May 2009

Monthly Archive

Tue 12 May 2009

RAMONA. Biograph, 1910. Mary Pickford, Henry B. Walthall, Francis J. Grandon, Kate Bruce, W. Chrystie Miller. Based on the novel by Helen Hunt Jackson. Director: D.W. Griffith.

If cutting Crime and Punishment down to a 90 minute movie was a considerable feat, as discussed briefly here, a few posts back, then how about a 200 to 300 page novel that’s trimmed down to a very quick 17 minutes?

It can’t be done, but it was, and the result is about as good (or bad) as you might expect.

Starting with the positive, the photography is quite remarkable. But there are no dialogue cards, only brief statements of what the next scene is to display, and in the two reels, there’s only enough time to get the gist of things, no more.

Subtitled “The Story of the White Man’s Injustice to the Indian,” a Spanish girl in California (Mary Pickford) marries an Indian (Henry B. Walthall), they have a child, and as the subtitle suggests, they do not live happily ever after. The gun-toting white settlers who keep moving the small family on do not come off at all well in this movie.

This movie is to be watched for its historical significance, and — unless you tell me otherwise — for little other reason. Thankfully it still exists to be watched today, nearly 100 years later.

Tue 12 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Columns ,

ReviewsNo Comments

THE GOLDEN AGE OF BRITISH MYSTERY FICTION, PART VI

Reviews by Allen J. Hubin.

British author John Arnold perpetrated five mystery novels during the golden age of the detective story, but The London Bridge Mystery (Jenkins, 1932) is not detection at all. It’s a thriller, almost from end to end a chase story – on foot, by car, by motorcycle, in the water, instalment after instalment.

There’s very little credibility in any of it, but it is possible to get caught up in the continuous action. David Royle, an innocent accountant, is taking the underground home one evening when a girl, pursued by “toughs,” gives him a cloakroom ticket, whispers an assignation, and bolts. The toughs turn their malevolent attentions on our hero, who also takes to his heels.

Various comic and perilous episodes ensue as several groups seek the booty (fabulously valuable Chinese statuettes stolen from the British Museum). At length Royle finds someone who believes his story (an attractive and unattached young woman, would you believe?), and together they scramble for a way out of the maze, with Scotland Yard also at their heels.

Elliot Bailey, a 1930s British author never published here, wrote several novels featuring Detective Inspector Geoffrey Fraser of New Scotland Yard.

The second of these, following Death in Quiet Places, is No Crime So Great (Eldon, 1936). Here we find him wedded to Mary, whom he rescued from a killer’s clutches in the first book, and attending to a curious series of murders. Someone is taking deadly offense to England’s athletic heroes: one by one they are shot, just as the light of public acclamation shines most brightly.

They all seem without personal enemies; what twisted motive could be at work? Fraser fastens his eye on a lame newsman who seems always nearby when bodies are produced, but there are other possibilities… No Crime is typical stuff of its day, satisfactorily readable but not outstanding in narrative style or plot or unexpectedness of denouement.

They don’t come much more obscure than The Glory Box Mystery (Angus & Robertson, 1937) by G. W. Wicking. Aside from the obscurity of the author (apparently an Australian, who did indeed write other books), what’s a glory box?

It proves to be a dower chest. I gather a dower is a widow’s life portion of her husband’s lands and tenements. There’s some irony in this, for when a clerk shows the box to a prospective purchaser in Melbourne’s Home Furnishers Emporium, it contains the corpse of one of the owners.

Enter detective Dick Greenwood of the Criminal Investigation Branch. What follows is a fairly routine affair, with gradual revelation of the murderer and a final resolution that’s a bit surprising for the 1930s.

Tue 12 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Authors[2] Comments

I’ve posted several times on this blog about J. V. Turner, aka David Hume, the most recent being some biographical notes provided by Judith Gavin, whose grandfather was Turner’s brother Alfred.

Based on the information she provided, Steve Holland did some researching and has come up with a lot more, including Turner’s correct year of birth, 1905, not 1900, and that “he was, in fact, the third son and youngest of six children.”

I’m quoting here from Steve H.’s Bear Alley blog, where besides all of the biographical data he’s uncovered, he adds a complete bibliography and a few covers that I’ve not seen before.

Turner, under both his own name as and David Hume, was a thriller writer, more interested in guns and gangsters than sedate manor house detective stories. Steve also suggests that:

“Hume’s Mick Cardby novels might be the first to feature a hardboiled British private detective. Not the first British hardboiled stories: Hugh Clevely, John G. Brandon, John Hunter and Edgar Wallace had already featured gangs and gangsters in London; nor the first British private detective of which there had been countless examples; he wasn’t the first fist-swinging crime solver, either, but Mick may have been the first bonafide British private eye fighting gangs and gunmen in the UK.”

I don’t know if that’s grounds enough for you to give either Turner or Hume a try, but it is for me. I’ll soon be dipping into the small stack of their books that I’ve been accumulating for a short while now. But go read Steve’s piece. It’s worth the trip!

Tue 12 May 2009

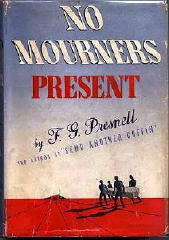

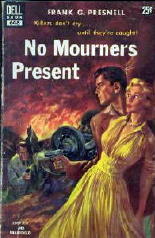

FRANK G. PRESNELL – No Mourners Present.

Dell 646, paperback reprint; no date stated, but circa 1953. (Cover by Robert Stanley.) Hardcover edition: William Morrow & Co., 1940.

The jacket of the hardcover edition suggests that the book may have been published as by “F. G. Presnell,” but any final judgment on that would have to wait until the title page has been examined, the final and only arbitrator on matters of bibliographic importance such as this.

Looking for more information about Mr. Presnell (1906-1967), I’ve not found anything on the Internet that either discusses him or his three mysteries in any way that’s significant. At the moment, all I can tell you about him personally is what Al Hubin says in Crime Fiction IV:

“Born in Mexico; educated at Antioch College and Ohio State Univ.; designer and engineer; lived in Ohio for 40 years, then in Los Angeles.”

Which is a start, but what it doesn’t say is why Mr. Presnell wrote two good books in 1939 and 1940, both with high-powered (and hard-boiled) practicing attorney John Webb, but then not another novel until 1951, and alas, Webb is not in it.

For the record, here is a list of Presnell’s only contributions to the world of crime fiction:

Send Another Coffin. Morrow, hc, 1939. Detective Book Magazine, Winter 1939-40. Handi-Book #39, pb, 1945.

No Mourners Present. Morrow, hc, 1940. Dell 646, pb, 1953.

Too Hot to Handle. M. S. Mill / Morrow, hc, 1951. Dell 593, pb, 1952.

I had not known until I looked it up, but a movie was made of Send Another Coffin, one I’ve never seen, but I believe I shall have to purchase it. The title of the movie is Slightly Dishonorable (United Artists, 1940), and besides Pat O’Brien and Ruth Terry, whom you see below, as the two leading characters – I’ll get to that in the next paragraph – Edward Arnold and Broderick Crawford are also in the film, big names both.

These photos were taken at different times, and neither time may coincide with the movie, but they will give you an idea at least of what Hollywood thought the characters looked like. (Since I was reading the Dell paperback, you can tell what I thought they looked like, when I was reading it. The scene on the cover, which you’ll see somewhere below, is in the book.)

In the movie, Ruth Terry is credited only as “Night Club Singer,” but in the book she has a name: Anne Seymour. In the followup book, the one at hand, she has a brand new name, that of Anne Webb. A substantial part of No Mourners Present is the mystery novel, of course – and I’ll get to that in moment too – but another significant portion of it, one mixed up one with the other, concerns the domestic life of the two newlyweds.

As it happens, the tough attorney John Webb is deeply in love with his wife. That much is apparent right away. He also seems to wonder how it is that he is so lucky to have her in love with him. Her background as a singer seems to be a concern to him as well: how well will she fit in with the wealthy set that he sometimes hangs around with?

Without revealing too much, I think Anne Webb is smarter in many ways than he thinks she is, and that she can hold her own in his world very well indeed, and maybe even better. John has nothing to worry about in that regard.

Of course there is no way of knowing. Two books with the Webbs, and that was all there were. As for Mr. Presnell, perhaps we must assume that the war intervened, and life and a family and earning a living.

The town in which John Webb as an attorney also has considerable political clout is not named, I don’t believe, and since Hubin doesn’t suggest a setting (I just checked) neither do I believe it is a matter of my missing it.

With very few preliminaries, the mystery gets into action right away, with Jake Barman’s murder taking place on page 15, one page after Webb very nearly slugs a radio news commentator for a remark he makes about Anne. Anne takes him to task reproachfully afterward. “Listen,” she says. “You’ve got to stop hitting people.”

This fellow Barman is a partner in a building firm, or he was, and he also had ambitions of being elected governor. He is on the outs with his wife, however, which is a liability, especially since everyone knows that Julie Gilson, his secretary, is also his mistress. She’s also the leading suspect as well, especially after she disappears completely from sight after Barman’s death.

Without a client, Webb is only incidentally involved until Julie’s brother comes to town are hires him to help protect her name. Once hired, Webb goes immediately into Perry Mason mode. See page 40, and you will see exactly what I mean.

If you’re only in your 30s or 40s, it may not realize it – it’s probably too long ago – but in 1940 if your company bucked either the gangs or the unions, people were maimed for life. This is the sort of thing that gets Webb’s blood boiling as well. Here’s a long quote from page 45. He’s talking to the man he’s working for in charge of operations at a chain of cleaning establishments.

“… In the second place, even if I didn’t give a good Goddamn whether Acme ever makes another nickel or not, I’ve got a front to keep up. Why do you think people pay me fancy prices to do things for them? Because they think I’m going to lie down and let myself be walked on? Like hell they do! They hire me because they know they’ll get grade-A effort, anyhow. And how come I usually give them results besides? Because the other side knows they’ll sweat for anything they get. […] If anybody from this damn cleaning-and-dyeing-trades racket comes around here, you tell ’em to talk to me.”

I mentioned Perry Mason a short while back. Perry was tough in his early days, but not as tough as John Webb. Here is a portions of his thoughts, his philosophy of action, you might say, taken from page 61:

Cabash was tough and vicious, but he wasn’t smart. He’d start trying to bluff us, and when he did, it was up to me to give him a chance to do nothing but wonder what hit him. I didn’t know how I was going to work it, but you can always figure out ways if you’re willing to use them.

As a word of warning, the book is a little too talky to be this tough all the way through, but when it is, it is. It earns high points as a detective novel as well, or at least it did with me, with plenty of twists and turns in the plot to keep Webb’s brain (and mine) working in as finely-tuned a fashion as his brawn.

The solution is not nearly as finely worked out as one of Perry Mason’s, though, containing as it does one small gap I haven’t quite yet figured out.

Nonetheless, even if the mystery itself is not a classic that anyone will remember for very long, if there’s any in mourning at the moment, it’s me, wishing that there were a next one to read, and as much for the characters, I would advise you, as for anything else. Sadly to say, one more time, there wasn’t a next one to read at the time, and there isn’t now.

Sun 10 May 2009

BORDERTOWN. Warner Brothers, 1935. Paul Muni, Bette Davis, Margaret Lindsay, Eugene Pallette, Robert Barrat, Soledad Jiménez. Suggested by the book Border Town, by Carroll Graham. Director: Archie Mayo.

This was recently shown as part of TCM’s Latino Festival that’s been going on all month long, and if I may say so, there’s something of mixed message made by this movie. The focus of the films in this series is how Latinos, in this case Mexican-Americans, have been portrayed on the screen.

How it works out in this case, I’ll get back to — with a small CAVEAT that more of the story line is going to be hinted at, if not revealed, than is customarily done on this blog.

Paul Muni, who was Jewish and a Hollywood superstar in the 1930s, plays Johnny Ramirez in Bordertown, a young resident of Los Angeles’s Mexican Quarter who after five years of hard work, earns his law degree from a small but apparently reputable night school. As in Crime and Punishment, reviewed here not too long ago, the opening scenes are of the graduating ceremony.

And as with Raskolnikov in that other film, getting a degree is not the same thing as making a success of yourself. Johnny’s first appearance in court is a disaster. Summarily disbarred, he heads for Mexico and in a town just south of the border where he works his way up from a night club bouncer to a 25% partnership.

And where the boss’s wife (a blonde and coolly calculating Bette Davis) has eyes for him, which is where the noir aspects kick in. Luckily for Johnny, he is unaware of what you’ve already probably gathered happens next.

His eyes are instead on Dale Elwell, the female socialite who was on the other side of his one and only courtroom case (Margaret Lindsay), but who comes slumming down to see Johnny’s new casino, built with you-know-who’s money.

As I warned you earlier, I’ve already told you more of the plot that I should and normally would, but I think in this case, no matter how little I told, you’d fill in much of the details on your own anyway – and besides, you need the Big Picture.

The black-and-white photography is fine — even in the silent era, cameramen at the major studios really knew their business — but as for the story itself, there is not a subtle line or scene in this movie. Once started, you will have the continual feeling that you know what exactly will happen next, and it does.

Not that that’s a real complaint. I enjoy stories with romantic — and deadly — triangles like this, and if they hadn’t been filmed many times before this movie was made, they’ve certainly been made many times since.

So, except for the ending, I enjoyed this film. In terms of Latino images, there’s nothing too preachy about the injustices that poorer Mexican-Americans faced in a elite world of wealthy WASPs in the 20s and 30s, or at least I didn’t find it so, but the ending? It can take the wind right out of your sails. It took quite a few more years, apparently, before interracial romances would be deemed fitting and proper subject matter for movie viewers to see.

Whatever message may have been intended before the final scene, if there was one, is quickly whisked away, and very nearly without a trace.

PostScript. I’ve just discovered an almost three minute trailer for the film on the Amazon page offering the DVD for sale. I suspect that you hunt around, you may find more of the movie available online. Check YouTube and similar sites.

Sun 10 May 2009

LAWRENCE BLOCK – The Specialists.

Foul Play Press, paperback reprint, 1985. First published as Gold Medal R2067: paperback original, 1969. Other reprint editions: Carroll & Graf, pb, 1993; James Cahill Publishing, Aliso Viejo, California, hc, 1996.

Most of Block’s early crime thrillers, including the Tanner series, were paperbacks, almost all from Gold Medal. The first Matt Scudder book was published by Dell in 1976, and although Scudder’s career is still going today, and in hardcover, Block’s own writing career didn’t take off until 1977, when the first “Burglar” book came out in hardcover (Burglars Can’t Be Choosers, Random House).

Which places The Specialists toward the end of the first stage of Block’s career, before he seems to have gone on a 4 or 5 year hiatus. While the book starts out sounding like a winner, its plot soon begins to hold together like a pile of yesterday’s oatmeal.

Picture a group of returned Vietnam war veterans who decide to continue their commando tactics against the forces of crime and corruption. From page 26: “All over the country there were dirty men with dirty money, men the law could never get close to, but once you took their money away, it turned clean.”

Villain: a New Jersey gangster who’s been laundering his ill-gotten gains by owning banks, and then robbing them (or at least one of them) for additional profit.

Problem: the good guys play as nasty as the bad guys. There’s no one to root for. Which may have been Block’s idea all along — it’s certainly a valid approach to a crime story — but while there are flashes of good characterization and even better side commentaries about the state of the world, there’s nothing here that even hints at the idea of subtlety.

— March 2003

[UPDATE] 05-10-09. This brief review does not mention the many books that Block wrote under pen names, nor any of the “sleazy” paperback originals he wrote early on his career, many of them having criminous content. Some of the latter have been resurrected within the last year or so by Hard Card Crime. See my review of Lucky at Cards as a prime example.

At the moment I cannot account for how negative this review was, and it was written only six years ago. The book really may be as bad I said it was, but reading my comments now, they wouldn’t persuade me against giving it another try.

If you’re a Lawrence Block fan but haven’t read the book yet, please do so, and let me know how wrong I was, if I was. (This statement also applies, of course, if you’ve already read the book.)

Other books by Lawrence Block which have been reviewed on this blog: Mona (1961), by me; and The Girl with the Long Green Heart (1965), by Ted Fitzgerald.

Sun 10 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

MICHAEL INNES – The Daffodil Affair.

Victor Gollancz, UK, hardcover 1942. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1942. Reprinted several times, including the following: Berkley F925, June 1964; Penguin, several editions, both in the UK and the US.

You might want to go back and read my review of Innes’s Seven Suspects first, as I’m going to go out on a limb here, and say that that book is a lot more representative of both Michael Innes and Inspector John Appleby than The Daffodil Affair is, and by a long shot — by factor of, in fact, say several thousand times or so.

I have to stop and tell you the truth right here, before going on any farther. I have never read a mystery or detective story that is ANYTHING like this one. In terms of being unique, this one’s the ultimate in uniqueness.

Have I intrigued you? I hope not, because my intention at this point is NOT to convince you to read this book. I don’t intend to have you NOT read it either. You do need to know, perhaps, what’s in store for you if you read this book, and well, I’ll do my best.

I’ll start, though, with a long passage from page 89 of the Penguin edition. The setting is both heading down a river [the Amazon?] to a secret encampment where a man named Wine is making a collection of animals, people and even inanimate objects with psychic powers:

The night was dark, and Appleby blinked into it. Hudspith [Appleby’s colleague, also from Scotland Yard] bubbling with the raffish idiom of the nineteen hundreds was a mildly surprising phenomenon. But then, so, and in an equally dated away, were a calculating horse [named Daffodil] and an Italian medium specializing in materializations.

A witch and a girl possesed by demons [named Lucy, her demons being her multiple personalities] were exhibits more ‘period’ still.

In fact — said Appleby to himself as he paced the blacked-out deck once more — this ship has the nineteen-forties dead astern and is heading for the past at its full economic speed of eighteen knots. The Time Ship: master, Emery Wine [the man who has kidnapped all of the above, all with psychic abilities, not including Appleby and Hudspith]. It sounded like H. G. Wells… He took several turns about the deck and returned to the smoke-room.

Hudspith’s voice greeted him as he entered. […]

Hudspith, though still talking defiantly, was looking at the silent Wine and Beaglehole [Wine’s assistant in crime] with an occasional furtive sideways glance — as a man may do who is presently going to realize that he has been making a fool of himself. ‘There was a girl in London,’ said Hudspith, raising his voice with a sort of desperate and fading arrogance. ‘Just a few months ago. Lucy, her name was…’

Rather abruptly Appleby plumped down on a settee. Perhaps he had been dull. Certainly he had not realized it was all heading for this.

The book, written during the darkest days of World War II, is perhaps (I am not quite sure) a reaction to Science, which had at that time nearly brought England to its knees — very dark days indeed. Can the uncanny also move the world? Wine soon intends to try.

Here’s another long quote, this time from page 177. Appleby and Hudspith are essentially prisoners somewhere on an island in South America. Hudspith speaks first. (I’ll leave out one key, essential part, but I think you may find the rest amusing)

‘How many people would you say have written detective stories?’

Appleby yawned. ‘Hundreds, I should imagine.’

‘Quite so – and some of them have written scores of books. Folk with intelligences ranging from moderate through good to excellent. A couple of women are quite excellent; there’s no other word for them.’

‘Is that so? I say, Hudspith, it must be deuced late.’

‘And, what would you say those hundreds of folk are constantly after?’

‘Money.’ Appleby’s voice, if sleepy, was decided.

‘They’re constantly after a really original motive for murder. And here one is. […] It’s a genuinely new motive, and none of them has ever thought of it.’

‘Probably someone has. You just haven’t read that particular yarn. Good night.’

‘But I haven’t explained what I mean. About waste that is.’ Hudspith’s voice continued to come laboriously out of the night. ‘Here is a perfect detective-story motive, and yet we’re not in a detective story at all.’

‘My dear man, you’re talking like something in Pirandello. Go to sleep.’

‘We’re in a sort of hodge-podge of fantasy and harumscarum adventure that isn’t a proper detective story at all. We might be by Michael Innes.’

‘Innes? I’ve never heard of him.’ Appleby spoke with decided exasperation. ‘You might employ your last hours more profitably than in chatter about the underworld of letters. Go to sleep. Go to sleep and dream of the nice boiled egg they send to the condemned cell on the fatal morning.’

Hudspith sighed and for a time was silent. ‘It’s all very well rotting,’ he said at length. ‘But about this idea of Lucy’s — do you think it will work?’

Silence answered him.

Bear with me. Here’s the last of the quoting I’ll be doing. I’ll also let it be the end of this review. If at the end you still want to read the book, I’ll allow you, but keep in mind, the decision is yours. This passage comes from page 43, when Daffodil was still a key component of the story. Appleby has found Mr Gee at the livery stable from which the horse has been stolen:

‘Mr Gee,’ he parried, did it never occur to you that these peculiar powers made Daffodil an unusually valuable horse? Imagine the thing in a circus. Members of the audience are invited to come up, hold Daffodil by the bridle and think of a number. And then Daffodil taps it out. The trick would make any showman’s fortune.’

‘It so happens,’ said Mr Gee with dignity, that I’m not a showman. But if Daffodil is valuable the way you suggest, then you know something about them in whose hands he was before. They weren’t show people, or they wouldn’t have let him go.’

Appleby got up. ‘Mr Gee, you ought to have taken to my profession.’

There’s compliments you can return,’ said Mr Gee, ‘and there’s compliments you can’t.’

Sat 9 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Authors ,

ReviewsNo Comments

JAN ROFFMAN – One Wreath with Love. Doubleday Crime Club, US, hardcover, 1978. Robert Hale, UK, hardcover, 1979. No paperback edition.

Jan Roffman has written nearly a dozen mystery novels by now, so it’s be exceedingly presumptuous of me to try to generalize anything about her writing from a sample of size only one, but (as I’m often resigned into doing) I will anyway:

On the basis of this book, she has a tendency to overwrite, even badly, especially in the early chapters, but in the process of doing so, she creates a good many characters whose lives are as ingeniously intertwined as they are in the best of soap opera tragedy.

I’m pleased to report that the overwriting begins to disappear as the characters become more familiar, or so it seems, and by the end, tears will come close to falling. Murder is involved, but we know who did it in chapter one, in which a particularly repugnant death scene is used to build an almost watertight alibi.

Many of the characters in this book are afflicted with various stages of senility or insanity, and maybe that’s what I mistook for overwriting. Roffman is clearly adept in creating people out of touch with reality. The contrast is at its most effective when an under-disciplined seven-year-old named Tilly makes a friend of the dottering old lady who may have caught sight of the killer.

There’s also the rapidly failing mind of the ex-wife with a not-so-reliable ghost haunting her, and so in turn Chief Superintendent Deacon is annoyed.

This is not a detective story, but all the same, I think it can easily get under your skin.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 3, May-June 1979, mildly revised.

Bio-bibliographic data —

Jan Roffman was a pen name of Margaret Summerton, who died in 1979, according to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, but that’s about all the personal information I have about her. Even though the US edition of One Wreath with Love was published before the one in the UK, I’m sure she was British.

Under her own name, Summerton wrote 14 novels, with 10 of them also appearing in the US in hardcover. When they were reprinted here in paperback, usually by Ace, they were invariably marketed as gothic romances. The Sea House, the cover of which is shown below, is a prime example.

She also wrote at least 10 books as by Jan Roffman. I can’t give you an exact count, because two books published under that byline in the US have as yet not been matched up with their UK counterparts — and it’s possible there aren’t any.

One Wreath with Love was not published in paperback, but other Roffman books were, and once again, the marketing division at Ace assumed that they would sell best as gothics. They were probably right. Shown is the cover of The Reflection of Evil, aka Death of a Fox (US) and Winter of the Fox (UK).

Sat 9 May 2009

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT. Columbia, 1935. Peter Lorre, Edward Arnold, Marian Marsh, Tala Birell, Elisabeth Risdon, Robert Allen, Douglass Dumbrille, Gene Lockhart, Mrs. Patrick Campbell. Based on the novel by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Director: Josef von Sternberg.

To begin with, the novel’s 600 to 800 pages long, depending on the size of font used and how wide the margins are. If a film adaptation is only 90 minutes long, as is this US version done in 1935, answer yourself this: how much of the book could be crammed in?

So, OK, let’s let that go, and talk about the movie as a movie. It was one of the earliest films that Peter Lorre made in the US, and as a leading man yet, in the role of criminology student Roderick Raskolnikov, who commits a murder and almost, but not quite, gets away with it.

Dogging his trail is Edward Arnold, as Inspector Porfiry Petrovich, not necessarily following the academic approach espoused by Raskolnikov, who as it becomes clear, is a rival in more ways than one.

In spite of first appearances, Porfiry is gradually seen as a student of human nature, allowing his prey to alternate between arrogance and fear by using only one simple method: by allowing him to remain free — and thereby trapping and convicting himself by his own hand.

A role that was meant to be played by Peter Lorre, perhaps, who does both arrogance and fear very well, and yet, in Crime and Punishment, he shows he has a human side as well, committing the murder of the miserly lady pawnbroker (Mrs. Patrick Campbell) yes, but giving the young streetwalker Sonya (a radiant Marian Marsh) all of the money given him earlier in return for pawning his father’s watch. (It is interesting to note how Sonya’s means of earning a living manages to be very conveniently skipped over.)

The film came along far too early to be classified correctly as noir, perhaps, but there are a number of elements that could easily make it fit (one might argue) into the category.

Not only the story itself, with Raskolnikov continually finding himself sliding into the abyss of his own mind — a quiet kind of desperation — but the black-and-white photography is also quite magnificent, showing the better parts of the unknown city (Moscow?) where the story takes place, as well as some of the worse, including Raskolnikov’s rather squalid apartment, for which, in spite of his brilliance, he cannot even pay the rent.

So, my final comment and overall impression? A very entertaining film, a movie that when I started, I intended to see only the first ten minutes as a preview, but which I forgot myself and watched all the way through to the end instead.

Fri 8 May 2009

JANE HADDAM – Cheating at Solitaire. St. Martin’s, paperback reprint; 1st printing, April 2009. Hardcover edition: St. Martin’s, April 2008

Upstairs as I’m typing this, I don’t have access to the Internet, so I don’t know how many books Jane Haddam has written in her series of ex-FBI agent Gregor Demarkian’s cases, but there have been quite a few of them. (According to Amazon.com, as I’ve discovered later, this is the 22nd.)

I wish that I’ve read more of them — only one before this one — and that’s because of the question I’ve been trying to answer. I’m not trying to diminish Demarkian’s popularity by a single whit, but the strange thing is that I can’t quite explain why it is that he’s had the career he has.

Are the books what are commonly referred to in the vernacular as cozies? Not really, although some of early parts of this particular adventure takes place in Demarkian’s boyhood Armenian neighborhood in Philadelphia (Cavanaugh Street) where his marriage to his long-time lover Bennis Hannaford is soon to take place. Check this off. Roots are important. Long time friends are important.

But neither of the latter two items have anything to do with the case that Demarkian is called in on in Cheating at Solitaire, a fact for which I (admittedly) felt uncomfortably grateful, as the atmosphere felt a little too close for me. I suspect, however, that long time fans of the series might wish there were more!

Dead is one of the crew of a film being made in Margaret’s Harbor, found shot to death in his car in a New England style Nor’easter on New Year’s Eve. The local police force, and very few in number, have chosen the most likely suspect, not realizing that (in Demarkian’s quick analysis of the case) simply do not add up. The bullet has not been found where it should be, and where the victim’s blood is found on the person arrested does not match the local authorities’ version of the events. (See page 135.)

You might therefore check off great detective work as being part of the appeal, but Demarkian’s rebuttal of the prosecution’s facts is far from a work of genius. Anyone willing to let the facts guide the theory, rather than the other way around, could have done as well.

Well before the end of the tale Demarkian also suggests that he knows who did it, too the surprise and amazement of all, but he later backs off suggesting that the he only knows the kind of person capable of doing it. By the story’s end, nor in the final wrapup, is his earlier claim mentioned.

This may sound as though I was greatly disappointed in the mystery and how it develops and in the solution. No, not really. Only mildly. I do think, however, that Demarkian’s detective skills are more talked about than shown.

I have not mentioned, though, what this book is really about. In paperback the book is 388 pages long, which is far too long for the small amount of detective work that’s involved to be a major reason for its popularity.

What the book is really about is a certain disdain for the existence of popular culture creatures such as Paris Hilton, Anna Nicole Smith and Brittany Spears. Three such women, key players in this book — two from out of town, one local and not exempt from the author’s indictment — reflect the same shallow values, at least outwardly. (A surprise or two may be in store here.)

But by shallow values, I mean vapid, stupid behavior, including such actions as getting drunk in local bars and running about town in skimpy clothing and a noticeable lack of underwear. Not that they’re the only culprits and targets of Jane Haddam’s wrath. This book also includes one of the most vicious attacks by a gang of paparazzi on an extremely vulnerable celebrity that you will read anywhere, a statement that’s almost guaranteed.

Time and time again the book stops while some rather effective moralizing takes place, sometimes in the minds of the players, sometimes as a general authorial voice. Such commentary on the modern world, if not modern society as a whole — or should that be the other way around? — is difficult to disagree with, but after a while it becomes as overbearing as the close-knit neighborhood that produced Gregor Demarkian into the world, along with his values.

But do check off values. As overdone as the promotion may be, values are the key to Cheating at Soltaire — hometown values, small town values, I don’t believe it matters either way. Maybe they’re even universal values and and maybe this is why readers keep coming back for more.

« Previous Page — Next Page »