April 2009

Monthly Archive

Wed 15 Apr 2009

MARK DENNING – Beyond the Prize. Jove V4473, paperback original; 1st printing, 1978.

This is the third book of a series featuring John Marshall, the one-armed secret agent (not to be confused with Dan Fortune, the one-armed private eye).

This time Marshall is after an AWOL colleague in Ireland, where he tangles with the IRA, the KGB, and just about everyone else.

There’s plenty of action, plus a plot twist or two that you don’t really expect in such an action-oriented story, and Marshall has an enjoyable toughness. There aren’t too many books of just this kind being written today, and if you liked James Bond, give it a try.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 3, May-June 1979.

Bibliographic data: [Taken from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

DENNING, MARK. Pseudonym of John Stevenson, ?-1994. JM = John Marshall.

Shades of Gray. Pyramid, pbo, 1976. JM

Die Fast, Die Happy. Pyramid, pbo, 1976. JM

Beyond the Prize. Jove, pbo, 1978. JM

The Swiss Abduction. Leisure, pbo, 1981. JM

The Golden Lure. Tower, pbo, 1981. JM

Din of Inequity. St. Martin’s, hc, 1984.

Ransom. Pocket Books, pbo, 1990.

Wed 15 Apr 2009

KATHLEEN WADE – Crime at Gargoyles. Hutchinson, UK, hardcover. No date stated [1947].

The current, updated entry for Kathleen Wade in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, looks like this:

WADE, KATHLEEN (Nesta Knight). 1903 -1986. SC: Detective Inspector (Hamilton) Drake, in at least those marked HD.

Death at Aranshore (Gifford, 1942, hc)

Death on ?Calamity” (Gifford, 1945, hc) [England; Ship]

Crime at Gargoyles (Hutchinson, 1947, hc) [England] HD

A Cloak for Malice (Hutchinson, 1949, hc) [England]

The Dark Moment (Hutchinson, 1951, hc) [England] HD

Act of Violence (Hutchinson, 1954, hc)

Note that some of this information appears only in the online Addenda, which adds some facts uncovered by British mystery bookseller and researcher Jamie Sturgeon. He also notes that “she lived with the [noted] sculptor and writer Eric Benfield (if you do a Google search you will find a little bit about both of them).”

The link will lead you to one such page; more than likely there are several others. It was also Jamie who discovered that Inspector Drake appeared in at least two of the books, Crime at Gargoyles being one of them.

Drake doesn’t enter in until well after halfway through, however. Until then the story focuses solely on John Shirley, home from the Far East as a war correspondent on sick leave — a “recent breakdown.”

Which helps explain, perhaps, why he does what he does when he moves a body he finds in his guest lodgings at Max Tarn’s manor house, a former monastery called Gargoyles. He was shattered at first by meeting his ex-fiancee at the dinner party the night before, but matters are made worse when the dead man turns out to be the fellow she chose as a husband instead, Tarn?s stepson.

Strangely enough, when he dumps the body in a small nearby stream — although he realizes how neat a frame it is — he’s thinking as much of the old man who’s been taking care of the guest lodge, a fellow named Beal, who also had good reason to hate the dead man. But good intentions often lead to bad consequences, and of course that is what they do here.

It isn’t until another victim is found, one presumed to be suicide, but Shirley thinks not, that he decides to call on his good friend Inspector Drake, eventually confessing all. By that time, the case has evolved into as much a thriller novel as a detective story.

One possible definition of a thriller novel: one that you pick up at midnight to read and at 2:30 you discover you haven?t put it down yet.

Of course when you do finish it, perhaps not the same evening, you may often look back and see how inconsequential it all was, as is the case here, but not while you are reading it, not at all.

Wed 15 Apr 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Francis M. Nevins:

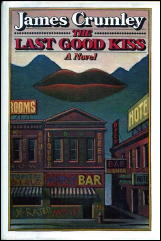

JAMES CRUMLEY – The Last Good Kiss. Random House, hardcover, 1978. Reprint paperback: Pocket, 1981. Vintage Books, trade ppbk, 1988.

Since the death of Ross Macdonald and on the basis of just three novels, James Crumley has become the foremost living writer of private-eye fiction. Carrying on the Macdonald tradition in which the PI is no longer macho but a man sensitive to human needs, torn by inner pain, and slow to use force, Crumley has moved the genre into the Vietnam and post-Vietnam era.

His principal setting is not the big city as in Hammett and Chandler nor the affluent suburbs as in Macdonald, but the wilderness and bleak magnificence of western Montana. His prevailing mood is a wacked out empathy with dopers, dropouts, losers, and loonies, the human wreckage of the institutionalized butchery we call the “real world.” Nobility resides in the land, in wild animals, and in a handful of outcasts — psychotic Viet vets; Indians, hippies; rumdums; and love-seekers — who can’t cope with life.

Crumley’s detective characters have one foot in either camp. Milodragovitch, the protagonist of The Wrong Case (1975) and Dancing Bear (1983), is a cocaine addict and boozer, the child of two suicides, a compulsive womanizer like his wealthy Hemingwayesque father; a man literally marking time until he will turn fifty-two and inherit the family fortune, which his pioneer ancestors legally stole from the Indians.

Sughrue from The Last Good Kiss has a background as a Nam war criminal and an army spy on domestic dissidents and he’s drinking himself to death by inches. Yet these are two of the purest figures in the history of detective fiction, and the most reverent toward the earth and its creatures.

Crumley has minimal interest in plot and even less in explanations, but he’s so uncannily skillful with character, language, relationship, and incident that he can afford to throw structure overboard. His books are an accumulation of small, crazy encounters, full of confusion and muddle, disorder and despair, graphic violence and sweetly casual sex, coke snorting and alcohol guzzling, mountain snowscapes and roadside bars.

When he does have to plot, he tends to borrow from Raymond Chandler. In The Wrong Case, Milodragovitch becomes obsessed by a young woman from Iowa who hires him to find her missing brother, a situation clearly taken from Chandler’s Little Sister (1949).

The Last Good Kiss, perhaps the best of Crumley’s novels, traps Sughrue among the tormented members of the family of a hugely successful writer, somewhat as Philip Marlowe was trapped in Chandler’s masterpiece, The Long Goodbye (1954).

In Dancing Bear, which pits Milodragovitch against a multinational corporation dumping toxic waste into the groundwater, the detective interviews a rich old client in a plant-filled solarium just like Marlowe in the first chapter of Chandler’s Big Sleep (1939).

None of these borrowings matter in the least, for Chandler’s tribute to Dashiell Hammett is no less true of Crumley: He writes scenes so that they seem never to have been written before. What one remembers from The Last Good Kiss is the alcoholic bulldog and the emotionally flayed women and the loneliness and guilt.

What is most lasting in Dancing Bear is the moment when Milodragovitch finds a time bomb in his car on a wilderness road and tosses it out at the last second into a stream and weeps for the exploded fish that died for him, and dozens of other moments just as powerful.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Bibliographic data [updated]:

MILO MILODRAGOVITCH [James Crumley]

The Wrong Case. Random House, 1975.

Dancing Bear. Random House, 1983.

Border Snakes. Dennis McMillan, 1996. Note: Crumley’s other PI character, C. W. Sughrue, also appears in this book.

The Final Country. Mysterious Press, 2002.

Tue 14 Apr 2009

JAMES CRUMLEY – The Last Good Kiss. Random House, hardcover, 1978. Reprint paperback: Pocket, 1981. Vintage Books, trade ppbk, 1988.

Most private eyes work out of huge metropolitan cities like New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Through the years a handful of others have based their somewhat seedier operations in midwestern population centers such as Chicago, Cleveland and Indianapolis.

On television this season there is an example of how a Las Vegas detective goes about his business, but you’d have to admit that the glamor and glitter of that particular show is far from typical of mainstream America, and so it remains far more reminiscent of that old stand-by of the pulp magazines, the Hollywood private eye story.

C. W. Sughrue’s home is Montana, however, and his outlook on life and happiness, or the pursuit thereof, is correspondingly closer to a segment of American demographics long ignored by other authors, obsessed with the bizarre vagaries of life in southern California, for example.

Rocky Mountain jade. Sughrue is often dirty and unshaven, and a good deal of the time he’s drunk, or close to it, but never obnoxiously so. He’s as much a combination of hippie and redneck as either variety of humanity could ever recognize as possible. He mixes affably with both, and yet he has the same moral obligation to himself that all the great private detectives of literature have had to have hidden inside.

The story, as it strips his character carefully away in layers, is so intensely revealing that for him to become yet another series creation would be close to pointless.

As muddled — or even more so — as any in real life, the story begins with a hunt for a famous bar-hopping poet and novelist who takes him on a binge through several states before he’s found, but before he can return home Sughrue is sidetracked into chasing down a runaway girl, lost and not found in the pornographic environs of San Francisco ten years earlier.

Lives are muddled as well, and revelations are painfully hard to come by. The tale that Crumley has to tell builds slowly and easily into a climax that explodes with all the emotional thrill of a gut-satisfying revenge about to be released.

Crumley is not the new Hammett. He’s closer to Chandler, if names must be dropped, but in several ways he’s the equal of both, their peer. In fact, he’s that rarity, an authentic rough-hewn original, and they don’t happen along very often.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 3, May-June 1979 (very slightly revised). This review also appeared earlier in the Hartford Courant.

[UPDATE] 04-14-09. Some comments from me, thirty years later. I have not re-read the book at any time between then and now.

(1) Here’s the first line of the book, still one of the more memorable ones of hard-boiled crime fiction, in my opinion:

“When I finally caught up with Abraham Trahearne, he was drinking beer with an alcoholic bulldog named Fireball Roberts in a ramshackle joint just outside of Sonoma, California, drinking the heart right out of a fine spring afternoon.”

(2) I do not know what TV show I was referring to in the second paragraph. I could look it up, but if you know without resorting to a reference book, leave a comment. I have no prizes to offer to the first one to come up with the correct answer, I’m sorry to say.

(3) It is difficult, sometimes, for a reviewer to say exactly why he or she likes a book. It is far more easy to say why you don’t. Reading this review for the first time in the same 30 years, I’m disappointed (but not surprised) that I wasn’t more clear as to what I read that produced this rave review. (In the MYSTERY FANcier version, but not the one in the Courant, you might like to know that I included a rating: A Plus.)

(4) Somewhere in the middle I suggested that it would be difficult for Crumley to continue using C. W. Sughrue as a series character. As we know now, there were other books, but as I recall none of them knocked my socks off as much as this one. I’ll add a complete list below. (It did take 15 years for Crumley to write about Sughrue again.)

(5) At the end of the review, I compared Crumley to both Hammett and Chandler, saying he was their equal. In the long run, while the author and his books are both cult favorites, I don’t think his career was anywhere near as successful (or known today) as I thought it might. Am I wrong about this?

C. W. SUGHRUE. [James Crumley]

* The Last Good Kiss. Random House, 1978.

* The Mexican Tree Duck. Mysterious Press, 1993.

* Border Snakes. Mysterious Press, 1996. Note: Crumley’s other PI character, Milo Milodragovitch, also appears in this book.

* The Right Madness. Viking, 2005.

Mon 13 Apr 2009

THE GOLDEN AGE OF BRITISH MYSTERY FICTION, PART IV

Reviews by Allen J. Hubin.

Hal Pink’s obscurity in this country is total. None of his thirteen books from 1932 to 1941 was published here, and I think Pink escapes notice in every commentary on the genre known to man or beast.

So at least I wasn’t over-expectant in approaching The Strelson Castle Mystery (Hutchinson, 1939), but it turned out to be a cheerful, fast and gratifying read. No detective story, this; it’s a thriller, with bad guys and good guys clearly identified at the outset.

The good guys are a trio of bachelors, vacationing in Europe’s vest-pocket kingdom of Zovania. The bad guys are trying to grab control of a mysterious fortune, apparently hidden somewhere in Zovania’s titular castle, which has just been inherited by beautiful British opera star Coralie Mayne.

The fun begins at the Zovanian border, and then it’s pell mell action all the way, in two batches – since the chief villain, vanquished once, brews another rotten scheme and surfaces again in his sewer.

Burford Delannoy wrote a number of volumes of crime fiction around the turn of the century, some of which are collections of detective short stories and vanishingly scarce. Denzil’s Device (Everett, 1904) is one of his novels and, for all its antiquity and stylistic peculiarity, it surprised me with its effectiveness, especially in the portrayal of odious villainy.

The peculiarity lies in a pronounced tendency toward subjectless sentences (the subject of the previous sentence applies but is left unstated); this is compensated for by a wryly humorous turn of phrase. And while the basic outcome is fairly well assured from the outset, some uncertainty and suspense about details develops.

Denzil is wealthy and evil. He lusts after the daughter of a judge, but she rejects him for an actor. Denzil’s device is a scheme to acquire the girl (willingly or not) and revenge himself upon the actor. For his purposes he makes use of a murderous lowlife and an embittered mimic; for his downfall the careful attentions of Detective Doyle and colleagues must be praised.

My only reading of the works of Annie Haynes involves The Blue Diamond (Lane, 1925), which I found effective — surprisingly effective, even, in creating complexity and mystification and in arousing my interest.

We meet the wealthy and titled Hargreaves, whose estate lies near Lockford in Devonshire, and who own the titular gem. A beautiful young woman, afraid and bereft of her memory, is found one night on the estate. The Hargreaves allow the woman to make the manor her home until her memory returns, or until her family can be traced.

She soon wins the hearts of most of the household, especially that of Sir Arthur, the impressionable male head of the line who is just reaching his majority. No trace of the woman’s earlier existence can be found; her memory does not return. She stays on, and Sir Arthur’s swoon deepens.

Not everyone, however, finds her credible, and the disappearance without trace (apparently through locked doors) of a nurse brought in to aid her recovery casts a pall on the manor. And brings in the police…

NOTE: Go here for the previous installment of this column.

[EDITORIAL UPDATE] 04-13-09. There are few authors so obscure that no one recognizes their name. In spite of the fact that not a single one of Hal Pink’s fourteen mysteries is offered for sale online right now — I just looked — Bill Pronzini had this to say when this set of reviews first appeared:

“One minor point in re Hal Pink: It’s true that none of Pink’s novels was published here in book form, but he was published in the U.S. A handful of his short stories appeared in such magazines as Mystery (The Illustrated Detective Magazine) and Street & Smith Detective Story in the early 30s. Pretty good stories, too.”

Steve again: There’s nothing like a comment like that to prompt a checklist. I’ve come up with three stories from US magazines, but if someone more knowledgeable than I knew more about the British pulps than I do, I would expect the list to be a whole lot longer.

The Blond Raffles, Mystery, February 1934.

Bat Island, Mystery, March 1934.

The Fires of Moloch, Detective Story Magazine, September 1939.

Some time later, I heard from Christine Craghill, a relative of Mr. Pink’s whom I corresponded with for a while. I’ve lost contact with her, so I haven’t asked, but I hope she doesn’t mind my reprinting some of the information she found out about him. I’ve left out a good deal, but this is the essential data:

“Hal’s real name was Harry Leigh Pink (Leigh being his middle name, given in respect of his step grandfather Edmund Leigh) and he was born in 1906 on the Wirral Peninsular in Cheshire, England. He was the son of my grandfather’s brother Frederick Pink and his wife Ethel. So I was right with my first hunch about him, he was my father’s cousin and therefore my second cousin. […] He died in Bakersfield [California] in 1973.”

In her first email to me, Christine thought that Hal Pink’s name was really Percy Pink, which is the information that’s given in Part 31 of the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin. This she corrected in a later email, having discovered that Hal and Percy were actually brothers.

One last note: Hal Pink’s The Test Match Mystery (1941) is mentioned very briefly by Marv Lachman in an article he wrote called “A Yank Looks at Cricket and the Mystery Story.” Worth a look, I think, if you haven’t seen it before.

Wed 8 Apr 2009

Of necessity, I’ll be taking a break from blogging for the next week or so. My doctor and I are working on the problem. With thyroid disorders, it’s awfully tough to keep the dosages right. Lots of hills and valleys, as you’ll know if you’ve been following this blog long enough.

If I owe you an email, and I probably do if you’ve emailed me since the middle of last week or so, I’ll respond directly as soon as I get caught up a little.

Best wishes for the holiday season. I’ll be back when I can.

— Steve

Sun 5 Apr 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

HAL GLATZER – The Last Full Measure.

Perseverance Press; trade paperback original; April 2006.

Number three in the continuing mystery-solving adventures of itinerant 1940s swing band musician Katy Green turns out to be measurably better than number two, A Fugue in Hell’s Kitchen (2004), in my opinion, but still not nearly as fine as number one, Too Dead to Swing (2002), which is still the best of the three so far.

The primary setting for Katy’s latest adventure is an ocean liner that is headed for Hawaii in December, 1941.

“Ah, ha!” you say. Yes, and you’d be right.

It is indeed one of those novels in which the reader knows exactly what is in store, but for the passengers and crew, all they’re aware of are rumbling war clouds somewhere off in the distance (but getting closer and closer as time goes on). Katy is part of an all-girl group hired to entertain the passengers, and while you might think impending events would be trouble enough, it is not so.

There is a murder on board, but as it is also one with no real suspects. Once the ship arrives in Hawai’i, there is (strangely) nothing to forestall a side journey by a subgroup of the all-girl orchestra and various other passengers to locate a treasure buried by native Hawai’ians during a failed insurrection against the haoles in control of the islands many years before.

Of course this recitation of historical events requires a couple of short lectures, but while while they’re necessary, they also slow the action to a temporary crawl.

Soon enough, however, it is back to the still unsolved murder, committed by one of the dumbest villains in print, magnified by two events having probabilities of say, one in a million each. (Since the events are not likely to be independent, the overall combined probability of the two events both happening is NOT found by multiplying the two individual probabilities together, so perhaps it’s not as bad as it sounds.)

Other than that, the travelogue and on the on-board camaraderie are nicely done and may be in themselves worth the price of admission. The author certainly knows his music, and it shows.

— March 2006

Note: A shorter version of this review appeared in Historical Novels Review.

[UPDATE] 04-06-09. This was, alas, the last of Katy Green’s adventures in print, so far. Author Hal Glatzer is also a playwright as well as a writer and (not surprisingly) a musician. You can visit his website here.

Sun 5 Apr 2009

THE GOLDEN AGE OF BRITISH MYSTERY FICTION, PART III

Reviews by Allen J. Hubin.

My first sampling of British author John Laurence, The Fanshawe Court Mystery (Hodder & Stoughton, 1925), quite encourages me. This is a well-paced tale, nicely complex in plotting and properly mystifying.

Sometime detective story writer John Martin is riding his motorcycle along a rural lane one rain-filled night, headed for home, when flagged down by the beautiful girl he’s worshiped from afar but not yet met. The girl has come through a forest path and urgently asks a ride to the station so she can catch the train to London.

He helps her, and later learns that a reclusive local resident has been found murdered along that path. Why was he killed, and what roles do the girl and her dragon-aunt play? Supt. Barlow seems not to be making much headway, so Martin and a crime reporter do their own digging, as much to save the girl as anything else. Gradually threads of conspiracy, fraud, murder and revenge emerge.

Ripe for Development (Cassell, 1936) is one of several novels by John Gloag about Lionel Buckby, and it’s a rather peculiar affair. Buckby has private money and only one passion: old furniture. He’s not very fond of the U.S…

“There was no sherry in America; nobody had a palate for wine; nobody really understood comfort – they gave you plumbing, central heating, air-conditioning, non-stop noise and high speed and called the whole thing luxury and progress. It was good to be back in real civilization.”

…and he’s one of the least perceptive protagonists in the genre. He gets mixed up with a crooked New York art importer and a pair of Chicago gangsters and never catches the drift. The results are nearly fatal – but New York’s Insp. Slamble, allied with the Yard at the end, comes to the rescue. The scheme has something to do with furniture bearing Buckby’s authentication being shipped across the Atlantic. Amusing in spots but not impressive.

Another British author of total obscurity is Josephine Plain, who perpetuated three mysteries featuring Colin Anstruther in the 1930s. One of these is The Secret of the Snows (Butterworth, 1935), set in a Swiss mountain village.

Detestable chemist Alfred Gitterson married a young and beautiful and fearsomely superficial wife and in due course got himself strangled on a mountainside. Or so it appears at first glance. At second glance circumstances change drastically and it seems physically impossible for only one person to have done the deed.

Anstruther is providentially vacationing on the spot. He wants no part of the matter, but his old friend, Swiss detective M. Maraud, draws him in – and in any case Colin had suspected one of the principals of murder in an earlier case.

Various characters are slowly revealed for what they are as Colin and Maraud struggle against an impossibility which gets worse the more they dig. Pleasant and well-written as this is, it neither plays fair nor convinces nor satisfies in resolving the puzzle.

NOTE: Go here for the previous installment of this column.

Sat 4 Apr 2009

LES SAVAGE, JR. – Gambler’s Row.

Leisure, paperback reprint; 1st printing, February 2003. Hardcover edition: Five Star, February 2002.

Yes, this is a western, and if you’re a mystery fan only, you can go right on to the next review, if you prefer. But over the past few years Five Star has been doing western fans a great big favor in publishing collections of vintage pulp stories like this one, and thanks to Leisure Books as well, many of them are now available in cheaper editions.

There are three short novels in this one, all previously appearing in the badly flaking pages of Lariat Magazine, circa 1945-48. But where’s the crime connection, you ask? I’m glad you did, since I was coming to that. In “Gambler’s Row,” the title story, a wandering cowpoke named Drifter (well, yes) is hired by the female owner of the Silver Slipper to locate the sole witness to a murder.

In “Brush Buster” the only crime is cattle rustling, but it does take some detective work on the part of small-scale rancher Nolan Moore to track them down (and win the hand of lush, full-bodied Ivory Lamar). And in “Valley of Secret Guns” one-armed bronc-buster Bob Tulare is suspected by a gang of rustlers and killers of being a private detective, working undercover to bring them to justice. There is, of course, a woman involved as well.

As you can probably tell, Al Hubin isn’t likely to include this book in the latest edition of his Bibliography of Crime Fiction, nor would I if I were he, to tell you the truth, but like most westerns, it’s not all that far afield. The stories are melodramatic, especially the first one; humorous, especially the last one; romantic, all three of them; and, most importantly, authentic, again all three of them.

If you read carefully enough, you can learn how to track someone on horseback without being spotted; how to retrieve cattle used to running wild in the mesquite and thick brush along the Mexican border; and how to break killer horses at five dollars a bust.

There are cowboy terms in this book that I’ve never heard of, and I don’t think Savage made them up. From page 160: “Center-fire rig popping and snapping beneath him, Tulare unhitched his dally … he didn’t have to get too close with forty-five feet of maguey in his hand.”

Savage also writes great fight scenes, a few that go on for pages. Not great literature, by any means, but for the market for which they were written, these stories are top of the line.

Sat 4 Apr 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

DENISE MINA – Field of Blood. Little, Brown; hardcover, July 2005; Bantam, pb, April 2006.

— The Dead Hour. Little, Brown; hardcover, July 2006; Back Bay Books, trade pb, February 2008.

— Slip of the Knife. Little, Brown; hardcover, Februray 2008. First published as The Last Breath (UK, Bantam Press, 2008).

I thought that Denise Mina’s Garnethill (Carroll & Graf, 1999) marked the debut of a outstanding crime writer. I was less taken with her stand-alone novel Deception (Little, Brown, 2004). But her new series with neophyte reporter Paddy Meehan has, for me, validated the promise of her early work.

Paddy, a bright young woman obsessed with a negative self-image, establishes a tentative hold on the bottom rung of the journalistic ladder in a small Scottish newspaper in Field of Blood, her first appearance, while in The Dead Hour she has risen to full-time employment on the night shift, hoping to get the story that will gain her the respect of her colleagues, and make her career.

She lucks into it but with bent cops trying to effect a coverup and both Paddy’s life and career on the line, she follows leads that could prove her suspicions or kill her.

In Slip of the Knife she’s achieved her journalistic ambition with a position as a newspaper columnist that brings her recognition if not the complete personal satisfaction that is the more elusive goal. When she learns that a close friend and sometime lover has been murdered and that she has inherited his scrubby estate, she finds she has also inherited his troubled history and deadly secrets that now threaten her.

This still developing series has the drive of the early Rankin Rebus outings, with a potentially self-destructive protagonist who rivals Rebus in her ability to court disaster without falling prey to it. She may not ask for the reader’s attention, but the power of her narrative voice demands it.

« Previous Page — Next Page »