May 2009

Monthly Archive

Tue 19 May 2009

The connection between noted director Joseph Losey and the movie Hotel Reserve may be slim, but in the comments that follow my recent review of the film, a long discussion about the man and his movies has been taking place, perhaps without your noticing it.

The movies that have come up for discussion range from Modesty Blaise to Boom!, The Lawless, The Servant and several others. If you’re a fan of his work, or would like to read more about him, follow the link above.

Mon 18 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

EDGAR WALLACE – The Stretelli Case and Other Mystery Stories. International Fiction Library / World Syndicate, hardcover, 1930.

Edgar Wallace (1875-1932) was a publishing phenomenon in his day, his name being synonymous with the word “thriller,” a genre some would credit him with inventing.

Wallace was incredibly prolific; he belongs to that group of logorrheic authors — Erle Stanley Gardner, John Creasey, Charles Dickens, and a few others — who wrote books like their hair was on fire. One would naturally expect a lowering in quality with an increase in quantity (it seems to be a natural law), but we’ll leave that judgment to others who have waded through most, if not all, of Wallace’s output.

The Stretelli Case seems to be a brief sampling of his work taken from other collections, consisting of eleven short stories loosely classified as “mysteries.” While thriller elements are certainly present in most of them, the stories, with one exception, are indeed mysteries of one sort or another (the exception being “The Know-How”).

Several stories feature detectives per se; most of them have people under pressure who must decipher baffling situations in order to correct deformations in the social fabric — or just to save their imperiled lives or reputations.

The dates and places of first publication for these stories are nowhere in the book. (Sources for some are included in Hubin and will be noted here.)

CONTENTS:

● 1. “The Stretelli Case.” [Reprinted in The Thriller #286, 28, July 1934.] Detective-Inspector Mackenzie’s last case provokes in him that “unquenchable antagonism between his sense of duty, his sense of justice, and his grim sense of humor.” Dr. Mona Stretelli of Madrid comes to him, convinced that Margaret, her sister, has been murdered by her husband, Mr. Morstels.

Margaret, however, had a bad reputation with the authorities, since she “belonged to the bobbed-hair set that had its meeting place in a Soho restaurant. She was known to be an associate of questionable people; there was talk of cocaine traffic in which she played an exciting but unprofitable part,” and so on. Imagine Mackenzie’s surprise, then, when Mona does a complete about face and announces her intention to marry Morstels; and of what significance is it when Mona purchases a paste ring once owned by Marie Antoinette?

Be prepared for a plot twist near the end.

● 2. “The Looker and the Leaper.” Is it always true “that the ultra-clever father has a fool for a son”? Dick Magnus and Steven Martingale, both scions of wealthy business magnates, wooed Thelma — “cold and sweet, independent and helpless, clever and vapid”–and “To everybody’s surprise, she married Dick.”

Perhaps one could write it off to hormones, those “little X’s in your circulatory system which inflict upon an unsuspecting and innocent baby such calamities as his uncle’s nose, his father’s temper, and Cousin Minnie’s unwholesome craving for Chopin and bobbed hair.”

By story’s end, we are left with a conundrum: Did the leaper fail to look before the looker made his leap, or was it all just a horrible accident?

● 3. “The Man Who Never Lost.” [Town Topics, 27 December 1919; reprinted in The Thriller #290, 25 August 1934.] Aubrey Twyford, The Man Who Could Not Lose, has won over 700,000 pounds in ten years at Monte Carlo’s gambling casinos; but when Bobby Gardner decides to go for broke and try to win enough to marry Madge Brane, will Twyford divulge his unbeatable system and thus guarantee his own loss?

● 4. “The Clue of Monday’s Settling.” Five million pounds’ worth of British, French, and Italian notes go missing from a strong-room on a trans-Atlantic ocean liner, and John Antrim and his daughter May face certain financial ruin; also missing are six towels, a fact of consuming interest to Bennett Audain, who “certainly understood the psychology of the criminal mind better than any police officer that ever came from Scotland Yard–an institution which has produced a thousand capable men, but never a genius.”

For him, a word association test clinches it: If you heard the word “key,” would you think “wind”; and if the word was “Monday,” would you think “unpleasant”?

● 5. “Code No. 2.” [The Strand, April 1916.] It’s spy-versus-spy on the eve of World War One: Sir John Grandor, Chief of Intelligence, has his doubts about one of his own people; even though the one he suspects is killed, it still remains for a smart female agent to thwart a plan to transmit the stolen code to the Central Powers.

(The code-stealing gadget, by the way, is remarkably high-tech and seems straight out of a James Bond movie.)

● 6. “The Mediaeval Mind.” [Reprinted in The Thriller #291, 1 September 1934.] Jean D’Orton, half-sister to the D’Orton brothers, is very, very rich and anxious to marry Jack Mortimer; the fact is, however, she doesn’t come into her fortune until she is twenty-five or gets married. In the meantime, her half-brothers have been, shall we say, improvident with her money, and the prospect of Jean’s wedding has dire implications for them: “It means,” says one, “penal servitude for all of us.”

What to do. Well, how about shanghaiing Jack and forcing Jean to marry an escaped convict; that always works, doesn’t it? The biters get very decisively bit in this one.

● 7. “The Know-How.” Storm and stress in the production of a musical play, one in which no one, not even the producer, has any confidence. A Cinderella story for the understudy, but a mystery story this is not.

● 8. “Christmas Eve at the China Dog.” The paths of old war buddies intersect when Walter Merrick approaches air taxi pilot Tam M’Tavish, offering him five hundred pounds to help him perform a despicable act vis-a-vis another man’s wife; then comes that fateful evening in Paris at the “Chien de Chine,” and Tam quite unwittingly lays the foundation for a perfect alibi.

● 9. “The Undisclosed Client.” [Hearst’s Magazine, July 1926.] Lester Cheyne is a lawyer whose success lies, shall we say, outside the normal channels of the law; putting pressure on wealthy people for their indiscretions is his stock in trade, and everything is humming along nicely until he encounters the Girl in the Brown Coat….

● 10. “Red Beard.” [Colliers 24 May 1919.] A spy is murdered in his flat, yet he is clearly overheard telling his assailant that he’s glad his own gun jammed; Brinkhorn and Templey investigate on behalf of the Department.

By the time they’re finished, Templey will have connected the disparate dots of the spy executed in the Tower of London, a disappearing index card, a ship sinking in the Irish Sea, a colored birth-mark on a child’s leg, bread passed and wine poured with the left hand, and his partner’s resignation from the Department.

● 11. “The Man Who Killed Himself.” [The Royal Magazine, February 1920.] For seventeen years Preston Somerville has been blackmailed by a nonentity named Templar; but when the latter drags Somerville’s daughter into the glare of hostile publicity, Preston is moved to desperation, his actions taking him through the valley of the shadow…..

Sun 17 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

RITA MAE BROWN & SNEAKY PIE BROWN – Catch As Cat Can.

Bantam; paperback reprint, Feb 2003. Hardcover edition: March 2002.

Yes, Virginia, there really is a Crozet. In Virginia, that is, a small town of about 2000 inhabitants (not including cats), snugly nestled into the foothills of the Blue Ridge Montains. And the home of Mary Minor Haristeen, known to her friends as Harry, the postmistress of Crozet, and the Mom to Mrs. Murphy and Pewter (both cats) and Tee Tucker (a corgi).

That the Mrs. Murphy mysteries are popular almost goes without saying, as this is the 10th in the series, but on the other hand, I am also positive that there are many many mystery readers who would never never read a mystery that has talking animals in them.

To each other, that is, not to humans, who are ever a source of humor and resignation to them. Not to mention food.

From page 3: “‘I’m standing vigil at the food bowl.’ Pewter zipped to the kitchen.” And here’s a typical cat way of expressing herself, from page 35: “Mrs. Murphy strode into the room, sat down on the coffee table, and yelled, ‘Everybody is horrible! Only I am perfect!'” Animals — and I never knew this before — are very blunt observers of the humans around them. Read page 144 and be convinced.

And Harry’s three companions — Harry once was married, but her ex is still friendly, and wants to be friendlier again, but she is not sure — do their best to assist in solving the mysteries involved in their books, but being unable to communicate with Harry in any useful manner, they are forced, alas, to allow her to muddle along without them.

In Catch As Cat Can, it takes 80 pages for the first death to occur — before that the only crime that occurs is a case of the stolen hupcaps — and the atmosphere is so low key that even then no one’s aware that murder has actually happened.

Rita Mae Brown is a well-known writer of Southern fiction, and she has the details of life in small town Crozet delineated perfectly, social structure and all, down to the finest details, but as a mystery writer, she’s a long way from being this generation’s Agatha Christie.

The investigation carried out by the local sheriff’s office is certainly up to any large city’s standard, but it’s still largely underwhelming and uninspired. There are heaps and heaps of speculation, most of it wrong, and no one asks the right question at the right time. And although there’s a great big huge Wrecker’s Ball of a finale, the solution is both (a) strictly from left field, and (b) simply too easy.

Harry, the two cats, the corgi, and all of her friends (and ex-husband) are certainly great people to sit down and visit with vicariously, though, and if you find yourself hooked, you’ll probably want to come back again and again.

— March 2003

[UPDATE] 05-17-09. I wouldn’t mind reading another in the series, but while I’ve had the chance, several times over, so far I haven’t. Others have taken up the slack, though. Since I wrote this review, only six years ago, another seven Mrs. Murphy books have been published.

Sun 17 May 2009

The Black Horse Extra website is designed primarily to promote Western fiction, and Westerns published by UK publisher Robert Hale in particular. The latest issue, however, as editor Keith Chapman told me in an email from him earlier this week, has at least one item of considerable interest to mystery fans as well.

The lead piece, though, is a long profile of western writer Gary Dobbs, aka Jack Martin, whose Tainted Archive blog is always worth a visit. Gary’s also a one man publicity factory for the revival of western fiction in general, making every effort he can to promote the genre and to keep it alive and well — and succeeding, too.

The direct connection to Mystery*File is further down the page, and at this point, I’m simply going to quote:

“A NUMBER of authors seem to abandon their series characters once they begin to tire of them — which I can certainly relate to — starting with Doyle and Holmes,” says Steve Lewis in a [comment to a]

post at his wide-ranging

Mystery*File blog.

Steve admitted it was no more than “a premise,” and counter-examples would strike him as soon as he had hit the submit button to circulate his view.

He went on, “But also sometimes (not always) their non-series books lack something their series characters provided … their previously established personalities that the books they’re in can rely on for easy reader recognition and (even better) a solid foundation from the very start.”

The BH Extra put Steve’s contention to a panel of BHW writers: Keith Hetherington (aka Jake Douglas, Tyler Hatch, Hank J. Kirby and Rick Dalmas), David Whitehead (aka Ben Bridges, Matt Logan and Glenn Lockwood), and Keith Chapman (aka Chap O’Keefe).

Some of the authors seem to be one side, while others are on the other. The consensus answer, if any is arrived at, appears to be “It all depends,” which although I’m not an author, would have to be the answer I’d give if I were one.

Of course there’s a lot more to it than that. Since mystery writers face the same dilemma, I think most mystery readers will enjoy the far-ranging discussion that follows. (Follow the link in the first paragraph above.)

Sat 16 May 2009

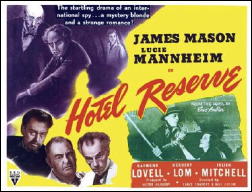

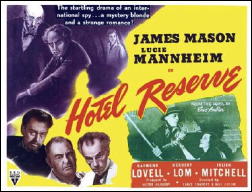

HOTEL RESERVE. RKO Radio Pictures-UK, 1944. James Mason, Lucie Mannheim, Julien Mitchell, Herbert Lom, Clare Hamilton, Frederick Valk, Raymond Lovell, Patricia Medina. Based on the novel Epitaph for a Spy by Eric Ambler. Directors: Lance Comfort, Max Greene (Mutz Greenbaum), Victor Hanbury.

There must be a well-known rule of thumb, something like Murphy’s Law except that I don’t know the name, that when a movie has three directors, it’s not very good. While there are some good moments in Hotel Reserve, it’s no exception to prove the rule.

I don’t think it was the author’s fault. Back in the 1950s when I first started reading “grown-up” mysteries, Eric Ambler was one of my favorite authors. His spy novels written in the 1940s were wonderfully descriptive and intense, filled with ordinary citizens getting into the most intricate plots — and all the better, finding their way out.

I’ll have to re-read them sometime. Perhaps they won’t hold up or match my memories, but I think they will. In Hotel Reserve it is a man named Peter Vadassy (James Mason), an intense medical student who’s half-Austrian and half-French and anxiously awaiting his French naturalization papers, who gets into trouble during a short vacation at a French seaside resort, circa 1939.

It seems that someone accidentally used his camera to take some photographs of a defense installation, and the police, particularly intelligence chief Michel Beghin (Julien Mitchell) are not amused. Although he knows Vadassy to be innocent, he sends him back to the hotel to find the real culprit, under the threat of deportation if he fails.

The set-up is fine. This had all the signs of a pretty good amateur detective story, but what follows instead is a mish-mash of comedy and inept B-movie clunks on the head and angry confrontations.

The other vacationers are difficult to keep track of — who’s who and why they’re there — even Vadassy’s would-be girl friend, Mary Skelton (Clare Hamilton).

That the latter is surprisingly wooden in both attitude and delivery is explained by the fact that this is the only movie she ever made. (It is claimed by several sources that Clare Hamilton was the sister of Maureen O’Hara; at least one person leaving comments on IMDB is not so sure.)

If you read through the list of the cast that I provided above — I didn’t list them all, as most of them have very small parts — and assuming that you recognize some of the names, you may pick out the true culprit(s) rather easily.

James Mason, alas, didn’t have that luxury. He does well in the part, frightfully earnest to the end, but he’s undone by an indifferent script, a ludicrous ending, and three directors, none of whom can be compared to, say, a certain Mr Hitchcock, except badly.

Sat 16 May 2009

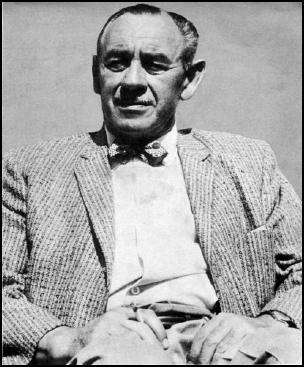

A couple of weeks ago, I posted an inquiry on the behalf of Charles Seper, who was looking for a photo of mystery writer Philip MacDonald.

He had only a small one at the time, and Juergen Lull found another small one that he sent me, which I posted here.

But from the back cover of the Doubleday edition of The List of Adrian Messenger, Charles was able to obtain what he was looking for, a large photograph of Mr MacDonald that he could use as part of a project he’s working on.

I’m grateful to him for sending it along. I was sure I’d seen one somewhere over the years. I’m not sure that this is the one I remember, but if it’s not, it’s close:

Sat 16 May 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE SECRET SIX. MGM, 1931. Wallace Beery, Clark Gable, Lewis Stone, Jean Harlow, Ralph Bellamy, Marjorie Rambeau, Johnny Mack Brown. Screenwriter: Frances Marion (later the author of a novelized edition). Director: George W. Hill.

I stumbled onto the last half of this crime film in Paris, while I was checking channels to find something other than the French-dubbed American TV series that seem to dominate French television.

The film was shown in the original English-language version and featured an impressive cast, as enumerated above, including Johnny Mack Brown in a non-Western role.

Beery and Stone form an unlikely pair as a crime Syndicate ganglord and a crooked lawyer opposed by a masked group of concerned citizens. Harlow is the good/bad girl, and Gable the undercover agent working to dethrone Beery and expose Stone.

Pre-classic-period MGM films don’t turn up on American TV these days, and it was a pleasure to see even part of this skillful thriller by another director previously unknown to me.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988, slightly revised.

[EDITORIAL COMMENT.] This was written, of course, before Turner Classic Movies came along. The Dark Ages are over, and movies of the same era as The Secret Six can be seen on TV several times a week. Nor are films with stars such as this one obscure any longer, even if the stars weren’t stars at the time. With both Gable and Harlow in the film, it’s easy to find stills taken from it to go along with reviews like this one.

Here’s another:

Fri 15 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Authors[22] Comments

DORNFORD YATES AND THE CLUBLAND HEROES

by David L. Vineyard

You should be warned before venturing into Dornford Yates country that there is no middle ground. Either you will be charmed and drawn in to the never-never land of his mostly between-the-wars adventure tales set in a Europe that owes more to Anthony Hope’s Ruritania or George Barr McCutcheon’s Graustark (Yates own Ruritania was the mythical Carinthia) than Eric Ambler’s back alleys, or you will throw up your hands in disgust. There’s little in the way of gray area when it comes to Yates.

Yates was in reality Major Cecil William Mercer (1885-1960), a solicitor and the son of a solicitor (two of the three writers Richard Usborne calls the “Clubland” writers, Yates and Buchan, are solicitors, which may or may not mean something) and a cousin of H.H. Munro (Saki), seems to have been a bit of a crank and certainly thoroughly unpleasant.

Pawky, bossy, and quick to take offense, his reaction to World War II was largely to complain he had to leave his French home, and his reaction to Post-War England was so violent he picked up and moved to Rhodesia where he ensconced himself in a small personal fiefdom.

Neither A. J Smithers’ biography (Dornford Yates, A Biography) nor O. F. Snelling’s biographical sketch (“The Disagreeable Dornford Yates” at Wes Britton’s SpyWise blog) manage to project a very likable individual, and Richard Usborne, whose book The Clubland Heroes is the major study of Yates, Sapper, and John Buchan’s fiction, recounts how Yates threatened legal action when contacted because Usborne misused the term cad. Luckily it is the fiction and not the man under review here.

From the early twenties into the fifties, Yates wrote some of the most delightful books of his era. The Wodehousian books about Berry and Company are light-hearted romps featuring upper middle class Englishmen and women and their hijinks at home and abroad (smuggling of goods to avoid the duties was virtually a sport in Yates novels). The tone is light and playful, and the books retain much of their original charm.

The thrillers feature much the same European settings, and Jonah (Jonathan) Mansel ties the two types of books together, but while he’s still bossy in the Berry books, the Mansel of the thrillers is an altogether more dangerous character who once killed a man (the splendidly named Barabbus) with a single blow of his fist. (William Chandos, Mansel’s second in command and hero of his own books also does for a villain with a single blow, though in his case, Goat, is only a henchman, not a master criminal.)

The Mansel books and some non-series works usually team Mansel with William Richard Chandos, and George Hanbury, a pair of younger men who were sent down from Oxford after beating up some Bolshies (keep in mind this is written while the Russian Revolution was still making headlines).

In the first of the thrillers, Blind Corner, Chandos and Hanbury are on the Continent when they stumble on a murder, and the dying Englishman leads them home where a clue in the collar of the dead man’s dog eventually leads to Mansel, who has the ear of the Foreign Office, Scotland Yard, the Surete, and it is suggested MI6.

Soon they are up to their necks along with their servants Carson, Bell, and Rowley (no Yates hero would go abroad without a servant in company) in battle against Count Axel the Red, and before it’s over splitting a notable treasure among themselves and the servants.

This adventure takes them to Carinthia and Castle Wagensburg, where Mansel notes with some pleasure: “If you fought a duel with a pair of Lewis guns nobody’d take the trouble to come see what it was.” (Incidentally that odd apostrophe d for “nobody would” is a typical Yates touch. He sprinkles them everywhere.)

Names play a great role in the pleasures of Yates. Among the thrillers, titles like Cost Price, She Fell Among Thieves, Red Sky at Morning, Lower than Vermin, An Eye For a Tooth, Storm Music, and Perishable Goods promise what they deliver.

Then there are the villains (rotters to a man) like Count Axel, Rose Noble, Duke Saul of Varvic, Barabbus, Casca de Palk (“the English Willie with a mouth full of teeth and an Oxford accent”), Lord Withyham, Oliver Bleeding, Erny Balch, Daniel Gedge, Douglas Bladder, Boris Blurt, Coker Falk (an American), Sycamore Tight, and Major Von Blodgenbruck among the rogues’ gallery, with helpers whose names are things like Jute Shade (a crooked private detective), Goat, Lousy, and Sweaty.

Yates is also a great one for fine place names like the Castles of Gath, Midian, and Jezeel, and estates like White Ladies, Gracidieu, Break o’ Day, Poke Abbas, and Mockery Hall. There’s even a village named Broad i’ the Beam.

Dickens’s lower middle class sentimentality probably didn’t sit well with Yates, but his character names most certainly did. He has a less than kind view of his own profession as well, with solicitors like Biretta and Cain, Aaron and Stench, and Oxen and Baal not uncommon. (It’s a wonder they ever got a client.)

Whole volumes could be written about Yates use of the English language, but it suits the novels well. Berry, warned he will get his hands dirty during a bit of second story work replies:

“That were impossible … If I massaged a goat in a coal-mine, I couldn’t get these hands dirty.”

or this from Mansel in Perishable Goods:

“But for the whistle I heard, that it was not you, Chandos, would never have entered my mind.”

and:

“Rose Noble may have a fine hand, but he knows us too well to sleep sound when we are out of his ken.”

and something must be said of Jonah’ highhandedness as in The House That Berry Built, when he has done for the wretch Stapely:

“An unknown man is found dead, We can do for the details later, don’t you agree, Falcon? (Superintendent Falcon of the Yard)”

Philo Vance or Sherlock Holmes could hardly have done it better. Falcon, naturally, agrees. Only villains ever balk at Jonah’s commands, and they usually end badly.

Where women play little role in the novels of Sapper or Buchan, they are important in Yates world. Phyllis Drummond largely exists to be kidnapped in Sapper’s (H.C. McNeile) Bulldog Drummond books and Irma Peterson mostly to do the kidnapping and seek revenge for the death of her beloved Carl.

Buchan’s women tended to be practical and boyish, but not particularly attractive, though Janet Roylance in John McNab and Kore Arabin in The Dancing Floor have their moments.

This isn’t to suggest Yates is a proto-feminist, but the ladies who occupy his books are smart and attractive and well worth the risks involved rescuing them. There’s even a hint of sex that raises its head in Yates such as when Mansel has John Bagot and Audrey Nuenham registered as man and wife in French hotels while on the run after Bagot has already had to strip her unconscious form and rub her down after a near drowning.

Or take Storm Music where the hero and heroine take refuge in an idyllic woodland cabin, take time out for a skinny dip in a remote forest glade, and spend the night together during a magnificent thunderstorm. Nothing is ever stated, but there is a good deal implied, or inferred by the reader. And the ladies often set their sights for Chandos or Mansel, though in Mansel’s case to no use.

And there is no shortage of deadly traps in the books. Castle walls must be laid siege to, and some very nasty dungeons escaped. In Red Sky at Morning a remote schloss has a treacherous Judas floor that very nearly does our heroes in (a Judas floor is one built on a pivot that when released can drop you into a nasty inescapable dungeon underneath) and the threat of ending in some cold moat or down a Jacob’s ladder ala The Prisoner of Zenda is always present.

Barzun and Taylor praised Yates for his use of “Sturm und Drang” in A Catalogue of Crime, and it’s an apt phrase, for weather and scenery and setting play a large role in the charms of the books. Storms roll across the tops of mountains, fogs hamper deadly races along treacherous roads, and natural wonders like waterfalls are always good for dispatching villains or first glimpsing a beautiful damsel. Yates took the term “blood and thunder” literally and never skimps on either. It’s almost impossible to write about Yates and not use the term full-blooded.

Like most of the heroes of the era Mansel and company are a law unto themselves, and seldom waste time with the authorities, save for a bit of cleanup at the end. They have a particular disregard for customs authorities, and Mansel’s Rolls and Aston Martin both have secret compartments used to smuggle treasure, brandy, and his sealyingham terrier, Tester past nosy customs men. (It’s been suggested that Mansel’s Aston Martin inspired James Bond’s in Goldfinger.)

The books are adventure, thrillers, not detective stories, though Yates did write one detective novel, Ne’er-Do-Well (1954) in which Superintendent Falcon relates a case to Chandos and Mansel, but Yates proves no threat to Agatha Christie. Clever puzzlers were not his forte. But most of the books, humorous and serious have criminous ties, and all are informed with an almost addictive sense of adventure as a form of play (as opposed to duty in Buchan).

Readers interested in Yates will find A.J. Smithers book Dornford Yates, A Biography and Richard Usborne’s The Clubland Heroes invaluable. Usborne’s book is perhaps the only one to really study the phenomena of Yates, Sapper, and Buchan’s ‘shockers’ and is a classic in the field. Luckily it has been reprinted often enough that it isn’t hard to find or particularly expensive when found. I have relied on it heavily in writing this since my Yates books are currently still boxed up.

For those wanting to dip their toes in, but not invest any money, several of the Berry books are available as free ebooks at Project Gutenberg and Manybooks to be read online or downloaded.

One of the short stories from Brother of Daphne was adapted as an episode of the BBC series Hannay about John Buchan’s hero Richard Hannay, and the first episode of Mystery! shown in this country was She Fell Among Thieves, with Malcolm McDowell as Chandos and Michael Jayston (Nicholas and Alexandria and Quiller) as Mansel.

There is also a musical with lyrics by Yates. Sadly the books were never adapted to film in their day, which is a shame, since they are cinematic and romantic, and the Berry books would make a wonderful television series, all done with a light touch.

Yates isn’t going to be for every taste, but if you like a bit of adventure, the romance of low-slung cars on treacherous roads at high speeds, dastardly villains, clever heroes, and worthy heroines Yates is your man. True, the term Snobbery with Violence could have been coined to describe Yates novels, but if you are very sensitive to class consciousness you probably won’t be reading much between the wars fiction anyway.

Yates is the kind of writer designed for a stormy night and a roaring fire with a cat snoring in your lap and or a good dog at your feet, even if you are really reading in bed with the television on for background noise. Reading Yates is the next best thing to a pipe and smoking jacket, and a good deal more comfortable and healthy.

But I warn you. His particular brand of the whole Clubland scene can be addictive.

Thu 14 May 2009

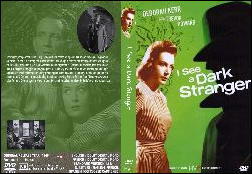

I SEE A DARK STRANGER. Individual Pictures/General Films, 1946. US title: The Adventuress. Deborah Kerr, Trevor Howard, Raymond Huntley, Norman Shelley, Garry Marsh, Tom Macaulay. Director: Frank Launder.

This one was an eye-opener, I’ll tell you that first. In spite of From Here to Eternity, I’d always thought of Deborah Kerr as being the epitome of the pleasant matronly type, even when she was too young to be a matronly type. But when she herself was young, she was a shy but determined spitfire, or at least she could play one, as her role in I See a Dark Stranger most definitely shows.

And in spite of being Scottish by birth, she could also play a young unsophisticated Irish lass so filled with hatred toward the British that when she was 21, she could travel alone to Dublin from her small village and ask to be signed up to fight them — not realizing that during World War II, Ireland was not exactly fighting the British.

You noticed the qualification in that last sentence, I’m sure. To appreciate this movie more, you’d have to know that in World War II Ireland was officially neutral, and the Nazis had somewhat realistic hopes of using the enmity between the two countries to their own ends. (See my review of The Private Wound by Nicholas Blake for a mystery novel that also uses this small but hardly insignificant bit of history as its backdrop.)

Turned down by an old comrade of her father’s in the continuance of her cause, Bridie Quilty turns to a German spy named Miller, played by Raymond Huntley with much worldly panache and aplomb, the cigarette in his mouth bobbing up and down in his mouth as he speaks as if it were alive and trying to escape.

Fatally attracted to her, however, is Lt. David Baynes (Trevor Howard), who follows her clear across England and back to Ireland, hoping to (first of all) discover why she is acting so strangely — having to dispose of a dead body in the middle of the night will do that for a girl — and then try to extricate her from the troubles she finds herself up to her pretty neck in.

Back when there was a long discussion on this blog about the definition of noir when it comes to films or books, a question was asked whether there was a satisfactory combination of noir with screwball comedy in the same movie. The Big Clock comes close (reviewed here), but here is another one.

Or at least it is if two conditions are satisfied. First of all, that there are sufficient dark and sinister elements in this film that it could be actually be called noir. It’s currently described that way on many blogs, including Steve-O’s Noir of the Week blog, but I’m not so sure. It’s borderline at best — nor do I think the comedy is of the screwball variety.

And this is where the movie went off the tracks, as far as I was concerned. The ending is pure slapstick, with pratfalls into a bathtub the highlight of all of the happy hijinks of the final reel. Till then, though, up to the point where both Bridie and Lt. Baynes are captured by German agents, it’s an exciting tale of espionage laced with humor, with the latter emphasized by Bridie’s complete wide-eyed seriousness. She’s determined to fight the British, and nothing will stop her.

Strangely enough, she doesn’t have red hair. It’s brown, and she’s young and naive, and she has blue eyes, and if nothing else, she’s a sight for sore eyes, that is for sure. The large ensemble of British movie actors and actresses behind her, a stalwart group indeed, only adds in making this a very entertaining film, noir or no. (And make that whether the ending matches the rest of the film, or not.)

Thu 14 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

WILLIAM G. TAPPLY – The Vulgar Boatman. Ballantine, paperback reprint; 1st printing, September 1989. Hardcover edition: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1987.

This is the sixth of William Tapply’s series of Brady Coyne adventures, a series that last year reached 24 in number, which is a fairly spectacular record, nor do I think he (or either of them) is going to being retiring soon. Reviewed previously on this blog have been Cutter’s Run (1998) by me, and The Dutch Blue Error (1984), a 1001 Midnights review by Kate Mattes.

Part of Tapply’s success as an author is a smooth writing style that’s just as adept in descriptive passages – sights and sounds in and around the Boston area – as it is in dialogue, which as real as it gets without having a tape recorder in your pocket.

People come to life immediately in Tapply’s hands, in other words, in just a few broad strokes at first, then some much more finely drawn ones. The way they talk and act is a great part of what makes the Brady Coyne books so entertaining and read so quickly.

In The Vulgar Boatman, Coyne is hired by a good friend who happens to be running for governor, and whose son is missing after the son’s girl friend has been found murdered. This is not good news for Tom Baron’s gubernatorial aspirations, of course. Coyne, not wishing to get drawn into politics, agrees to help, but only on a personal basis.

Both Tom’s son and the girl friend were high school students, and the easy availability of drugs, even in a small suburban town, and crack in particular, soon becomes part of the case.

I do not use the latter word to suggest that this is a detective novel, however. This is a crime novel, it’s a thriller, but a work of detective fiction, it’s not. While there are clues to follow up on, detective work is not in Brady Coyne’s arsenal of expertise.

He blunders along and stirs things up, gets into trouble himself (from several quarters) and before you know it, the book is over, more or less happily. There are, however, three separate points in the story where Coyne fails as a detective. Well, let’s call the first instance a D Minus, but the other two are F’s for sure.

I’d enumerate them in detail, but I’d have to reveal too much for the purposes of a mere review. I’d also be criticizing the book for what I’d want it to be, and not necessarily for the author’s failed intentions. Nor am I suggesting that you not read the book, as I enjoyed it anyway, and I think you might very well do so too.

« Previous Page — Next Page »