September 2007

Monthly Archive

Thu 13 Sep 2007

This is the second in a series of checklists compiled by Victor Berch of turn-of-last-century authors whose careers consisted largely of novelizing plays having varying degrees of criminous content. The first was Helen Burrell Gibson D’Apery, 1842-1915, who wrote as Olive Harper.

The author of interest this time around is Grace Miller White, 1868-1957, who wrote an even longer list of such novelizations, as you’ll see in a moment, all within the very narrow time frame of 1901 to 1907.

After 1907 either the market for such novelizations began to dry up or (equally possible) a severe case of fatigue on Ms. White’s part had set in. According to Al Hubin, she wrote four additional novels worthy of inclusion in his bibliography, Crime Fiction IV, as follows. (The dashes indicate marginal crime content.)

-From the Valley of the Missing (n.) Watt 1911

-When Tragedy Grins (n.) Watt 1912 [Paris]

-The Ghost of Glen George (n.) Macaulay 1925

The Square Mark [with H. L. Deakin] (n.) Dutton 1930 [Academia]

At the moment, I know nothing more about Grace Miller White’s life. For a short account of the practice of novelizing plays, the introduction to Olive Harper’s entry will have to do for now. (Follow the link above.)

In the checklist that follows, no dashes are included. By the time this information is incorporated into the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, such indications of lesser crime content will have been determined and included.

THE MYSTERY NOVELIZATIONS OF GRACE MILLER WHITE

by Victor A. Berch

Alone in the World (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Owen Davis

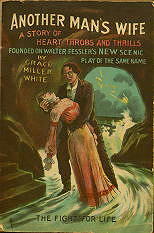

Another Man’s Wife; or, The Life That Kills (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of 4 act play The Life That Kills, by Walter [W.] Fessler

Because She Loved (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by John Reinhart

Broadway After Dark (Ogilvie,1907, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by John Oliver, pseud. of Owen Davis. Silent film: Warner Bros., 1924 (adapt.: Douglas Doty; dir.: Monte Bell)

A Child of the Slums (Ogilvie,1904. pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by W Howell Poole and Henry Belmar

The Child Wife (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Charles A[lonzo] Taylor or Hal Reid

The Confessions of a Wife (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Owen Davis

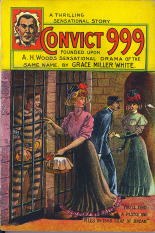

Convict 999 (Ogilvie,1907, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by John Oliver, pseud. of Owen Davis

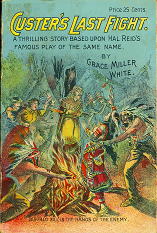

Custer’s Last Fight (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by [James] Hal[leck] Reid. Also contains two Sherlock Holmes stories by A. Conan Doyle.

Dangers of a Working Girl (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Martin Hurley, pseud of Owen Davis. Originally titled Dealers in White Women.

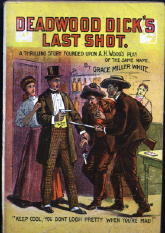

Deadwood Dick’s Last Shot (Ogilvie,1907, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Owen Davis

Deserted at the Altar (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Pierce Kingsley

Driven from Home (Ogilvie,1903, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Arnold Wolford (?) and Owen Davis

Edna, the Pretty Typewriter (Ogilvie,1907, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by John Oliver, pseud of Owen Davis

Fallen by the Wayside; or, A Chorus Girl’s Luck (Ogilvie,1907, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by John Oliver, pseud. of Owen Davis. Originally titled A Chorus Girl’s Luck in New York

Fast Life in New York (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Theodore Kremer

From Rags to Riches (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Charles A[lonzo] Taylor

From Tramp to Millionaire (Ogilvie,1906, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Owen Davis. Originally titled The Power of Money; or, In the Clutches of the Trust

The Great Express Robbery (Ogilvie,1907, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Owen Davis

Her Mad Marriage (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Frank [Charles] Allen

The Holy City (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Clarence Bennett

The House of Mystery (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by [Arthur] Langdon McCormick. Originally titled The House of Mystery and the Black Five

How Hearts Are Broken (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by [Arthur] Langdon McCormick

Human Hearts (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by [James] Hal[leck] Reid. Originally titled Human Hearts; or, Logan’s Luck

Lights of Home (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Lottie Blair Parker

Lured from Home (Ogilvie,1906, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by [James] Hal[leck] Reid

A Marked Woman (Ogilvie,1907, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Owen Davis. Silent film: World Film Corp., 1914; (scw: Owen Davis; dir.: O. A. C. Lund) [China]

A Midnight Marriage (Ogilvie,1903, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Walter [W.] Fessler

Nellie, the Beautiful Cloak Model (Ogilvie,1906, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Owen Davis. Silent film: Goldwyn Pictures, 1924 (adapt. H. H. Van Loan; dir.: Emmett Flynn)

No Wedding Bells for Her (Ogilvie,1903, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Theodore Kremer

The Peddler (Ogilvie,1903, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by [James] Hal[leck] Reid

A Prisoner of War (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Theodore Kremer.

The Queen of the Cowboys (Ogilvie,1907, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Joseph B[yron] Totten

Queen of the White Slaves (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 5 acts by Arthur J[ohn] Lamb

A Race Across the Continent (Ogilvie,1907, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by John Oliver, pseud. of Owen Davis

Rachel Goldstein (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Theodore Kremer

A Ragged Hero (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Maurice J. Fielding

A Royal Slave (Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Clarence Bennett

Ruled Off the Turf (Ogilvie,1906, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by John Oliver, pseud. of Owen Davis

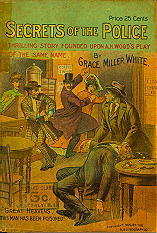

Secrets of the Police (Ogilvie,1906, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Owen Davis and Arthur J[ohn] Lamb [Paris, London, New York City]

Shadows of a Great City (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Livingston Robert Shewell

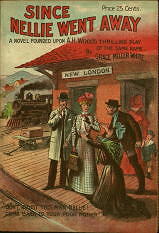

Since Nellie Went Away (Ogilvie,1907, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Owen Davis

Sky Farm (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Edward E. Kidder

The Street Singer (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by [James] Hal[leck] Reid

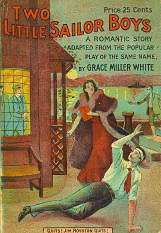

Two Little Sailor Boys (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Walter Howard

Under the North Star (Ogilvie,1906, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Clarence Bennett

The Vacant Chair (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Joseph B[yron] Totten

The Warning Bell (Ogilvie,1906, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts

Way Back in ’61(Ogilvie,1905, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Clarence Bennett

Wedded, But No Wife (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Maurice J. Fielding and Conninghame Price

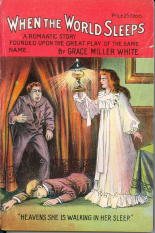

When the World Sleeps (Ogilvie,1906, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by [Arthur] Langdon McCormick and Lawrence Marston

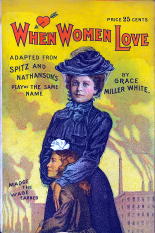

When Women Love (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by Abraham A. Spitz

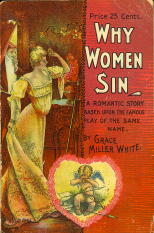

Why Women Sin (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by William C. Murphy. Silent film: Wistaria Productions, 1920 (scw:Lloyd Lonergan; dir.: Burton King) [New Jersey]

A Wife’s Secret (Ogilvie,1904, pb) Novelization of play in 4 acts by [James] Hal[leck] Reid

Wed 12 Sep 2007

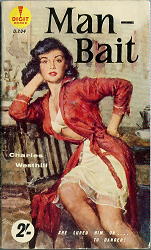

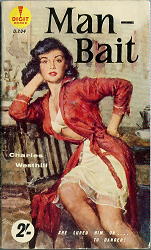

To tell you the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, I don’t know how complete this entry actually is. The one book I own by Charles Westhill is not known to either Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, nor to www.bookfinder.com, the search engine that searches all of the various online venues where books are offered for sale. If you were to Google the title, you might still pick up the eBay dealer I purchased it from not too long ago, and nothing else.

If the book I have by this author is unknown to anyone but me, how many others by him might there be, as yet undiscovered and equally unknown?

An upcoming entry to the ongoing online Addenda CFIV will look like this, slightly expanded:

WESTHILL, CHARLES

Man-Bait. Digit (Brown-Watson) D.204, UK, pb, 1958. Setting: London.

From the front cover:

“She lured him on … to danger!”

Story synopsis, from the back cover:

“Here we have a most unusual and startling novel by a new author to this series. We learn how the hero, trying to solve the bizarre mystery of his uncle’s death, and of his own strange inheritance, came face-to-face with a number of attractive women.

“One of these, in particular, tried several times to lure him to his death .. and the result of her scheming presents a most interesting climax to this absorbing book …”

Not so very helpful, right? A rather low-key approach, I’d say, in spite of rather lurid cover. Let’s open the book and try

The first few paragraphs:

I read about the murder in the morning paper. At the first glance it meant nothing at all to me. I put the paper down, and cooked my own breakfast.

That was normal procedure. I am Mark Barson, and I don’t make enough money to hire a staff of servants. I look after myself, except for an old lady who comes in to clean my Elstree flat.

I’d a hangover that morning. I’d run into a rogue by the name of Arty Crumbles the night before, and Arty could certainly put the drinks away …

Barson, as it turns out, is the author of Murder in the Morgue, fiction or non-fiction, it is not clear. Later on, still on the first page, he says:

[…] Actually I was wondering if I could hook a part in a picture that was being planned. I do all kinds of things; but I did not want to talk about myself …

The tale Arty had told Mark Barson the night before was about a recent Exhibition Hall robbery in which the haul was worth over a million pounds. The one item the thieves really wanted was a white elephant made of ivory, reportedly with a map to a buried treasure hidden inside.

Mark recalls to himself an uncle whom he’d never seen and a story about a white elephant and a treasure his family had been interested in years before. Now, on the morning after, the murder he’d read about in line one? It was his uncle who’d been killed.

Are these enough clues to know where the story is going? You may take it from here.

[UPDATE] Al Hubin says: “The book is in the British Library, but with no author date. And there’s no Charles Westhill listed in freebmd, which makes me wonder if it’s not a pseudonym.”

My reply: It’s more than likely you’re right. The book is copyright by Brown & Watson, the publisher, which is almost always a dead giveaway.

Tue 11 Sep 2007

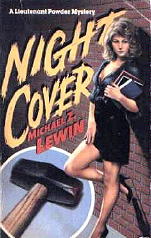

MICHAEL Z. LEWIN – Night Cover

Detective Book Club; reprint hardcover, three-in-one edition. First edition hardcover: Alfred A. Knopf, 1976. Paperback reprints: Berkley, January 1980; Perennial Library, 1984; Foul Play Press, September 1995.

For those who are interested, there is a slew of information about Michael Z. Lewin on his website, located at www.michaelzlewin.com. The first of his novels that I remember reading was one of the first three cases tackled by his private eye character, Albert Samson. I enjoyed them, and maybe I read all three, but the particulars? Right now, I couldn’t tell you.

Ask the Right Question. Putnam, 1971.

The Way We Die Now. Putnam, 1973. [Note: My review appears in the preceding post.]

The Enemies Within. Knopf, 1974

A gap of few years was filled in by the book I just read (1976), followed by five other Samson novels, with a hiatus of 13 years between the last two:

The Silent Salesman. Knopf, 1978.

Missing Woman. Knopf, 1981.

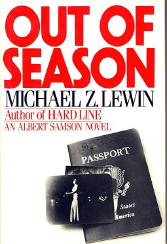

Out of Season. Morrow, 1984.

Called by a Panther. Mysterious Press, 1991.

Eye Opener. Five Star, 2004.

As for the aforementioned book in hand, it’s the first title in Lewin’s Lt. Roy (Leroy) Powder series:

Night Cover. Knopf, 1976.

Hard Line. Morrow, 1982.

Late Payments. Morrow, 1986.

In addition to his own series, however, Samson also makes a small but significant appearance in Night Cover. Al Hubin, in Crime Fiction IV, does not mention Samson as having any role in the other two books, so with no first-hand knowledge of my own, it may be safe to assume that he does not.

But on the other hand, maybe not. Not only does (Mrs.) Adele Buffington, a probation officer, appear in Night Cover, but she has a solo adventure of her own:

And Baby Will Fall. Morrow, 1988.

And not only that, a description I found of this book suggests that in it Adele is Samson’s girl friend, which puts a totally different light on something I was going to mention when I got to the review itself. Now that I think about it, I will anyway, but in any case, some further investigation is going to be needed. What I would like to know is simple. Which series characters are in which books? [See the UPDATE below.]

All three are in Night Cover, that much I do know, but there is no doubt that this is Powder’s book. He’s the lieutenant in charge of the Indianapolis police squad’s night squad (Homicide and Robbery), and I confess that I had him pegged wrong from the start. Powder is loud and obnoxious, his private life is a mess (married but not divorced), bullies his subordinates with exactitude, and only occasionally does he allow a hint of solicitude to creep in. Tough love? Maybe. As for civilians, watch out. They’re on their own when they deal with him.

I also pictured him as somewhat obese, with a sagging belly, caused by too many doughnuts from being out on the streets on too many cases on too many nights.

And yet. He’s fit enough to be attracted to the aforementioned Adele Buffington, the probation officer for the missing teen-aged girl that Powder is (in desultory fashion) looking for. And (more importantly) she to him.

You can credit author Michael Z. Lewin for this. Looking back over the first couple of chapters, I can find no reference to Powder’s outward appearance. We learn about him only through what he says and what he does. Which is plenty. Up close and personal – but no physical description.

In this book he meets private eye Albert Samson for the first time, and they definitely do not get along. If – and this is a big if – if Adele is Samson’s girl friend at the time – it is not so revealed, so I could easily be way out on a limb here, even in bringing it up – it puts a completely different slant on their later interactions, Samson, Powder and Adele. A twist in the plot that only those in the know would know about, if indeed there is anything to know.

But surely I digress. When a Mao-quoting teen-aged boy comes in with a complaint about his teacher and his (questionable) grading policies, Powder indulges him (surprisingly) for a while. When the boy mentions a girl he knows who seems to have disappeared, Powder asks around and shunts him off to Samson.

As a police procedural, which is what Night Cover is, there are a small multitude of other cases to be investigated and solved. Powder’s intuition on cases far exceeds those who work under him, to his great disappointment and frustration. Besides the missing girl, a sequence of murders suggests a copy-cat killer at work, requiring a vigorous search through back records to uncover patterns before the culprit(s) is/are nabbed.

There are parts of this tale which are amusing, if not at times laugh-out-loud funny. Lewin has a knack for understated humor, a wry look at the world that you should experience for yourself. But there’s a serious side of the story as well. As Powder’s life story becomes more and more clear, he finds himself looking at himself and his career with a greater intensity than he ever has before.

Being able to keep track of series characters in their daily life as they go from book to book is rather common in mystery fiction published today. Watching one change before one’s eyes from the beginning of one book to the end is not so common, neither now nor thirty years ago, when this book was first written.

[UPDATE] November 2005. I forwarded the review to Mr. Lewin, and received the following replies, interrupted by a question from me:

“Thanks for letting me know about the review you did of Night Cover, and for paying attention to such a venerable volume.

“As for your questions, Powder was not in the first three Samson books, but he has appeared in the five later Samson books including the current one, Eye Opener (Five Star, 2004).

“Adele appeared in Samson’s first seven novels as his woman friend – so she was in her relationship with Samson during Night Cover. I doubt I mentioned it. That was her issue and the book was Powder’s.

“In the new book Adele appears, but she is no longer Samson’s amour. She also had her own book, And Baby Will Fall (Child Proof in the UK). I think Samson was in that; Powder may have been mentioned.

“The subsequent Powder novels have included Samson but not, as far as I recall, Adele. Powder has also appeared in another Indianapolis novel, Underdog (Mysterious Press, 1993), and two short stories published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine – “Night Shift” and “911.” The latter was earlier this year.

“Mind you, I haven’t exactly read the books lately, so if I’ve gotten details wrong here and there, I won’t faint.”

Steve: Not identifying Adele Buffington as being involved with Samson at the same time she had her brief affair with Powder is what you call “her issue” and what I considered considerable constraint on your part. Other authors may have made quite a to-do about it, intensifying the relationship between the three of them immensely, but in very usual ways.

“As I said earlier, Adele was Samson’s woman friend from the beginning and through the first seven novels. Your concern is that she got close to Powder briefly. Well, Samson might have been upset, at least for a while, if he’d ever known about it, but she would never have told him, and neither would Powder. Adele’s subsequent relationship with and affection for Samson was unchanged; how she handled it or justified it was her business.

“I might have gone into that more if I’d ever written more books about her but, for various reasons, that didn’t happen and is unlikely to happen now. Depending, of course, on the size of the check you’re offering me to write them. I think it would have to be pretty large…”

Mon 10 Sep 2007

MICHAEL Z. LEWIN – The Way We Die Now.

Putnam’s, hardcover, 1973. Paperback reprints: Berkley, 1979; Harper Perennial, 1984; Mysterious Press, June 1991.

Albert Samson is a rather sensitive soul to be a private detective. Not only that, but the only reason that he gets this case is because he’s the cheapest one listed in the Indianapolis telephone directory.

No wisecracks, please. The key word here is “sensitive”, not “cheap,” and Indianapolis has enough crimes and other divorce work to keep more than a couple of private eyes on the street. This isn’t a divorce case, however. A troubled Viet Nam veteran with a history of psychiatric treatment is in jail, accused of murder. Samson, hired in quiet desperation by the man’s wife, has only one question: With his past record, why was this innocent Childe Ralph hired as an armed guard?

I liked the homey Midwestern atmosphere, and I liked Albert Samson. However, it seems only fair to point out that his slow, casual approach to the investigation can be awfully frustrating to a reader who has a lot of unanswered questions. Still, it’s the police who are guilty of taking the simple explanation, while Samson’s appraisal of Ralph Tomanek as one of the children of the world convinces both himself and the reader very early on that the job he took as a watchman was but a part of a much broader scheme.

In short, good characters nicely scaled down to earth, in a plot stretched precariously thin. [B minus]

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 2, Mar-Apr 1979.

[UPDATE] 09-10-07. I didn’t happen to mention that this was Samson’s second case, the first being Ask the Right Question (Putnam’s, 1971), which was also Lewin’s first mystery novel. Reading through the review right now, almost thirty years later, I can’t say that the story comes back to me any more than what’s there and with no more insight than you can gather for yourself. The phrase “homey Midwestern atmosphere” evokes more feeling in me than any of the specific details. That must mean something, I’ve been telling myself, and I’m sure it does.

I’ll have more to say about the author, Michael Z. Lewin, in a review I wrote much more recently. If you don’t see it here next, it’ll show up soon.

Sun 9 Sep 2007

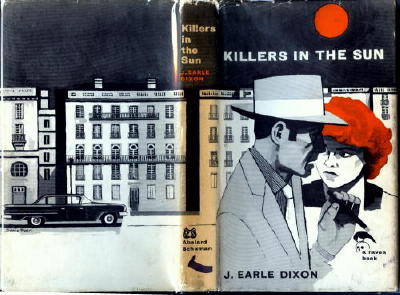

Mr. Dixon has but one title to his credit in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin. His entry, as it presently stands, is as follows:

DIXON, J. EARLE

Killers in the Sun (London: Abelard-Schuman, 1960, hc) [Spain] Abelard-Schuman (New York), 1961.

The book was published as part of Abelard-Schuman’s largely unknown and vastly under-rated “Raven Book” line of mysteries. You should be able to pick out the logo on the lower right portion of the front cover — that of a raven standing (and pecking) on a human skull.

Story synopsis, from inside the front cover:

“Spain is a country of slums, green groves, blue skies, castanets, nightingales, cats and the most beautiful women you will find anywhere. You can have your big-eyed, blue-eyed blonde. Give me the black-eyed, swarthy Spanish maid. For preference in the middle-twenties. When she has perfected her poise and sun hasn’t begun to ravage her skin. To see a lady of Spain ride in the evening, with a rose in her hair and heaven in her eyes, is something a lover of nature shouldn’t miss.

“But then I was only in their midst a little while.

“This Larrabee case which brought me to Spain kept me there a matter of thirty days. That isn’t much time in which to study a nation. But I didn’t go there as a student; my job was to save First National (Australia) being gypped for three hundred thousand pounds. Which in my currency, is twenty-five per cent over sterling and is more than I earn in a month …”

But thirty days were long enough for insurance man Dixon to involve himself in the world of the bull ring, of the glamour of the peerless bull-fighter Senorita Rosita Romero, of failed matador Martelli and the more deadly world of the luscious Faith Larrabee, of the mysterious painter Ramsey, worlds which overlapped and which provided the answer to the riddle of Clive Larrabee’s suicide in this tough, fast-moving story.

If you couldn’t quite tell, or if you really weren’t sure, telling the story is Earle Dixon himself, a brash young insurance investigator from Sydney, which in essence qualifies him as a Private Eye in almost anyone’s book. That the author and the main character are one and the same makes one wonder about the author — a pen name?

Author information, from inside the back cover:

The author of

Killers in the Sun is an Australian who made up his mind at an early age to see the rest of the world first. He has travelled since he was fifteen; has been twice round the world and, since he was twenty, has each year visited at least one “foreign” country. J.E.D. lives on the Blue Mountain ridge, near Katoomba, where exists, he says, one of the most exciting views in New South Wales.

J. Earle Dixon writes of insurance because he knows it; he began his working career with a South African insurance concern in his youth. He has been married three times but isn’t working at it now; he claims women are unpredictable and unreliable.

He has two paramount desires — to direct films and write for the Saturday Evening Post.

Unfortunately, so far as I’ve been able to discover, he hasn’t, neither one, or at least not under that name. As usual, more information, if you have it, would be welcome.

Fri 7 Sep 2007

I am always fascinated by the credited (as well as the uncredited) work of interesting genre authors for television: not, generally, that it really signifies anything very much, but there is considerable satisfaction to be drawn from recognising, or kidding oneself that one recognises, the hand of a favourite author in some otherwise unremarkable small screen work.

Rather sadly, not too many such opportunities present themselves these days.

David Goodis is an interesting case in point: while his novels and his source-as-screenplays are duly honoured in their respective quarters (read, viewed, reviewed), his admittedly slim trail of TV credits have been all but forgotten.

Thank you, Mr. Nevins, for your astute observations once again (the Bourbon Street Beat segment). (I am still indebted to you for your enlightening article ‘Cornell Woolrich on the Small Screen’ in The Armchair Detective of Spring 1984.)

The earliest Goodis television credit that I’ve been able to unearth belongs to the live anthology series Sure As Fate (CBS, 1950-51), which staged ‘Nightfall’ in September 1950, adapted by Max Ehrlich and directed by Yul Brynner in his days as a studio director with CBS-TV. John McQuade featured as the young artist on the lam from both gangsters and police. A version of ‘Nightfall’ was also presented by (Westinghouse) Studio One in the following year (July 1951).

Edmond O’Brien and Maria Riva featured in ‘Ceylon Treasure’, adapted by Irwin Lewis from a Goodis story for Lux Video Theatre in January 1952. This was a Far East adventure yarn in which treasure hunter O’Brien tries to keep safe a fabulous sapphire against the larcenous efforts of Riva and her cohorts. Adapted from the 1953 short story “The Blue Sweetheart”, I believe.

In January 1956, Lux presented their version of Warner’s 1947 The Unfaithful, featuring Jan Sterling and Hugh Beaumont in a noirish tale of murder and infidelity. Benjamin Simcoe adapted the Goodis-James Gunn story and screenplay for the hour-long play.

The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (CBS/NBC, 1962-65) was one of the most effective chiller-suspense anthologies of its period, and it seems fitting that Goodis developed for the series the teleplay ‘An Out for Oscar’ from Henry Kane’s story My Darlin’ Evangeline (Dell, 1961). Telecast in April 1963, the multi-twist story has Larry Storch’s bank clerk being set up as the fall guy by his unfaithful wife (Linda Christian) and her killer boyfriend (Henry Silva) in a turnaround heist thriller.

An anthology package of more recent years, the superbly dark and diverting Fallen Angels (Showtime, 1993; 1995), presented the 1953 Goodis short story ‘The Professional Man’ (1995), with Brendan Fraser as a hit man with a conscience. Teleplay veteran Howard Rodman (Naked City, Harry-O) adapted the half-hour episode for director Steven Soderbergh.

By happy coincidence, another favourite from the past, W.R. Burnett, whose novel Dr. Socrates has recently been revived by O’Bryan House. It may therefore be of interest to overview the TV work of Burnett, another original whose credits cropped up on the small screen, albeit intermittently, between 1950 and 1967, but whose name as screen value seems now to have faded from view.

Following adaptations of his works, by others, for the anthology series Danger (with ‘Dressing Up’ in October 1950) and Studio One (‘Little Man, Big World’ in October 1952, from teleplay by Reginald Rose), Burnett supplied two notable teleplays for episodic series in 1960. The first was ‘The Big Squeeze’ (February 1960; co-scripted with Robert C. Dennis from Dennis’s story) for The Untouchables, an exciting hour with Dan O’Herlihy as a bank robbery mastermind (of almost Dillinger dimensions) capable of outwitting Robert Stack’s Eliot Ness at almost every turn.

The second teleplay, ‘Debt of Honor’ (November 1960) for the excellent Naked City series, was a moody, sensitive piece about gambler Steve Cochran repaying an old debt to a man in Italy by marrying the man’s daughter so that she can enter the U.S.

The following work was skipped from the above chronology because, while sharing Mr. Nevins’s dread of the Warner Brothers TV ‘sausage factory’ of the day, one still wonders what was made of the race-track thriller ‘Thanks for Tomorrow’ (October 1959) for 77 Sunset Strip. With a teleplay adapted by William L. Stuart — whose own 1948 Night Cry was turned into the memorable Where the Sidewalk Ends in 1950 by Preminger — from (and I’m not certain here) Burnett’s Tomorrow’s Another Day (1946), there just may be a little of something left to savor.

In 1961, MGM used the title of their 1950 Burnett/John Huston movie, The Asphalt Jungle, for a short-lived police detective series which, while fairly interesting in itself, bore absolutely no relation to the taut caper feature. Burnett was credited (with Paul Monash) for the screenplay of the European-released ‘feature’, The Lawbreakers (1961), an extended version of the series’ second episode (‘The Lady and the Lawyer’).

His non-crime genre work for television included John Ford’s 1955 baseball drama ‘Rookie of the Year’ (story only) for Screen Directors Playhouse, ‘Manhunt’ (1965) for The Legend of Jesse James, ‘The Hellcats’ (1967), a pilot episode co-scripted with Tony Barrett about barnstorming flyers in the 1920s, and ‘The Fortress’ (1967) episode of The Virginian series (co-story with Sy Salkowitz), focusing on a Canadian border manhunt.

Earlier talents and their moments of television (and cinema) remain, unfortunately, much in need of discovery.

Thu 6 Sep 2007

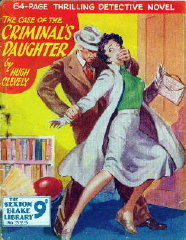

HUGH CLEVELY – The Case of the Criminal’s Daughter

Sexton Blake Library #323; The Amalgamated Press. Paperback. No date given.

As it says, this slim (if not flimsy) 64-page digest-sized paperback comes with no bibliographic information, but luckily for those with Internet access, help is just a few keystrokes away. There is a website devoted to all things Sexton Blakian, and where the link will take you, you will discover that this is #323 of the Third Series of the Sexton Blake Library. The stories appeared monthly; this is the one that came out in November, 1954. And the illustrator responsible for the cover art was none other than Reginald (Heade) Webb.

This being only the first Sexton Blake novel I’ve read in some 20 years, and the second overall, there’s no way I will talk in any general way about the character, nor should I, except to say that he, Sexton Blake, appeared as a character in over 3000 stories written by some 200 authors over a period of well over a century.

As for Hugh Clevely, well, first of all, he was one of the 200 authors who wrote stories about Sexton Blake, but of course you knew that, or you should have. According to Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, however, he only wrote 10 other Sexton Blakes, at least in novel form. His overall writing career spanned the years from 1928 to 1955 and includes a list of 35 novels under his own name, one co-written with Edgar Jepson. Only four of these novels have been published in the US.

As Tod Claymore, he wrote another eight mysteries, all with a series character named Tod Claymore. According to W. O. G. Lofts and Derek Adley’s website The Crime Fighters, “He [Claymore] had been a Wimbledon tennis player and a wing commander during the war, then switched to writing, with detection as a hobby.” Some of these books were imported or published in this country as Penguin paperbacks, the green ones.

Returning to the books Clevely wrote under his own name, the series characters that appeared in them were Chief Inspector Williams, Maxwell Archer, J. D. Peters, and John Martinson. According to a New York Times review of a film based on one of the Maxwell Archer books, the latter was a “famed fictional private detective whose greatest pleasure in life is to second guess Scotland Yard…” The occupations of the other series characters remain either unknown or quite guessable.

So Clevely was an experienced mystery writer when he started doing the Sexton Blake books, which were all written toward the end of his career. All eleven of them appeared in the four-year period from1952 to 1955. Does the experience show? It does and as the saying goes, it doesn’t.

The plot of the case in point, that is to say the book in hand, is a complicated one, and the pace is a lively one, but there’s a considerable amount of what is generically called sloppiness in the details, making you wonder if it were written too fast for a market that didn’t offer very much in compensation.

The criminal in the title is a circus performer (billed as The Great Costello) who once spent some time in jail, but who now is worth a considerable amount of legitimate money. His brother is a ne’er-do-well who is currently in a jam with some British style hoodlums. Add in the fact that Pat Costello, the acrobat, does not know he has an American daughter, but after his death by misadventure – deliberate – the fact of her existence – and that she is on a schoolgirls’ trip in Europe – means a lot to everyone who’s involved. There is also a not-so-small matter of some missing diamonds, and there (without going into further details) you have the basis for a decent if not overly rousing mystery for private enquiry agent Sexton Blake, his assistant Tinker, and Inspector Fosdyke to solve.

The details that the author works into the story, a rather pulp-like yarn, help to make the story more of a something than it is, along with a few twists in the tale that I frankly didn’t see coming. It was more than enough for me to start searching out more of the entries in Sexton Blake’s long history, but –

– some of the details don’t fit, or they clash with other ones. The conversation that Blake has with newspaper journalist Peter Grayson on page 26, for example, makes it seem that he had never heard of the girl Josie Benson before, whereas on page 23 the same two gentleman had a long conversation about the very same girl, and what Grayson should do to contrive to meet her. On page 53 Grayson and the girl are being held captive in a Martello Tower, he in a handcuff that severely restricts his range of motion – yes, that’s the kind of thriller this is – but the handcuff is never mentioned again, nor is there any restriction on his range of motion, when it comes time to attempt an escape.

And yes, of course, such a point in time does come, and not too soon at that.

— May 2006

GILBERT CHESTER – The Man Who Wouldn’t Quit.

Sexton Blake Library #74; Amalgamated Press. Paperback. No date stated.

Once again the Sexton Blake website comes galloping to the rescue. This is #74 of the Third Series, published in June, 1944. The date being in the midst of World War II, and by some reckoning among the darkest days of the war, I wondered how scarce this book (thin, digest-sized, but 100 pages long) might be. I was right. There are no other copies to be found anywhere on the Internet, and while I do apologize, mine’s not for sale.

Gilbert Chester was the pseudonym of one H. H. Clifford Gibbons (1888-1958), whose total criminous output totaled approximately 100 novels, all but a handful of them Sexton Blakes, either anonymously or under his pen name, beginning in 1923 and continuing on through 1949.

And if I knew more, I’d tell you, but I don’t, so I’ll get right to the story this time. And what a great first chapter this story has! It’s one that’s designed to grab the reader right in from the start, or maybe I’m just a sucker for stories taking place on trains, beginning with a frightened girl who enters Fenton’s compartment just as the train is leaving the station. She hurriedly tells him that she’s going to bale out before the next stop and furthermore requests that if he’s ever asked, he should say that never saw her.

From page 4:

“Forget you’ve ever seen me.”

“I’m not the type to quit, I assure you.”

“Then you’re asking for trouble, sure enough. Well, are you going to play up?”

She jumps, and so (without much hesitation) does he. And of course he has no idea where they are or into what kind of trouble he’s leapt into.

Chapter Two can hardly compete with this, but it nearly does. Dropped off by the mysterious girl at Professor Barton’s home (where he had been heading) after a short hike and a longish drive in the dark, Fenton (a research scientist) is surprised to find himself in the morning a prisoner, with another young girl holding the key to his cell-like room.

Chapter Three. We have nearly forgotten about Sexton Blake by this time, speaking collectively for myself alone, but the author hadn’t. Another young lady calls on Blake to solve a problem for her – her bungalow is being tampered with. Someone has been entering and prowling about while she is away. By an invisible man, she claims. No one has seen anyone enter or leave.

It seems like a minor problem, but Blake takes the case, thinking her recitation too theatrical and wondering what could be behind such a fanciful tale. And of course, there is a surprise in store, and not only to Sexton Blake. On page 22 they discover a body in her locked and sealed home, riddled with lead – the body, that is.

If some care had been taken, this could have been quite a mystery to unravel, but Blake makes it look easy. With only a cursory examination, Blake suggests a solution – and a rather ingenious one – to Inspector Briggan after he shows up, and of course Blake’s right and I have no idea how he did it. But it certainly is ingenious.

In any case, no more details from me. You will have a find a copy of this book for yourself, if you’d like to know more. Suffice it to say that the opening three chapters are the best, but Chester certainly makes a more than competent story out of the rest of it.

Some additional comments, though: Chapter Six is a long, ten-page conversation between two of the characters (already alluded to) which manages to both be informative and entertaining and moves the plot along while at the same time not being a mere recitation of topics and events that each of the two participants already know. It’s a neat trick, if you (as an author) can do it. Try it sometime and see.

The weakest links in the chain of the narrative are (I sadly acknowledge) Sexton Blake’s own deductions, which consist almost entirely of whole cloth and gauze and mirrors, which is (I also admit) one heck of a way to run a railroad, um, detective novel. The gaps could have been fixed, but it is entirely to Mr. Chester’s credit that the story is still is as enjoyable as it is, even if they weren’t, and they never will be.

Wed 5 Sep 2007

Apparently it’s been common knowledge to Sexton Blake fans and collectors for some time now, but I didn’t know it until yesterday, and I don’t think that most Gold Medal collectors in this country do either.

What seems to have happened back in 1956 or 1957 is that three Gold Medal books were published by Amalgamated Press, the folks who published the Sexton Blake books at the time, and had them rewritten to become, you guessed it, adventures of Sexton Blake instead.

For the full story, you can go here, but here’s a brief recap. The three Gold Medal books were the following:

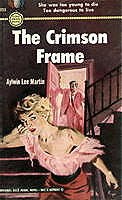

The Crimson Frame, by Aylwin Lee Martin, Gold Medal 253, pbo, August 1952.

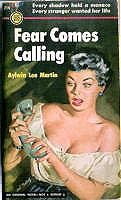

Fear Comes Calling, by Aylwin Lee Martin, Gold Medal 214, pbo, 1952.

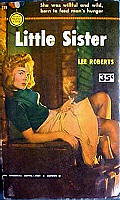

Little Sister, by Lee Roberts (Robert Martin), Gold Medal 229, pbo, March 1952. (The cover shown is that of the Canadian printing.)

A fellow named Arthur Maclean was the chap who was asked to do the conversion, which was not a very easy job, as he describes it. (“Maclean” was actually a writer named George Paul Mann, which is another tale altogether, one told in the comments in this earlier post. But I digress.) Changing the hero’s name was the least of it. Locales had to changed, Blake’s assistant Tinker had to be written in, and if Amalgamated thought they were saving either time or money, they were sadly mistaken, and they never tried such a short cut again.

For the record, also included in Part 18 of the online Addenda for the Revised Crime Fiction IV, here are the adventures of Sexton Blake that each of the above were transformed into:

The Crimson Frame ==> Deadline for Danger, by Arthur Maclean (George Paul Mann), 4th series #380, April 1957.

Fear Comes Calling ==> Roadhouse Girl, by Desmond Reid (George Paul Mann), 4th series #386, July 1957.

Little Sister ==> Victim Unknown, by Desmond Reid (George Paul Mann), 4th series, #384, June 1957.

Collectors of hard-boiled Gold Medal paperbacks who think they have them all may have another think coming. For them and everyone else, for that matter, tracking down copies of each of two versions and comparing them might provide a thesis for someone – or who knows? – a doctoral dissertation. (Probably not, but I’ll leave the suggestion on the table for anyone who wants it.)

Tue 4 Sep 2007

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Late August was a disaster for mystery writers and lovers. First we lost Magdalen Nabb, then John Gardner, then one who was a dear friend of mine. Joe L. Hensley � private attorney, member of the Indiana legislature, prosecutor, judge, dealer in rare coins and paper money, writer of science fiction since the early 1950s and more recently of 20-odd mystery novels � died on August 27 at age 81.

For the past several decades his home was Madison, Indiana, a charming town on the Ohio River just across from Kentucky and about 300 miles from St. Louis. Whenever I was driving east he’d invite me to stay over for drinks, dinner, dialogue and the use of his guest bedroom. How he could tell stories! Hoosier politics, the judiciary, colleagues in the SF and mystery fields ranging from Harlan Ellison to Avram Davidson to John D. MacDonald, encounters over the years with everyone from Robert Frost to Bob Hope — the anecdotes poured out of him like the water over Niagara Falls, especially when we’d drive together from Madison to the annual Pulpcon in Dayton, Ohio, where he was guest of honor one year and I the next.

I reviewed several of his novels for St. Louis newspapers and wrote the entry on him for the reference book that used to be called 20th Century Crime and Mystery Writers and is now for obvious reasons known as the St. James Guide to Crime and Mystery Writers. His final novel, Snowbird’s Walk, will be published early next year. Driving east will never again be so pleasant for me.

The Indiana towns I know best are Madison, thanks to Joe, and Bloomington, thanks to Indiana University’s Lilly Library where Anthony Boucher’s papers are archived. On a visit to the Lilly several years ago I came upon Boucher’s correspondence with Cornell Woolrich and his comments on various Woolrich stories. Someday I hope to include this material in an updated edition of First You Dream, Then You Die, but this column offers a fine venue for a sneak preview.

In Tony’s first letter to the master of suspense, dating from the late spring of 1944, he asked permission to reprint a Woolrich tale in his anthology Great American Detective Stories (World, 1945). Replying on June 5, Woolrich recommended that Boucher use “Endicott’s Girl” (Detective Fiction Weekly, February 19, 1938), which he called “my favorite among all the stories I’ve ever written.”

Boucher didn�t care for that one, as he explained in a July 19 letter to World editor William Targ: �It has in extreme measure the frequent Woolrich flaw � a fine emotional story which ends with loose ends all over the place and nothing really explained.� Instead Boucher opted for �Finger of Doom� (Detective Fiction Weekly, June 22, 1940), which he retitled �I Won�t Take a Minute.� �Endicott�s Girl� remained uncollected until I put it in Night and Fear (2004).

More gems from the Boucher-Woolrich correspondence are likely to pop up in future columns.

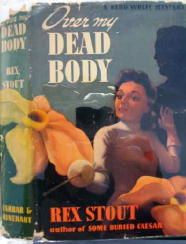

The first murder in Rex Stout�s Over My Dead Body (1940) takes place in a fencing academy. The weapon is a col de mort, a doohickey that when slipped over the usually blunt end of an epee turns it into a lethal weapon. Whether Stout made up this device out of whole cloth (if I may coin an Avalloneism) or whether it exists in the real world I have no idea and couldn�t care less. What intrigues me is whether among the readers of this Nero Wolfe adventure might have been one J.K. Rowling. Is it coincidence that the king toad of the Harry Potter books is named Lord Voldemort?

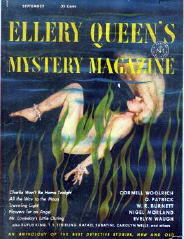

Vincent Cornier (1898-1976) was an English author of French descent who inherited a neat pile of money as a young man and thereafter devoted himself to writing short stories of fantasy and mystery. Very few of them were published in the U.S. until, after World War II, Fred Dannay discovered his work in old British periodicals and began reprinting occasional Cornier stories in Ellery Queen�s Mystery Magazine.

Eventually Cornier began to send Fred a few originals. Earlier this year I had occasion to re-read most of his stories from EQMM. The one I found most intriguing was the first of those originals, �O Time, In Your Flight� (September 1951).

Why? Because it contains a uniquely beautiful clue to the solution: one that is available only to readers who recognize the title�s poetic source and remember the three words in the poem that come just before the five in the title! The question all but asks itself: Was it Cornier or Fred who put that brilliant title on the story? Their correspondence, which is archived at Columbia University, doesn�t indicate what title was on the tale when Cornier submitted it, but we know that Fred had a penchant for changing the titles of many of the stories he published. Also I find no evidence in Cornier�s other stories that he had any particular interest in poetry, while Fred not only collected rare first editions of poetry but also wrote some of his own. It seems to me far more likely than not that the stroke of genius was Fred�s.

If further proof is needed, there�s indisputable evidence that Fred knew the poem in question: he used the first three words of the line, the words that provide the clue to Cornier�s story, as the title for another tale by another author that appeared in EQMM a few years later! The author was Dorothy Salisbury Davis, the issue June 1954. After you�ve read �O Time, In Your Flight� in Duels in Shadows, the forthcoming Crippen & Landru collection of Cornier�s best mysteries, Google the title and you�ll quickly find what I�ve been hinting at without, I hope, having given it away. But don�t do it before or you may spoil the story!

Tue 4 Sep 2007

Posted by Steve under

Authors[3] Comments

Before reading Heather’s essay on her grandfather, Morton Wolson, I suggest you go back and read (or re-read)

my previous post on Mort’s career as a pulp writer, including the comments, one of them left earlier by Heather.

Dear Steve,

I perused my father’s e-mail detailing my grandpa’s history concerning his pulp fiction writing. However, if you want a portrait of his personality, I can relate some interesting stories. Regrettably, Grandpa Mort believed that his pulp fiction writing wasn’t to be taken seriously, and as my father has already said, he was working on some other novels, which he deemed more important. How ironic that the writing he took for granted has now become his legacy!

Concerning his interests, grandpa was a “fellow traveler” in the Spanish Civil War, but would always quiz both my father and I repeatedly on the correct definition of Marxism. In fact, the debates that my father and Mort would get into concerning Marxist ideology, while Mort was driving, would almost plow my Grandma Gaye, Mort, my father and I into several of New York’s finest telephone poles. My grandmother would clutch me around the waist and scream, “Stop debating, oh my God, you’re going to kill us all!”

Of course, I found these predicaments highly amusing. In fact, during the McCarthy era, Mort was investigated by the FBI for having fought in Spain. He retrieved the 150 page report on himself after the Freedom of Information Act was passed, and read it aloud to all of us. Ironically, most of the report was crossed out, so we couldn’t adequately read anything. Also, prior to fighting in the Spanish Civil War, Grandpa Mort was proud to be the first individual to attempt to organize a union at Macy’s department store. Unfortunately, he was subsequently fired.

Grandpa Mort was also a staunch vegetarian. He never ate a piece of meat in his entire life! This was due to his own father’s vegetarian “phase.” However, when Mort was old enough to choose whether or not he would eat meat, my great grandfather took him through a slaughter house in order to strengthen his resolve against it. Grandpa never imposed vegetarianism on my own father, and rather encouraged him to eat meat. Grandpa’s meat substitutes were half jars of peanut butter, sandwiches piled high with cheese and lettuce, and vegi-steaks.

One of my favorite vignettes concerning Mort’s various escapades is the story of how he was a Buddhist at 20 years old. He decided to find out for himself what he was exactly dealing with. So, he hopped a freighter and questioned the chief Buddhist in Calcutta. He asked, so what is the answer to all of this? The monk replied, “I don’t know,” and grandpa, infuriated that he had traveled all the way from New York, exclaimed, “you have rocks in your head!” Later on in life, grandpa confessed to me that the monk was right and he was wrong. Mort claimed his infamous response was simply that of a brash youth. He believed the monk was actually very wise upon reflection.

When I knew Mort, he was an Atheist. He would also tout Solipsism, the theory that we are all merely products of our own five senses and that nothing which seems to exist actually does. Moreover, when I questioned him regarding his religious inclinations, he answered, “Honey, the only thing I can truly believe in is the law of nature. If you walk off of a cliff, gravity ensures that you will fall off of it, and dash out your brains.” Although this reply seems somewhat severe, I always regarded Mort’s worldly views positively, and deeply admired him. His personality was very much like a character in one of his Peter Paige detective stories.

These are some colorful pictures of different ways in which I remember Grandpa Mort. Moreover, he always encouraged me to write, write, write. As things presently stand, I am entering graduate school in order to acquire my doctorate in English Literature. Hence, I end up writing quite a bit. I hope the aforementioned descriptions aptly represent both the awe-inspiring, tough and sometimes funny character of my beloved grandpa.

« Previous Page — Next Page »