August 2007

Monthly Archive

Thu 9 Aug 2007

On July 14th I received an email from Al Hubin, author of Crime Fiction IV, about a new discovery that he had made:

“FYI…to my considerable surprise, I found in Philip MacDonald’s CA [Contemporary Authors] entry the listing of The Sword and the Net as by Warren Stuart. I don’t think anyone’s made this observation before…”

Here’s the Warren Stuart entry as it is (or was) in CFIV:

STUART, WARREN

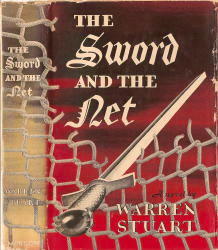

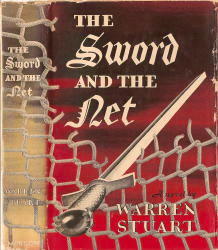

* The Sword and the Net (Morrow, 1941, hc) Joseph, 1942.

There’s nothing remarkable about the entry. There are many, many authors with only a single title included in CFIV, about whom nothing is known, neither the author nor the book.

Al, of course, did the sensible thing. He ordered a copy of the book immediately. As soon as he received it, he read through it and send me a copy of the dust jacket cover and the blurbs that describe the book on the inside flaps of the dust jacket:

Very occasionally a publisher presents a novel with a story so packed with exciting action and dramatic suspense that he hesitates to reveal any significant part of the plot for fear of spoiling the enjoyment of the reader.

The Sword and the Net

By WARREN STUART

is just that kind of book – so thrilling and unexpected that we are deliberately withholding all description beyond the bare essentials.

THE TIME of the story is 1940-41.

THE PLACE – Berlin and Sweden briefly, then New York and California

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS:

OTTO FALKEN: Aristocratic young German, war ace and hero …

CAROLYN VAN TELLER: The rich, beautiful widow of a New York banker …

[continued on back flap]

RUDOLPH ALTINGER: Ostensibly successful head of a large construction firm in San Francisco …

GUNNAR BJORNSTROM: A withered, kindly, cheerful old gentleman originally from Sweden …

WALDEMAR INGOLLS: A German officer in the last war, but for years resident of California and an American citizen in the highest sense of the word …

CLARE, his daughter: A courageous, lovely girl as bitterly anti-Nazi as her father …

Other Characters: Nazi officials and officers, Swedish peasants, secret agents; seamen; Americans of every type; Nazi saboteurs and spies.

A spy story? Well, perhaps; but much more than that, for the author has blended a subtle development of character and the poignant love story of two people into a tale so packed with action that the pages almost turn themselves.

Before getting to Al’s first-glance opinion of the book, I’ll point out the story also appeared in Two Complete Detective Books, Number 15 (Fall, 1942). The lead novel in that issue was Death Turns the Table, by John Dickson Carr, and of course I have a cover image to show you, one found on eBay at some time in the past.

Here’s Al’s initial reaction: “The story is quite unlike anything I recall of MacDonald’s work … slow moving, interesting but not compelling or fully persuasive. If MacDonald actually wrote it (and we have no other candidates), I’m certainly not surprised it was published under a pseudonym — and one which, so far as I know, was not publicly acknowledged during his lifetime.”

Truthfully, though, Al and I have been scooped on this rather unexpected find. In the latest issue of CADS, #52, which arrived just days ago, is a short announcement of the discovery by Tony Medawar, and more, a short synopsis and review of the book by that noted scholar of mystery fiction himself.

Since I can do no more than a few excerpts from his comments, a few excerpts are all you are going to get. Otto Falken, the hero (or rather anti-hero) whose actions the book follows, is selected by Hitler for a secret mission. Eventually he is required to assist a team of saboteurs in this country. From here, I quote:

“… a thriller rather than a detective story, and something of a Hitchcockian thriller at that. […] It is possible that the plot was first conceived for the cinema.

“… the story […] is not unpredictable but […] is compelling and the novel builds to an exciting climax in the hills outside San Francisco. A fascinating addition to the canon of a fascinating writer and well worth the search.”

As the news becomes more widely disseminated, the search is going to be much harder. A word to the wise may already be too late.

PostScript: Tony also mentions in a footnote to his review something else I didn’t know. As “W. J. Stuart,” MacDonald did the novelization of the 1950s science fiction novel, Forbidden Planet (Farrar Straus & Cudahy, hc, 1956; Bantam A1443, pb, 1956).

Also please note: The link to information for CADS is for issue #51,but #52 can be ordered from Geoff Bradley at the same address, but the price has gone up from $11 to $12. Tell him I sent you.

[UPDATE.] 07-28-09. British bookseller Jamie Sturgeon has come across a copy of the first UK edition (Michael Joseph, 1942), and he’s sent me a scan of the dust jacket. He also adds: “Interestingly apart from a ‘puff’ from James Hilton there’s no other blurb or anything else about the plot/author anywhere.”

Wed 8 Aug 2007

Steve,

Your blog entry on John Creasey and the Toff served as a pleasant reminder of the madly-prolific yet now almost-forgotten Creasey. There seemed a time (1960s/1970s) when the shelves on London bookshops were weighed down with Creasey’s Hodder & Stoughton paperbacks.

I was very interesting to read that William Vivian Butler penned the post-1973 Creasey novels. I reached for Butler’s ‘critical study of some enduring heroes’, The Durable Desperadoes (Macmillan, 1973), a warmly nostalgic overview of British gentleman-adventurer literature from the early part of the last century, and discovered the following special note at the beginning of this work:

“John Creasey’s sad death took place while this book was in production. This gives me an additional opportunity to express my gratitude for all his help, and to emphasise that both the book and its preface were shown to him, and met with his warm approval.

“Nothing that I have written about the Toff and the Baron is invalidated by their creator’s death — not even the statement that, while so many similar heroes have fallen by the wayside, they still “stroll nonchalantly on”. John Creasey has left so much posthumous material that new novels in both the Toff and the Baron series will continue to appear until at least 1975, and possibly 1977.”

It is indeed unfortunate that while the Toff books seemed destined to trail in the shadow of Charteris’s The Saint novels (a little unfairly, I always thought), so have two little-known (of course) cinematic adventures featuring Creasey’s calm and daring character.

Released to cinemas merely months apart in 1952 (in the UK), Salute the Toff and Hammer the Toff (both directed by Maclean Rogers for producer Ernest G. Roy at Nettlefold Films), starring the seemingly ever-resilient John Bentley as the Hon. Richard Rollison, seem to have disappeared into B-movie limbo. But during their short existence, Valentine Dyall’s Inspector Grice observed as the Toff traced a missing person (in Salute the Toff) and became involved with a stolen metal formula (in Hammer the Toff). Of course, there is the likelihood that the word ‘dreadful’ is primed for reactivation here.

However, the truly fascinating aspect to these two rarely-seen films is that Creasey himself is credited with adapting the screenplays from his own novels (the 1941 Salute, the 1947 Hammer).

Much like the still-elusive Paul Temple films of the same period (from works by Francis Durbridge), one hopes that the continual scraping of the bottom of barrels for new DVD movie properties may unearth the Toff duo for viewing evaluation in the near future.

Thanks again for an interesting and informative Toff/Creasey piece.

From Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

BUTLER, WILLIAM VIVIAN (1927-1987); see pseudonym Vivian Butler.

* Clampdown (London: Macmillan, 1971, hc) [England]

* Clampdown (London: Macmillan, 1971, hc) [England]

* Gideon’s Fear (Hodder, 1990, hc) [Commander George Gideon; England]

* Gideon’s Force (Hodder, 1978, hc) [Commander George Gideon; England] Stein, 1985.

* Gideon’s Law (Hodder, 1981, hc) [Commander George Gideon; England] Stein, 1985.

* Gideon’s Raid (Hodder, 1986, hc) [Commander George Gideon; England] Stein, 1986.

* Gideon’s Way (Hodder, 1983, hc) [Commander George Gideon; England] Stein, 1986.

* The Lie Witnesses (London: Macmillan, 1971, hc) [England]

* Scare Power (London: Macmillan, 1969, hc) [England]

* The Toff and the Dead Man’s Finger (Hodder, 1978, hc) [Richard Rollison (The Toff); England]

BUTLER, VIVIAN; pseudonym of William Vivian Butler

* Guy for Trouble (Crowther, 1945, hc)

Tue 7 Aug 2007

Posted by Steve under

General[4] Comments

A character-driven detective novel is one in which the plot develops entirely from the people who inhabit it, protagonists and secondary characters both — their psychological makeup, strengths, weaknesses, vulnerabilities, etc. The plot is not created first and the characters inserted to fit the prearranged storyline.

Whodunit, howdunit, detection are all less important than what happens to the people themselves; the impact on them of the crime(s) in which they’re involved; how they and/or the world they live in are altered by these crimes and by other external events, some within their control, some beyond it.

In a character-driven series, the protagonists and those close to them have personal as well as professional lives. And they do not remain the same from book to book; they evolve, change, make mistakes, better their lives, screw up their lives, love, marry, grieve, suffer, rejoice, you name it, the same as everybody else.

A plot-driven detective novel is just the opposite. Characters are subordinate to plot; the mystery, the gathering and interpretation of clues, the solving of the puzzle are of primary focus and importance. If the detectives have personal lives, they’re generally mentioned only in passing and treated as irrelevent.

This is not to suggest that this type is inferior to the character-driven variety; far from it. I’m a great admirer of the Golden Age writers — Carr (particularly), Queen, Christie, Stout — but their books mostly fall into the plot-first category.

The puzzle, the game is everything. Sir Henry Merrivale, Dr. Fell, EQ, Poirot, Nero Wolfe are all superb and memorable creations, but each remains essentially the same from first book to last. There is no evolution, no significant change. The crimes they solve have no real effect on them, or in other than a superficial fashion on the people good and bad whom they encounter.

One reads their adventures mainly for the cleverness of the gimmicks and the brilliance of the deductions (and in the cases of Wolfe and Archie for the witty byplay, and of H-M for the broad and farcical humor). With the exception of Wolfe and Archie, we never really get to know any of them all that well; and even with that inimitable pair, there are no significant changes in their lives or their relationship with each other.

The private eye fiction of Hammett and Chandler is likewise plot-driven (remember Chandler’s oft-quoted remark that when he was stuck for something to happen, he brought in a man with a gun?). The mystery is dominant. As memorable as Sam Spade and the Continental Op and Philip Marlowe are, they’re larger-than-life heroes who remain pretty much the same over the course of their careers.

This is true even in The Long Goodbye, which many consider to be Chandler’s magnum opus (I don’t, but that’s another story); Marlowe’s complex relationship with Terry Lennox and its results, while a powerful motivating force, has no lasting or altering effect on Marlowe’s life.

Ross Macdonald’s novels, on the other hand, are character-driven to the extent that the convoluted storylines devolve directly from the actions past and present of the large casts of characters; but Lew Archer is merely an “I” camera recording events. His life and career remain unaltered by the crimes he solves or any other influences. We hardly know him; he hardly seems real.

Contemporary private eye fiction tends to be primarily character-driven, in the sense that I used the term above. The cases undertaken by Thomas B. Dewey’s Mac, for instance, evolve from the complexities and eccentricities of the individuals he encounters; crime and violence have a profound effect on him as well as on those individuals, in subtle as well as obvious ways.

The same is true of Hitchens’ Long Beach private eye Jim Sader in Sleep with Slander, a book I’ve called “the best traditional male private eye novel written by a woman.” And of Lawrence Block’s Matt Scudder. And of Marcia’s Sharon McCone (see Wolf in the Shadows, her Shamus-nominated Vanishing Point). And of my “Nameless” series (Shackles, Mourners). All, for better or worse, character-driven and character-oriented. Which is why our readers continue to read us.

Tue 7 Aug 2007

The latest batch of covers uploaded to Bill Deeck’s Murder at 3 Cents a Day website are those for the William Godwin, Inc., 1933-1936.

Here’s Bill Pronzini’s introduction to the page containing the publisher’s line of mystery fiction:

William Godwin, Inc. was best known for the softcore sex novels they published from 1931-38, by such well-known practitioners as Jack Woodford and Fan Nichols; these had provocative cover art and were considered pretty steamy for their time, though they are tame today.

The first mystery to carry the Godwin imprint was Wesley Price’s Death Is a Stowaway (1933), a title inadvertently left out of the Godwin listing in Murder at 3c a Day. The three Timothy Trent (Carl Malmberg) titles are excellent hardboiled tales, as is Alan Williams’ Cainesque Room Service.

In 1935 Godwin published several British mysteries on a cooperative deal with the king of the U.K. lending library publishers, Wright & Brown; these all used the original W&B dust jacket art, most of it by Micklewright. The Godwin editions had very poor sales, as evidenced by the fact that copies are extremely difficult to find today, and the arrangement with W&B was abandoned after only a single year.

Mon 6 Aug 2007

As part of Al Hubin’s ongoing Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, I uploaded Part 17 yesterday morning. I’ve not had a chance to add many of my usual enhancements, links, covers and other annotations, but this latest installment is online and ready for viewing.

Of perhaps of major interest are (a) the discovery of a hitherto unknown book by Philip MacDonald, under an equally hitherto unknown pen name, and (b) the true identity of thriller writer Wyndham Martyn, whose life was as much a mystery as his books.

Lots of other information, too!

Sat 4 Aug 2007

While technically speaking this blog is still on its August break, the garage is far too hot for me to spend as much time as I should be in getting it organized and “cleaned out.” So I’m doing what I can do inside instead, and that includes working on the Addenda for the Revised edition of Allen J. Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV.

At the moment I’m working on the S’s in Part 3. The following caught my eye a couple of evenings ago, and as a result I spent some time making sure that I had all of the relationships identified and untangled for the four authors who were:

STRANGE, MARK. Joint pseudonym of Adrian Leslie Stephen, Karin Costelloe Stephen, Marjorie Colville Strachey, & Rachel Costelloe Strachey, q.q.v. Under this pen name, the author of one novel in the (Revised) Crime Fiction IV; see below:

Midnight. Faber, hc, 1927. [Academia; England]

Taking the co-authors one at a time, in alphabetical order:

STEPHEN, ADRIAN LESLIE. 1883-1948. Add both dates. Noted psychoanalyst; brother of author Virginia Woolf. Both were members of the Bloomsbury group. Married to Karin Costelloe Stephen, also a physician and psychiatrist. Joint pseudonym with Marjorie Colville Strachey, Rachel Costelloe Strachey & Karin Costelloe Stephen, qq.v.: Mark Strange, q.v.

STEPHEN, KARIN COSTELLOE. 1889-1953. Add both dates. A physician and psychiatrist; married to Adrian Leslie Stephen. Sister of Rachel Costelloe Strachey. Joint pseudonym with Adrian Leslie Stephen, Marjorie Colville Strachey, & Rachel Costelloe Strachey, qq.v.: Mark Strange, q.v.

STRACHEY, MARJORIE COLVILLE. 1882–1964. Add both dates. Sister of British writer & critic Lytton Strachey. Joint pseudonym with Adrian Leslie Stephen, Karen Costelloe Stephen & Rachel Costelloe Strachey, qq.v. : Mark Strange, q.v.

STRACHEY, RACHEL [“RAY”] (PEARSALL CONN), née COSTELLOE. 1887-1940. Add full name. Studied mathematics and electrical engineering before becoming actively involved with the British women’s suffrage movement. Sister of Karen Costelloe Stephen; married Oliver Strachey, a mathematician and cryptographer in the Foreign Office, and brother of Lytton Strachey. Joint pseudonym with Adrian Leslie Stephen, Karen Costelloe Stephen & Marjorie Colville Strachey, qq.v. : Mark Strange, q.v.

If you’re interested in learning more about these jointly related and collaborating authors, the links will get you started, and Google will lead you to more. It has occurred to me to wonder what sort of book they might have written. Was it a spoof of the British thriller novel, with academic overtones, or did they take their story and plot completely seriously?

I can’t answer the question, nor can I provide a color image of the cover. Not a single copy is offered for sale on the Internet; in fact, other than the CFIV page, there’s no mention of the book at all.

For now, it’s yet another mystery.

[UPDATE] 08-20-07. Thanks to Jamie Sturgeon, some information on the book has come to light. Check out this later blog entry.

Sat 4 Aug 2007

In an article entitled “Mysteries That Bloom in Spring,” Time Magazine April 17, 1978, Michael Demarest reported on the Second International Congress of Crime Writers. The conference took place in Manhattan in March and was sponsored by the Mystery Writers of America. You can follow the link to read the entire piece, which is a “state of the art” report on the field of mystery fiction as it was nearly 30 years ago. Of major interest, though, at least to me, is the list of “ten current and compelling exemplars” of the crime fiction novel that’s included at the end.

It is not clear who chose these titles. The implication is that the Congress of Crime Writers had some input, or it may have been Mr. Demarest alone, as he appears to have been fairly knowledgeable of the field. How well the choices stand up I leave for you to decide.

[Thanks to Gonzalo Baeza for pointing the article out to me and the other members of the online rara-avis Yahoo group. Gonzalo’s own blog, Sweet Home Alameda, is in Spanish but is definitely recommended.]

Catch Me: Kill Me, by William H. Hallahan (Bobbs-Merrill; $7.95). New Jersey-based Hallahan, 52, a former adman, won his Edgar with a thriller that scurries from the lower depths of Manhattan to the higher reaches of Washington, D.C., and Moscow, with a side trip to the underside of Rome. Its main sleuths, a burnt-out CIA agent and a doughty Immigration official, set out separately to solve the mystery of the disappearance of a minor Russian poet whose scattered dactyls are the clues to a major East-West confrontation. A masterpiece of bamboozlement, Catch Me is a kind of catch-22 between rival and riven U.S. agencies, written in a style that ranges from hardest-boiled yegg to soufflé, with nothing poached.

Copper Gold, by Pauline Glen Winslow (St. Martin’s; $8.95). A former Fleet Street court reporter who now lives in Greenwich Village, Winslow, fortyish, focuses on swingin’ London’s demimonde with Hogarthian relish. Her world of pushers, prossies, punks and rotting Establishment pillars is counterpointed by the decent, diligent coppers who come a cropper. What might otherwise have been a merely expert Scotland Yard procedural is elevated by Soho low jinks and, believe it or not, a pervasive and finally persuasive romanticism.

The Blond Baboon, by Janwillem van de Wetering (Houghton Mifflin; $7.95). The Dutch-born author, 47, who has sojourned in many exotic places and once lived in a Buddhist monastery in Japan, now inhabits Maine and writes cleaner English prose than many a Yankee aspirant. However, his stories are still set, with occasional departures (The Japanese Corpse), in Amsterdam, where his sleuths have taken over the turf once occupied by Nicolas Freeling’s late, lamented Inspector Van der Valk. Van de Wetering’s latest Dutch treat, starring the familiar trio of Detectives Grijpstra and de Gier and their commissaris, is cerebral, comradely and sensual, within the generous Hollander dollops that make KLM a perennially popular airline.

Nightwing, by Martin Cruz Smith (Norton; $8.95). In a tour de non-force suspense novel that mixes virology and American Indian mythology, Hopi hopes and bureaucratic horrors, Author Smith, 35, weaves an all too believable parable of tribal endangerment. His unlikely detectives, a flaky young Indian deputy and an obsessed paleface scientist, encounter a mass killer of a different sort: a vast horde of plague-spreading vampire bats. Smith, who is one-half Pueblo, explicates the Indian psyche and bat pathology as deftly as he creates blood-filled characters.

Gone, No Forwarding, by Joe Gores (Random House; $6.95). Gores, 46, who was a card-carrying private eye in California before switching to literary license, dissects a Mob-connected conspiracy to sue, harass and murder the Bay Area-based Dan Kearny Associates detective agency out of business. DKA, as in two previous novels, survives – after an adrenaline-pumping, nationwide search for a missing witness, conducted in large part by the niftiest black op in the literature.

Death of an Expert Witness, by P.D. James (Scribner’s; $8.95). Since James, 57, is English and a woman, she is frequently hailed as a worthy successor to Christie, Sayers, Margery Allingham and Ngaio Marsh. James’ knowledge of locale (in this case, East Anglia’s murky, misty fen country) and contemporary mores (some pretty kinky), her familiarity with forensic science (which is what Expert’s plot is mostly about) and keen psychological insight, all mark her as an original. Her seventh and best mystery novel brings back Scotland Yard’s Adam Dalgliesh, who writes offbeat poetry.

The Enemy, by Desmond Bagley (Doubleday; $7.95). One of Europe’s bestselling suspense writers concocts drama of genetic manipulation, incidental assassination, government machination and Russian marination. Bagley, 54, who knows his computers and test tubes, is equally at home with his locales (England and Sweden, in this book) and his personae, who can be both touching and tough. The Bagleyan denouement raises his novel from mere artifice to the artful.

Waxwork, by Peter Lovesey (Pantheon; $7.95). Lovesey’s mysteries are set in late 19th century London, which in too many other authors’ hands now seems exclusively Sherlockian. He writes with accurate verbal and social perception about the upper and lower reaches of Victorian sanctimony and contrivance. Waxwork, 41-year-old Lovesey’s eighth novel, is at once charming, chilling and as convincing as if his tale had unfolded in the “Police Intelligence” column of April 1888.

The Baby Sitters, by John Salisbury (Atheneum; $9.95). John Salisbury is the well-guarded nom de plume of a fortyish British historian, political writer and playwright – which adds spice to his first political thriller right from page 1. It is the story of an Orwellian attempt (in 1981) to turn Britain into a fascist state, led by a fanatical Muslim group riding high on Arab oil and abetted by some of England’s leading politicians. The conspiracy is defused by Bill Ellison, a brilliant Fleet Street digger whose investigative team resembles the London Sunday Times’s muckraking groups. Salisbury gives his improbable tale crackling credibility — and is already working on a sequel.

Talon, by James Coltrane (Bobbs-Merrill; $8.95). In his first suspense novel, James Coltrane – in real life a Hawaii-based lawyer named James P. Wohl, 41 – shows himself a young master of the medium. His antihero, Joe Talon, is a superefficient analyst of satellite photos for the CIA in Manhattan. He is also an unrepentantly laid-back hankerer for the surf-and-grass California scene. When Talon detects a curious and erroneous – or doctored? – cloud cover masking a remote area of Nepal, he bucks the Establishment to prove his suspicions, survives sundry assassination attempts and blows open a nasty conspiracy within the Company. He also manages a rather touching love affair and some motorcycle exploits worthy of Evel Knievel.

Fri 3 Aug 2007

Hi Steve,

Well, Death of a Punk seems never to actually die. I’m flattered that you went to such effort to track me down, although I liked the idea of being the 87 year old guy.

To answer your questions:

I wrote the book because in the 70’s, I was a big Raymond Chandler fan and also an habitué of the nascent Punk Rock scene (although we referred to it at the time as “New Wave”) in the Lower East Side of NYC. I used to hang out at CBGB’s in the early days to hear yet-to-be-signed bands like Television, The Ramones, The Talking Heads, Patti Smith, Blondie, and many other less famous ones. I simply decided to create a kind of fat, bald, failed Marlowe and drop him into the craziness of that scene.

One band I went to see a lot was The Mumps, whose lead singer was Lance Loud of An American Family fame. I got to know his minor-celebrity mother, Pat Loud, who at the time worked at a literary agency. I mentioned to her that I’d written about 40 pages of a trashy detective novel set in the New Wave scene and she said, to my genuine surprise, to send it to her at the agency. She read it and told me that if I finished it, her agency would represent me. I was flabbergasted because I had been writing it simply to entertain myself; I had NO idea of getting it published or even of TRYING to get it published.

Shortly after I finished it, Ann Patty, a young editor at Pocket Books (who is now executive editor at Harcourt), bought it. And the rest, as they say, is history. Or, put another way, it sank like a stone. There were pockets of high volume sales, which not-so-coincidentally were located in the only places in the US at the time where New Wave Rock was popular: NYC of course, LA & SF, but also Cleveland, Boston, Athens, GA, and Seattle. I got a lot of fan mail from those towns.

Foreign rights were sold to Germany (where it went through two printings as Tod eines Punk with the worst cover ever; I’ve never been able to collect royalties) and France, as you found. I sold the movie rights three times because certain producers smelled an album tie-in, and I was paid by one to write a screenplay adaptation, but nothing ever came of it. Is this more than you want to know?

Why has the price skyrocketed? Well, I started buying up copies on the Internet in the early 90’s. I refused to pay more than five bucks per copy and very few cost more than that. Gradually the prices started to climb. I think it was in 1995 that I was astonished to see that a store in Minneapolis wanted $29.95 for it. I even wrote the guy and asked what was up with that. He wrote back that he was buying up all the cheapo copies he could find because they sold for his price as fast as he could list them. In the next few years, the cheapos pretty much disappeared. Soon the average price had risen to about $50. I couldn’t believe it.

I started getting fan mail again because, like you, readers were able to find me. Then, around 5 years ago, I saw one on abe.com for more than $100. I wrote to the vendor in San Diego and asked him why he was charging such an outlandish sum for it. He responded that every copy he listed sold immediately no matter what the price and that the $100 one had also just sold. He told me he was going to raise the price again if he came across more copies. Prices started to climb into three figures and stayed there.

About two years ago, they started selling for lower four figures; I think the post on your blog about those prices must be correct. I can’t believe anyone would actually pay that much in any case. You can get Hemingway first editions for less. As for WHY it’s selling for so much… I think it’s because it’s set in that now-famous time and place, and many of the peripheral characters seem to be based on now-famous people, although I vehemently deny that vicious canard; any resemblance to persons living, dead, or otherwise is purely coincidental and exists wholly in the fevered imaginations of certain wacky readers. Judging from the fan mail, people seem to find it funny and entertaining too.

Why is it scarce? When it came out, it had no advertising budget. Pocket Books was putting all their chips on the paperback edition of The World According to Garp, releasing it with six different covers and a huge promotional budget. The pleasant middle-aged ladies in the publicity department didn’t know what to make of D.o.a.P. (I even had a glowing blurb from Debbie Harry that they refused to use because they hadn’t really heard of her) and advised me to go to bookstores and buy copies to extend its shelf-life.

They set up a few radio interviews but I did most of the promoting myself through my connections in the music world. I did manage to steal a box of promo copies from the PR office, which I distributed as judiciously as I could to media types. While it got rave reviews in hip-but-little-read places like Andy Warhol’s Interview Magazine, the few reviewers in the mainstream press who wrote about it were a bit nonplussed; the Denver Post paired its review of it with an alternate-history novel about World War III by an ex-general . The reviewer segued into the D.o.a.P. portion thusly: “Going from the globe to the gutter…”

I liked that very much. If D.o.a.P. is ever re-published, I want the cover copy to read: “It Goes From the Globe To the Gutter!”

What’s up with Who Killed the Snowman?: After an editorial meeting at Pocket Books, it was decided to change the title to W.K.t.S.? When they told me about the change, they also showed me a mockup of the cover. Basically they wanted to take a book that had to do with the edgy part of the pop music world (which they didn’t understand) and change it to the generic part of the drug culture (which they did understand).

While no expert in marketing, I didn’t think it took much brainpower to understand that marketing a book as though it’s about one thing when it actually isn’t, pretty much guaranteed failure. I went into Ann Patty’s office, stamped my feet, flailed my arms, and pouted until she agreed to try to get it changed back to Death of a Punk. In the end, we prevailed but not before they’d registered the ISBN as Who Killed the Snowman? That’s why one can still find mention of Snowman in hoary medieval databases.

One side story: The cover with “The Punk” was painted by the best Pocket Books house artist, whose name escapes me now. He’d done many classic paperback covers in the 60’s and 70’s. The reason the Punk’s left hand is in that goofy position is that in the original painting he was holding a cigarette.

The same marketing geniuses who’d come up with W.K.t.S? decided that potential buyers who didn’t smoke or who wanted to quit might subconsciously be deterred from buying the book by the presence of the cigarette. As you can imagine, I stamped, flailed, and pouted again, but to no avail. They had STATISTICS, and a marketing person with stats is as immovable as a large stone and just as smart.

Anyway, I’m sure this is much more than you wanted to know, but in the event that you would like more D.o.a.P. (or Dope, as I call it) info, don’t hesitate. And if you or one of your fellow bloggers actually READS the book, I’d love to know whether it was enjoyed or if it induced sleep…

mit freundlichen Grüßen,

John Browner

The Munich Readery

Largest English-language Secondhand-book Shop in Germany

Augustenstr. 104

80798 München

49 (0)89/121 92 403

www.readery.de

« Previous Page

* Clampdown (London: Macmillan, 1971, hc) [England]

* Clampdown (London: Macmillan, 1971, hc) [England]