007

CONTACT: Ted Fitzgerald – Shamus Awards Chair tedfitz [at] msn.com

PRIVATE EYE WRITERS OF AMERICA ANNOUNCES 2007 SHAMUS AWARDS NOMINEES

The Private Eye Writers of America (PWA) is proud to announce the nominees for the 26th annual Shamus Awards, given annually to recognize outstanding achievement in private eye fiction. The 2007 awards cover works published in the U.S. in 2006. The awards will be presented on September 28, 2007, at the PWA banquet in Anchorage, Alaska, during the weekend of the Bouchercon World Mystery Convention.

2007 Shamus Awards Nominees (for works published in 2006)

Best Hardcover

The Dramatist by Ken Bruen (St. Martins Minotaur), featuring Jack Taylor

The Darkest Place by Daniel Judson (St. Martins Minotaur), featuring Reggie Clay

The Do-Re-Mi by Ken Kuhlken (Poisoned Pen Press), featuring Clifford and Tom Hickey

Vanishing Point by Marcia Muller (Mysterious Press), featuring Sharon McCone

Days of Rage by Kris Nelscott (St. Martins Minotaur), featuring Smokey Dalton

Best Paperback Original

Hallowed Ground by Lori G. Armstrong (Medallion Press), featuring Julie Collins

The Prop by Pete Hautman (Simon and Schuster), featuring Peeky Kane

An Unquiet Grave by P.J. Parrish (Pinnacle), featuring Louis Kincaid

The Uncomfortable Dead by Paco Ignacio Taibo II and Subcomandante Marcos, translated by Carlos Lopez (Akashic Books), featuring Hector Belascoaran Shayne

Crooked by Brian M. Wiprud (Dell), featuring Nicholas Palihnic

Best First Novel

Lost Angel by Mike Doogan (Putnam), featuring Nik Kane

A Safe Place for Dying by Jack Fredrickson. (St. Martin’s Minotaur), featuring Dek Elstrom,

Holmes on the Range by Steve Hockensmith (St. Martin’s Minotaur), featuring Gustav “Old Red” Amlingmeyer

The Wrong Kind of Blood by Declan Hughes. (Wm. Morrow), featuring Ed Loy

18 Seconds by George D. Shuman. (Simon & Schuster), featuring Sherry Moore.

Best Short Story

“Sudden Stop” by Mitch Alderman. Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, November 2006, featuring Bubba Simms

“The Heart Has Reasons” by O’Neil De Noux. Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, September 2006, featuring Lucien Kaye

“Square One” by Loren D. Estleman. Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, November 2006, featuring Amos Walker

“Devil’s Brew” by Bill Pronzini. Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. December 2006, featuring John Quincannon.

“Smoke Got In My Eyes” by Bruce Rubenstein. TWIN CITIES NOIR (Akashic), featuring Martin McDonough

PWA was founded in 1981 by Robert J. Randisi to recognize the private eye genre and its writers. Previous Shamus winners include Lawrence Block, Ken Bruen, Harlan Coben, Max Allan Collins, Michael Connelly, Robert Crais, Brendan DuBois, Loren D. Estleman, Carolina Garcia-Aguilera, Sue Grafton, James W. Hall, Steve Hamilton, Jeremiah Healy, Dennis Lehane, Laura Lippman, John Lutz, Bill Pronzini, S.J. Rozan, Sandra Scoppettone and Don Winslow

« Previous Page — Next Page »