February 2008

Monthly Archive

Thu 14 Feb 2008

L A. CONFIDENTIAL. Unsold television pilot, 2003. Keifer Sutherland, Josh Hopkins, Melissa George, Pruitt Taylor Vince, Eric Roberts. Director: Eric Laneuville. Based on the novel by James Ellroy.

Filmed in 1999, says IMDB, as part of a deal with HBO in 2000 as the first installment of a 13-part mini-series. When that didn’t happen, Fox took interest, but in the end, they also turned it down. Their loss, and ours.

The date 2003, by the way, is when the cable network Trio finally aired it as part of a long marathon of similar bankrupt and cancelled projects.

I’ve not read the book, which is number three in Ellroy’s series of 1950s L.A.-based novels: The Black Dahlia was the first; number two was The Big Nowhere; and the fourth was White Jazz. I’ve also not seen the full-length movie version of L. A. Confidential (1997), a huge gap or gaffe on my part (take your pick), but at least you can say that this review of the TV version is unbiased in terms of any sort of comparisons, or any other kind of useful information.

This TV film, all that was ever made, is only 50 minutes long, and it ends with a large TO BE CONTINUED across the screen. Just as all of the pieces were coming together! Utter frustration.

Keifer Sutherland, not yet a 24-carat star, is Det.-Sgt. Jack Vincennes in this one, the role played by Kevin Spacey in the film. Melissa George is would-be movie starlet Lynn Bracken, played by Kim Basinger in the movie. I could go on and on like this, but the TV version is not the same story as the earlier version (or so I’m told), but essentially a different (and ultimately longer) adaptation of the book, produced and created by men with different ideas, limitations and goals in mind.

Basic story: Vincennes, having killed an innocent man during a drug bust gone bad, tries to make up for it by anonymously sending money to the dead man’s widow. This means that he needs more money than he makes, which means in turn that he has to go on the take. Not a good idea when Internal Affairs is watching, not to mention the editor and publisher of Hush Hush Magazine.

The TV version is visually striking in color, but in terms of overall production values, I doubt that it holds up in that regard to the movie. Note to self: watch the movie, and report back.

[UPDATE] I haven’t found any images to add to this review, but for as long as it’s there, you can watch this short pilot online in five parts, beginning with http://www.truveo.com/Part-1of-5-LA-Confidential-TV-pilot-Kiefer/id/1356656397

[UPDATE #2] 03-07-12. As suspected, the video above is no longer there. See the comments, though, for information as to how to find a copy.

Wed 13 Feb 2008

URSULA CURTISS – Catch a Killer.

Pocket 940; 1st pr., June 1953. Hardcover edition: Dodd Mead, 1951, as The Noonday Devil.

It’s my guess that every time one of Ursula Curtiss’s books is reviewed today, it begins with the observation that her mother was mystery writer Helen Reilly, and that her sister was mystery writer Mary McMullen. (And equally obviously, I’m no exception.)

It must have been in the genes, but during the time when all three were actively writing (Reilly from 1930 to 1962; Curtiss from 1948 to 1985, with a posthumous collection of short stories; and McMullen from 1951 to 1986), do you suppose that anyone ever asked them what was in the water they were drinking?

While Helen Reilly had a series detective who appeared in most of her books – Inspector McKee of Manhattan Homicide – Ursula Curtiss and Mary McMullen, from all I know, gained largely from reading about them, were heavy practitioners of (suburban?) domestic malice and/or romantic suspense, and neither of them used a repeating character in any of their books.

For me, this is largely hearsay, especially as far as Curtiss is concerned, as this is the only book of hers I’ve read. So far. In any case, what you expect is not always what you get. In Catch a Killer, for example, I was surprised (although far from nonplussed) to discover that the leading character is male, and that the story begins in Manhattan. I had the uneasy feeling that I was leaning one way, and the book, with Curtiss in charge, was going another.

In the second half of the book, the scene changes, however, and rather drastically. Under some pretext or another, all of the leading characters seem to find their way to the same small country town in New England, and when they do, everything seems to revert to normal. (By which I mean, closer to what was expected, if not anticipated.) And as a direct consequence, most probably with the characters’ closer proximity to each other, the action seems to pick up as well.

The atmosphere is black, introspective and moody throughout. And as you well know, or you should, coincidences simply thrive in such climates – beginning as they do here, in Chapter One. When you walk into an unfamiliar bar for the first time, for example, you never know whom you’ll meet, and that’s where Andrew Sentry finds a man who’d been in the same Japanese prison camp as his brother Nick – an encounter occurring solely by chance.

Nick had died in a subsequent attempt to escape, and his death, Andrew for the first time is now told, was no accident. There was an informer in the camp – someone Nick knew – who told their guards of Nick’s plans, which were then foiled. This is an unusual (if not unique) means of killing someone, but who was the mysterious man who called himself Sands? And what was his motive?

More coincidences begin to pile up. Every male in Andrew’s small circle of friends and acquaintances suddenly seems to have been a Japanese prisoner in the Philippines at some time or another during the war. Nick’s fiancée Sarah Devany may have received a postcard in code from him just before he died, but when a simple question might have unraveled the mystery before it has even begun, there are barriers which by fate have carefully been laid in the way.

When Andrew came to break the news of Nick’s death to Sarah, it is revealed, he found her kissing another man, and he has not spoken to her ever since. And since the case for murder is so flimsy, the police cannot be called in, which limits Andrew’s resources to himself and whoever he feels he can trust, the list of those in this category changing chapter by chapter.

And in similar fashion does the reader’s grip on the story, or vice versa, the story’s grip on the reader. Excellent characterizations are mixed helter-skelter with a plot that’s held together with a strong, industrial brand of duct tape. Nonetheless, New England summer towns can be filled with as much malice as large population centers such as Manhattan, and the generally capable touch of Ursula Curtiss goes a long way in proving it.

[UPDATE] 02-13-08. I read and reviewed this book four years ago, and do you think I remember it? If I hadn’t written this review, I don’t believe I would even have remembered reading it, if you’d asked me.

But after reading and slightly revising the review, it all came back to me — everything, that is, except whodunit. I’m willing to wager that if I started to read the book again now, I still wouldn’t remember who the killer was.

I don’t know whether that’s a good thing or not.

But in any case, I mentioned in the course of the review that this was the first mystery I’d read that Ursula Curtiss had written. It’s also still the only one, not through any fault of hers!

Wed 13 Feb 2008

THE LONE WOLF IN PARIS. Columbia, 1938. Francis Lederer, Frances Drake, Walter Kingsford, Leona Maricle, Albert Dekker. Director: Albert S. Rogell. Based on the character created by Louis Joseph Vance.

Michael Lanyard, also known as The Lone Wolf, appeared in eight novels written by Vance between 1914 and 1934; in 24 movies between 1917 and 1949; in a 1948 radio show on Mutual; and in a 1954-55 syndicated TV series. (I didn’t want you to think we were talking about any old fly-by-night sort of character here.)

By the end, he was essentially a good guy, almost but not quite a private eye, I believe, but he didn’t start out that way. In the beginning he was a gentleman European jewel thief, pure and simple, but his penchant for helping beautiful women in distress eventually convinced him that working for the law instead of against not only had the advantage of being able to continue his narrow-escape adventures, but without the disadvantage of always having the police close behind his heels. At least theoretically, anyway.

In The Lone Wolf in Paris, suave Czechoslovakian-born Francis Lederer’s only opportunity to play him, Lanyard is on the edge of reform. He has letters from heads of police departments from all over Europe to vouch for him, but the hapless manager of the Paris hotel where he is staying immediately has a suspect in hand when robberies begin taking place in several rooms of his establishment.

In the hotel at the same time, it seems, are three rich members of Arvonne royalty, who between them have the crown jewels of their country. (Arvonne is a small country found somewhere on the map near France, we are led to believe.) Princess Thania (Frances Drake) desperately needs them back. Once the people of Arvonne learn that they are missing – a good deed gone bad – the Queen will be forced to abdicate.

There is a lot of pleasant thievery and derring-do packing into the 66 minutes of this movie. There are also a few brief opportunities for romance between all of the switches back and forth between the real gems and fake ones made of paste. It’s a minor film, but a very enjoyable one nonetheless. The hour and change in running time goes by very quickly.

Tue 12 Feb 2008

NEXT. 2007. Nicolas Cage, Jessica Biel, Julianne Moore; Peter Falk. Director: Lee Tamahori. Based on the short story “The Golden Man,” by Philip K. Dick.

When I was growing up in the middle to late 1950s, my favorite SF author was Philip K. Dick. I was way ahead of my time, I think, because nobody I knew had ever heard of him. Then I learned of SF fandom, that would have been in the early 60s, and suddenly I wasn’t alone any more. He wasn’t everybody’s favorite author then, but in that crowd at least he was read, and his stories were talked about.

And now, ever since the movie Blade Runner, I would imagine – I’m talking now 1982 – everybody who goes to the movies and pays attention to the authors that wrote the stories that movies are made of has heard of Philip K. Dick. He had ideas – many of them solidly paranoiac and/or hallucinogenic – ideas that no one ever had then and no one seems to have now, and often questioning the meaning of reality itself. Is the world a stage, our surrounding only sets? And so on and et cetera.

The premise of Next is that its hero, an obscure and not very successful Las Vegas stage magician named Cris Johnson [Nicolas Cage], has the ability to see exactly two minutes into his future. Now you know and I know that this can’t be done, but given the premise, how might a man having such a ability deal with it? Superheroes, says Stan Lee, have great responsibilities. Is it not so?

Cris Johnson tries to hide his behind the facade of his magic act, performing before small audiences in rundown clubs. So far, up to the time the movie begins, he has succeeded. But this is a crime film, a top notch action thriller – some of it choreographed so well that I had to stop the DVD, backtrack and watch it again. [Insert a small “heh” here.] The second premise at work is that a very sophisticated gang of terrorists going to set off a nuclear bomb somewhere in the Los Angeles area.

It is difficult to know exactly what they hope to gain from this – or maybe it was explained and I missed it – but that’s OK. I have an imagination, and I can use it. It is federal agent Callie Ferriss’s job – she’s played by Julianne Moore – to convince Cris Johnson to use his ability to save the lives of eight million people. Cris Johnson is sympathetic, of course, but he knows that once he does, his life as he knows it is gone forever.

Not only is this an action thriller, but it is also a romantic film. Jessica Biel – oh so beautiful, and he, Nicolas Cage, such a magnificent scarecrow of a man – plays Liz Cooper, and somehow she is part of Cris’s future. He knows it, and he doesn’t know how, but of course she is… Have you seen the previews? Should I tell you? No, but keep in mind that this is also an action thriller, and she is very much a part of the action…

…as an innocent victim. I just simply have to tell you that. No one as young and innocent and beautiful as Liz Cooper is could be anything but an innocent victim in a movie.

The men who made this film did an absolutely smashing job of making the first part of it, the first two or three acts or so. It could not have been easy task in figuring out ways to make the science-fictional premise understandable to mainstream audiences, but they did.

Unfortunately premises such this one lead easily to all kinds of unanswered questions, and I will not bore you with mine, largely because I do not have answers to them. If you watch the movie, I suspect you will come up with as many of yours as I did, and there may not even be any overlap.

There is another “unfortunately” coming up here in my comments on the film, and unfortunately I am running out of wind, if not space. And this one involves the ending. All movies have to have endings. I wish this one didn’t, in one sense, and in another, I wish it didn’t have the ending it has. I have the feeling that I am not alone in feeling this way.

[LATER ON THE SAME DAY.] I have been thinking the ending over, and feeling an inch (perhaps a foot but probably not a yard) more positive about it, I think I would like to revise my comments a bit, or add to them in this fashion. If I am right, and I now believe I am, the ending of the movie is really rather clever.

I am naturally reluctant to say that I was wrong before, of course. The fact remains that for the kind of audience who would be most attracted to this movie, I am sure the ending will disappoint them greatly. Action-minded audiences do not enjoy being taken lightly.

[EVEN LATER.] I was right. After posting my comments, I went to read what some of the people on IMDB had to say. I didn’t get far. Here are three. You can go read the rest for yourselves.

“I DON’T WANT TO IMAGINE A FILM, I WANT TO WATCH IT!!!!!”

“I see 4-5 movies a month in a theater, but when Next ended tonight, it was the first time I’d ever heard a crowd ‘BOO’ a movie.”

“This is the kind of movie that doesn’t seem so bad until you find out that there are people who actually liked it.”

Mon 11 Feb 2008

Dear Steve,

I am aware of “Gun-Witch of Hoodoo Range” by Emmett McDowell [mentioned in the comments posted after my last letter to you] and even have read it. The title, supplied by Fiction House, was derived from “Gun-Witch from Wyoming” by Les Savage, Jr., in Lariat Story Magazine (11/47). Based on the underlying correspondence, Malcolm Reiss was desperate to get another Señorita Scorpion story from Savage, and this was meant as an interim attempt to keep interest in the character because Savage at the time was writing his first novel.

Savage’s first three Señorita Scorpion stories do work as a trio of interrelated stories, similar to the trios of short novels Max Brand had written for Western Story Magazine, and for this reason could be combined into a stand-along book as we did initially. After “Secret of the Santiago,” Savage no longer wanted to do more stories, and only “The Curse of Montezuma” preserved the principal characters introduced in the first three short novels. After the fourth story, Savage introduced other characters, excluded Chisos Owens as he went along, and the sixth story even has a first-person narrator who is a new character to the series. For this reason, among others, we never thought it a good idea to collect these later four stories into a single volume.

The ENCYCLOPEDIA OF FRONTIER AND WESTERN FICTION (McGraw-Hill, 1983) is the primary reason Golden West Literary Agency came into being. Bill Regier, then director of the University of Nebraska Press, in 1989 proposed that Vicki and I prepare a second edition of this reference book. We set about contacting Western writers or their estates to update our bibliographies. We also added several authors who were not included in the first edition.

T.V. Olsen, who I had known for years, urged me to include Les Savage, Jr., and lamented he had not been included in the first edition. He felt Savage was one of the most talented Western writers and deserved an entry. I read a number of Savage’s stories and agreed. I then contacted Marian R. Savage, Les’s widow, for biographical and bibliographical information. She pleaded with me to find an agent for Les’s work.

The same thing happened with L. P. Holmes’s son. Lew Holmes had died after the first edition came out and he had been most helpful with his entry. Contacting New York agents, I was amazed that no one wanted to represent a deceased author unless he had been a client while alive. In the end we had such a number of client estates that needed representation that we founded Golden West to represent them. T.V. Olsen became our first living client.

Until 1994 we still planned on doing the second edition, but Bill Regier had left Nebraska, and with the launch of the Five Star Westerns, our hardcover Western fiction series co-published by Thorndike Press, then a division of Macmillan, we no longer had the time to work on the second edition. Now it would be impossible to do it simply because there still is no time.

We edit and co-publish twenty-four new Western titles a year in the Five Star Westerns and three new Western titles in the Circle V Westerns. Some of the material we prepared for entries in the second edition has been used instead as Forewords to Five Star Westerns editions, for example that which I wrote for RANGE OF NO RETURN: A WESTERN DUO by D.B. Newton, with a Foreword by Jon Tuska. [Dec 2005].

In the end, I think this decision not to continue with the second edition was the right one. We both changed from the passive rôle of being literary historians to the active rôle of being publishers of and agents for Western fiction in the present and future.

All Savage would have had would have been a first-time entry in the second edition. Instead, we have been doing one and two new books by him every year, beginning with FIRE DANCE AT SPIDER ROCK by Les Savage, Jr. with a Foreword by T.V. Olsen [Nov 1995]. Instead of being a footnote in the literary history of the Western story in the 1940s and 1950s, Les Savage’s work is being read and enjoyed by readers who were not alive when he was, and so has won a longevity for himself that his early death would otherwise have precluded.

We have also introduced new authors to readers of Westerns and represent some of the most talented of the current generation such as Johnny D. Boggs, Stephen Overholser, and William A. Luckey. We have restored many of Zane Grey’s finest Western stories in authentic texts based on his holographic manuscripts and have several yet to go; we publish six new Max Brand titles a year (some of these also restorations), have launched publishing programs for Will Henry, Frank Bonham, Lauran Paine, Ray Hogan, T.T. Flynn, Peter Dawson, Robert J. Horton, Dane Coolidge, Lewis B. Patten, Wayne D. Overholser – the list goes on and on. Almost six hundred Western titles are sold by Golden West every year worldwide.

Mon 11 Feb 2008

WILLIAM R. COX – Death on Location. Signet S2158, paperback original; 1st printing, July 1962.

It begins with a baseball game, the championship series of the Las Vegas Strip Baseball League, which if you think about it, sounds like a lot of fun. Besides being a reformed gambler, however, Tom Kincaid is a shoestring movie producer as well, and when he moves his crew upstate to start filming an adventure epic starring his live-in girl friend, he unknowingly carries the dirt of big city dope traffic with him.

The detection is a flabby effort, to tell the truth. The solution to the murder of the leading lady’s stand-in seems to flop out of its hidey closet of its own accord, but the message is that the movie business is really just plain hard work. The logistics of making a movie are staggering, to put it mildly, and they’re put together by honest, industrious people. Under the sophistication, folks, they’re just like us. (C)

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 2, Mar-Apr 1979.

[UPDATE] 02-11-08. Cox was another paperback writer in the 1950s and 60s who began his career in the pulps, writing mysteries like this one — I’m almost positive that Tom Kincaid appeared in his short stories long before he started showing up in full-length novels — but Cox wrote a ton of westerns and sports fiction as well. Short or long, magazine or paperback, it didn’t seem to matter. The only books he wrote that appeared in hardcover, though, while he was alive, were sports stories for boys, with titles like Trouble at Second Base and Rookie in the Back Court.

When there was a lull in writing books and short stores, Cox did TV screenplays, shows like Bonanza, Wagon Train and Tales of Wells Fargo, but according to IMDB, an episode of Route 66 as well, among many others.

There were a couple of interesting characters to be found in his western paperback fiction. First was a guy called Cemetery Jones, about whom I know little more than his name, and second, although this may not count, after William Ard died, Cox wrote a bunch of the “Buchanan” books under the Jonas Ward byline.

Thanks to Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, here’s a list of all of the Tom Kincaid novels. Someone else will have to help me out on the pulp stories Kincaid appeared in. I can’t find any reference to specific titles or dates, but I’m positive I’ve read one or two of them over the years.

Hell to Pay. Signet, 1958.

Murder in Vegas. Signet, 1960.

Death on Location. Signet, 1962.

William R. Cox died in 1988, at the age of 87. Here’s a link to his obituary in the New York Times.

Sun 10 Feb 2008

Posted by Steve under

Authors[2] Comments

Remembering PHYLLIS A. WHITNEY,

by Dean James.

Phyllis A. Whitney’s books have been great favorites of mine for as long as I remember. I discovered her juvenile mysteries about the same time that I discovered her adult suspense novels, and I read both groups of books with great pleasure. Growing up on a farm in Mississippi, I did all my world-traveling in those days through books. Miss Whitney took me to far-flung, exotic places that I could never hope to go on my own, and after I read one of her books I felt I had been to those locales, if only for a brief while.

Phyllis A. Whitney’s books have been great favorites of mine for as long as I remember. I discovered her juvenile mysteries about the same time that I discovered her adult suspense novels, and I read both groups of books with great pleasure. Growing up on a farm in Mississippi, I did all my world-traveling in those days through books. Miss Whitney took me to far-flung, exotic places that I could never hope to go on my own, and after I read one of her books I felt I had been to those locales, if only for a brief while.

I found her address in a reference book, back in 1983, and I wrote her the first fan letter I ever wrote to an author. Within ten days, I received a reply. What she had to say in that letter told me that she had read my letter and thought about what I had to say, and I was touched by the time she obviously took to respond.

Later on I had the great pleasure of meeting her in person, twice. First was in 1988 at the Edgar Awards Banquet; Miss Whitney had been named Grandmaster for that year. I found my way to her table before the festivities started, clutching one of my favorite of her books (Emerald, in case anyone is curious), and rather shyly introduced myself and told her how much pleasure she had given me over the years through her books. Her face lit up, and she was obviously so delighted by talking to a reader, she charmed me completely.

I saw her again a few years later at Malice Domestic, and Dorothy Cannell (another big fan of hers) and I stood in line waiting to get books signed, happily discussing our favorites. Once again, when I had the chance to speak to her, I received that same beaming smile and obvious joy she had when talking to readers. She was over 90 by that time, and her body might have been frail, but her mind was still razor-sharp. She delighted many people that day during the panel she did at Malice.

Sometime last year I decided it was time to reread some of her work, and I was just as enthralled with it as I had been when I read the books for the first time. Despite the fact that she was (by this time) considerably older than her heroines, she had this uncanny ability to understand what hurdles young women of that particular decade were facing and write credibly about them.

She told me in her letter, back in 1983, that the reason she had stopped writing historical novels was that she was far more interested in the problems of women of the present, and I think she did it with great compassion and understanding. Emerald is a prime example of this.

Phyllis A. Whitney was a wonderful storyteller, and I will always relish the time I spent reading her books, and the times to come when I will read them again.

Sun 10 Feb 2008

After the

discussion on this blog about the two versions of Steve Fisher’s

I Wake Up Screaming, Frank Loose asked the following question in the comments section:

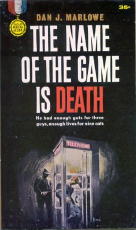

“If I understand correctly, Black Lizard did a similar thing with Dan Marlowe’s The Name of the Game is Death. I believe their edition is of a revised, tamed down version of the book, and that the original first edition was a bit more violent. Perhaps you can enlighten me on this?”

I asked around but didn’t get anything specific about this, so I asked on the rara-avis Yahoo group. Mark Sullivan posted the following response, which he’s allowed me to reprint here. NOTE the spoiler alert partway through.

I have both Gold Medal versions of The Name of the Game is Death, but I don’t have the Black Lizard version to compare them to. However, some time ago, I posted this comparison, so perhaps [from this] you can tell us which BL used:

I recently found a copy of the 1962 The Name of the Game is Death. I haven’t read it yet, but I have compared it to the copy I already had [which was] “Copyright 1962, 1972 … Printed in the United States of America, January 1962/January1973”

The story is exactly the same. The earlier one has one extra chapter, but that is only because the later edition combines Chapters VIII and IX. However, the book has been extensively rewritten, from first page to last. The language of the earlier one is a bit more clipped, more “just the facts” simple sentences, but longer paragraphs.

Here are two examples. The first two paragraphs from 1962:

“From the back seat of the Olds I could see the kid’s cotton gloves flash white on the steering wheel as he swung off Van Buren onto Central Avenue. On the right up ahead the strong late September Phoenix sunshine blazed off the bank’s white stone front till it hurt the eyes. The damn building looked as big as the purple buttes on the rim of the desert.

“Beside me Bunny chewed gum rhythmically, his hands relaxed in his lap. Up front, in three-quarter profile the kid’s face was like chalk, but he teamed the car perfectly into a tight-fitting space right in front of the bank.”

From 1973:

“From the back seat of the Olds I could see the kid’s cotton gloves flash white on the steering wheel as he swung the car from Van Buren onto Central Avenue. The strong, late-September, Phoenix sunshine blazed off the bank’s white stone front till it hurt the eyes. The damn building looked as big as the purple buttes on the rim of the desert.

“Beside me Bunny chewed gum rhythmically, his hands relaxed in his lap. Up front the kid’s face was like chalk, but he teamed the car perfectly into a tight-fitting space right in front of the bank.”

So it’s close, but subtly different.

And the last chapter, from 1962: [SPOILER ALERT]

“I was in black darkness for six months. I may have gone a little crazy, too. I gave them a hard time. I went the whole route: baths, wet packs, elbow cuffs, straitjackets, isolation. I stopped fighting them a little while ago. They don’t pay much attention to me now.

“Even before I could see again, I knew what I looked like. I could feel the reaction, when a new patient was admitted, or a new attendant came on duty. Hazel came to see me four or five times. I refused permission for her to be allowed in.

“They don’t know that I can see again, that I’m not crazy. They think I’m a robot. A vegetable.

“I’ll show them.

“I have a hermetically sealed quart jar buried in the ground up in Hillsboro, New Hampshire, and another in Grosmont, Colorado, up above the timber line. There’s nothing but money in both. I don’t need it. All I need is a gun. Some one of these days I’ll find the right attendant, and I’ll start talking to him. It will take a while to convince him, but I’ve got plenty of time.

“If I can get back to the sack buried beside Bunny’s cabin, plastic surgery will take care of most of what I look like. With a gun, I’ll get back to it.

“That’s all I need — a gun.

“I’m not staying here.

“I’ll be leaving one of these days, and the day I do they’ll never forget it.”

And from 1973:

“I was blind for six months.

“I may have gone a little crazy, too. I went the whole route: baths, wetpacks, elbow cuffs, straitjackets, isolation. I stopped fighting them a while ago. They don’t pay much attention to me now.

“I knew what I looked like even before I could see again. I could tell from the reaction when a new patient was admitted or a new attendant came on duty. Hazel came to see me five or six times. I refused to consent for her admission.

“They don’t know that I can see again. That I’m not crazy. They think I’m a robot. A vegetable.

“I’ll show them.

“There’s a hermetically sealed quart jar buried in Hillsboro, New Hampshire, and another in Grosmont, Colorado. There’s nothing but money in both. I don’t need money. All I need is a gun. One of these days I’ll find the right attendant, and I’ll start talking to him. It will take time to convince him, but I’ve got plenty of time.

“Plastic surgery will take care of most of what I look like if I can get back to the sack buried beside Bunny’s cabin. With a gun, I’ll get back to it.

“That’s all I need — a gun.

“I’m not staying here.

“I’ll be leaving before too long, and the day I do they’ll never forget it.”

Again, same content, slightly different presentation. Nothing had to be changed to make it a series. As a matter of fact, the prologue in my copy of One Endless Hour (March 1969/January 1973) begins with yet another close, but not quite the same, version of the last chapters of The Name of the Game. I don’t have the Vintage edition, so I can’t tell you which version they used, one of these or yet another one.

The individual changes that Mark mentions are interesting but essentially only stylistic. The consensus has always been that drastic changes had to have been made, in order to transform the hero into a series character. The changes demonstrated by Mark certainly don’t fall into that category.

In the meantime, Frank was also asking the question to a few other people. Here’s the reply he received from Chuck Kelly, who is very definitely an expert on Dan Marlowe’s books. He agrees with Mark in terms of the stylistic changes, all relatively minor, but then goes on and provides what appears now to be a definitive answer:

Thanks for your question on the two versions of The Name of the Game Is Death.

There are indeed two versions, both published as Fawcett Gold Medals. The original one was published in 1962, and the revised version was published in 1973. It is sometimes said that the 1973 version is a “toned-down” version, but, with a couple of exceptions, that really isn’t true. In fact, it’s basically just a rewrite with some different phrasing, paragraph structure, etc.

The significant differences in the story in the two versions, and they are rather subtle, have to do with a couple of passages in which the main character discusses his sexuality with his new girlfriend, Hazel Andrews. In the 1962 version, the character appears to be a bit more uncertain about his heterosexuality than he does in the 1973 version.

Also, in the 1962 version, there’s the implication that killing turns him on, which is removed from the 1973 version. The change probably was made to make the character fit more closely the “secret agent” Drake character readers knew by then, one who was sexually potent and a tough guy, but not a wanton killer.

The Black Lizard edition actually is a re-issue of the 1962 version, so you’ve read the story as Marlowe originally wrote it.

Sat 9 Feb 2008

CYRIL HARE – The Christmas Murder.

Mercury Mystery 190; digest paperback reprint. No date stated, but circa 1953. Original title: An English Murder. British hardcover edition: Faber & Faber, 1951; US hardcover: Little Brown & Co., 1951. Other paperback reprints: Penguin, UK, 1956, 1960; Perennial, US, 1978; Hogarth Crime, UK, 1986; House of Stratus, UK, 2001.

This is not a difficult book to find, in other words, if all you want is a copy to read. Even so, the only cover image I’ve been able to come up with is the one I discovered last week in a stack of previously unsorted digest paperbacks beside my desk. It’s a throwback to the Golden Age of Detection, in terms of plot, but the setting and general ambiance – postwar England – has the players at odds with each other for reasons not usually associated with the previously mentioned Golden Age.

Post-war England was in a stage of upheaval, with the lower classes beginning to feel that the upper classes perhaps need not always be bowed down to, and politicians on either side – and politics in general – were becoming more strident as a consequence. Clashes between various segments of society (the aristocracy vs. the radical socialists, for example) were growing more common, including (it appears) between the old, who remembered pre-war traditions, and the young, who did not. (Not to mention the young who simply wished the old would step aside, having had their day.)

Neither of Cyril Hare’s most commonly used series characters makes an appearance in this novel. Inspector Mallet was in six of the author’s nine novels. Francis Pettigrew, an elderly and somewhat embittered barrister was in five of them, with an overlap of three in which they both appeared. If this sounds like the beginning of a math problem, I apologize. (I am also not counting two collections of Hare’s short stories.)

Most of Cyril Hare’s mystery fiction, the author himself a barrister and a judge, deals with courtroom trials and/or the finer points of law, and British law at that. So does this one, so much so that the original title is a perfect fit. That the story takes place at Christmas time is almost entirely incidental. It’s only an excuse to get several members of one family together, along with a few choicely selected friends, at one time, at one place, and snowed in with no recourse to get along with one another – or not.

There are two detectives of note. First by default, Sergeant Rogers, the bodyguard of Sir Julius Warbeck, M.P.; and secondly — and one wishes that this were not the only detective he ever appeared in — Dr. Wenceslaus Bottwink, a history professor and a refugee from many ism’s in Europe. It is Bottwink who does the true detective work, looking on as an interested observer of both British society at the time and the small microcosm of the same that find themselves isolated in Warbeck Hall, the “oldest inhabited house in Markshire.”

In terms of “fair play” detection, it might help the reader if he or she were a historian him or herself, but on reflection at book’s end, I think the motive should have been clear, or at the least, clearer than it was to me at the time.

One disappointment to me, after finding myself elated at the early-on discovery of the kind of story I was in for, was that the book felt too short, without quite enough suspects nor sufficient false trails to be led down. There is an explanation for this. According to mystery historian Tony Medawar, An English Murder was based on “Murder at Warbeck Hall,” a half hour radio play broadcast by the BBC in 1948.

No matter. I will always gladly accept examples of detective work like this, no matter if short work is made of it or not. The social unrest that provides the setting is a pure 100% bonus.

Sat 9 Feb 2008

I have sad news to report. There is an obituary in today’s New York Times for one of the mystery field’s grandest ladies, Phyllis A. Whitney. The following is the mini-biography that appears in A COMPLETE SET OF FINGERPRINTS: An Annotated Checklist of the Fingerprint Mystery Series published by Ziff-Davis, by Bill Pronzini, Victor Berch & Steve Lewis:

Of the various authors who wrote books for the Fingerprint line, Phyllis A. Whitney may not have the honor of having written the most books in her career – that honor goes to Judson Philips / Hugh Pentecost – but the time span involved in her case is surely the longest. Red Is for Murder was her first work of adult fiction, published when she was 40 years old. The most recent of her approximately forty novels is Amethyst Dreams (Crown, 1997), which was published when she was 94. That book is still in print, as are many of her earlier ones. [FOOTNOTE.]

In 1988 the Mystery Writers of America gave Ms. Whitney their Grand Master award for lifetime achievement, the highest honor they can bestow. As for the type of story on which her reputation is based, she is an author whom the New York Times once called the “Queen of the American Gothics.” Last year [2006] at the age of 102, it is reported, she was working on her autobiography. (The link will take you to her home page.)

For several years after Red Is for Murder, Whitney concentrated on children’s fiction. (Her first book, A Place for Ann (1941) was also in the young adult category.) Her next adult mystery, The Mystery of the Gulls, did not appear until well after the war was over, in 1949. The majority of the titles for which she is best known were published in the 1960s through the 1980s.

The jacket blurb for Red Is for Murder reads in part as follows: “How does it feel to be in a big [Chicago] department store after the customers have hurried home and the lights have been darkened so that eeriness reigns over the vast reaches of the floors? To Linell Wynn, who writes sign copy for Cunninghams’, such a scene has always seemed perfectly natural until the day that murder walks the floors at dusk.

“The matter-of-factness of the police as they question people whom she knows, works with every day, does nothing to dispel the feeling that they are only temporarily holding back the powers of darkness. Evil has struck once – and evil is hovering, waiting to strike again [and soon] she stumbles upon death for the second time.”

FOOTNOTE. Phyllis A. Whitney was born in Yokohama of missionary parents. Her middle name is “Ayame,” which is the Japanese word for “iris.” Her mother’s first marriage was to Gus Heege, who claimed to be the originator of the Swedish dialect play, his most famous being “Yon Yonson.” After Whitney’s father died in Japan, she and her mother returned to the US, where in 1920 (according to census records) she lived with her mother in the Devin household, where her mother worked as a maid. In 1930 as Phyllis Garner, she worked as a librarian in a circulating library in Chicago. She must have married George Garner around 1925, as she claimed to have been married for five years. For more information on her long and productive life, follow the link above to her home page.

[UPDATE] In a later post, mystery novelist and long-time fan Dean James shares with us his memories of Phyllis Whitney.

« Previous Page — Next Page »

Phyllis A. Whitney’s books have been great favorites of mine for as long as I remember. I discovered her juvenile mysteries about the same time that I discovered her adult suspense novels, and I read both groups of books with great pleasure. Growing up on a farm in Mississippi, I did all my world-traveling in those days through books. Miss Whitney took me to far-flung, exotic places that I could never hope to go on my own, and after I read one of her books I felt I had been to those locales, if only for a brief while.

Phyllis A. Whitney’s books have been great favorites of mine for as long as I remember. I discovered her juvenile mysteries about the same time that I discovered her adult suspense novels, and I read both groups of books with great pleasure. Growing up on a farm in Mississippi, I did all my world-traveling in those days through books. Miss Whitney took me to far-flung, exotic places that I could never hope to go on my own, and after I read one of her books I felt I had been to those locales, if only for a brief while.